He used to carry his guitar in a gunnysack

Go sit beneath the tree by the railroad track

Oh, the engineer would see him sittin’ in the shade

Strummin’ with the rhythm that the drivers made

—“Johnny B. Goode”

If scientists were to examine “Johnny B. Goode,” Chuck Berry’s 1958 hit song from which those semiautobiographical couplets are snatched, on the subatomic level, they would no doubt issue a scholarly study proving it to be the purest distillation of rock and roll to ever catch a jukebox on fire. Not far behind would be “Back in the U.S.A.,” “Memphis, Tennessee,” and “Roll Over Beethoven”—a musical legacy that has been extolled far and wide since the singer’s death in March, and will continue this month with the release of his first studio album since 1979, Chuck.

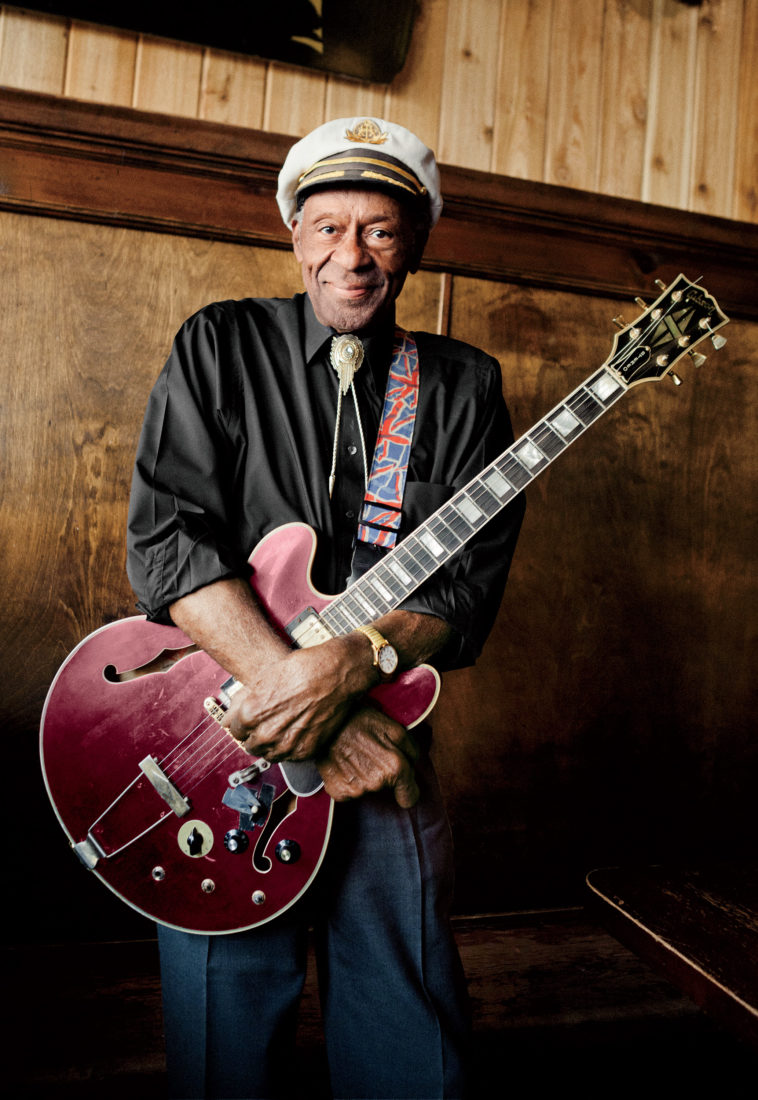

Photo: Danny Clinch

Berry had an affinity for Cadillacs (like this 1959 model), featuring one in his first hit song, “Maybellene.”

Born in St. Louis to a family that came from Kentucky, where two of his great-grandparents had been enslaved, Berry oozed a knack for wordplay and country-meets-R&B guitar riffs that put him at ground zero for that rebellious new sound all the teenagers were digging in the fifties. Indeed, many consider his “Maybellene” the first true rock-and-roll song. He was no slacker in the showmanship department, either, picking guitar while executing the splits or his trademark “duckwalk” across the stage. At a time when much of America was still segregated, his electric style crossed racial divides and won him a wide-ranging legion of fans, from country star Marty Stuart to fellow pioneer Little Richard—proof that his songs transcended genre. That’s not to say Berry wasn’t flawed; over the years, instances of bad behavior, including an armed-robbery conviction and a bathroom videotaping scandal, tarnished his near-deity status.

Berry performed well into his eighties, often showing up to a club without backing musicians because the promoter could just hire a local band that would, naturally, already know all his songs. Before his death, he had been working on the new album. Set to be released June 16, Chuck is populated with unapologetically throwback melodies and collaborations with young disciples such as Nathaniel Rateliff. Here’s what Rateliff and a few other admirers have to say about Berry’s indelible influence.

“I grew up hearing stories about my parents, aunts and uncles, and their friends hanging out at ‘Chuck’s club’ in St. Louis. At the time, I didn’t realize that it was the same brown-eyed handsome man who I loved listening to. The same person who had influenced the Rolling Stones and the Beatles. Or as I like to think of him: the King of Rock and Roll.”

—Nathaniel Rateliff, singer-songwriter

“Chuck Berry’s music broke my sound barrier. His songs liberated me from the jump-rope nursery-rhyme jingles of childhood and made me hungry for real-life music. I recall the day I heard ‘Memphis, Tennessee.’ From that moment, I knew all the best songs tell a story. All great songs carry a message. My revelation wasn’t gleaned, because Chuck told me: My uncle took the message and he wrote it on the wall.”

—Robert Earl Keen, singer-songwriter

“He was really at the epicenter of the crossover from R&B to rock and roll. We think about Elvis Presley, but [Berry] wrote

the songs—he didn’t just sing the songs. He’s kind of like the poster boy for the appropriation of African American music:

His song then becomes somebody else’s song, who then makes a megahit out of it. Like the Beach Boys’ ‘Surfin’ U.S.A.’ used the melody of Berry’s ‘Sweet Little Sixteen.’ But he was mega-multitalented. What he represents is resistance to a kind of pigeonholing. It’s survival.”

—Jessica B. Harris, culture and food historian

“Chuck Berry and Thomas Edison—neck and neck in regard to impact.”

—Delbert McClinton, singer-songwriter

“I have a poster from a 2009 concert in New Orleans where Fats Domino was [honored]. The complete lineup reads: B. B. King, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Wyclef Jean, Taj Mahal, Keb’ Mo’, Junior Brown, Ozomatli. Quite a show! It was my last chance to experience Chuck Berry, who didn’t just ‘rock’; his songwriting had a lot of storytelling, much like country music. He was truly one of a kind.”

—Junior Brown, singer-songwriter and guitarist

“I covered ‘No Particular Place to Go’ when I played Bonnaroo, and I thought a lot about his performance. He was a very charismatic performer, but not necessarily trying to be too showy or too perfect—that’s inspiring to me as an artist, to see someone get up there and try to just be into the music they’re playing. People always say, ‘Oh, music’s gotten really bad now. Can’t get much worse than it is now.’ What they don’t realize is that there’s bad music in every decade—or, there’s just that sameness in every decade. The out-

liers are the people who are doing something a little different, or a little ahead of their time [as Berry did]. If you’re doing

that, you’re bound to stand out—to stand the test of time.”

—Aubrie Sellers, singer-songwriter