Not only does Matthew McConaughey have his feet firmly planted in the South—he, his wife, Camila Alves, and their three children split time between Austin, Texas, where they have a home, and New Orleans, where they stay for long stretches while the actor is filming in the area—but he’s also kicked off a career transformation portraying Southern characters. In 2012, he played the title role in Mud, a film set in Arkansas about a fugitive in delusional pursuit of an unattainable woman. It was dark, complex, and intense—a hint of things to come. In Dallas Buyers Club (2013), McConaughey immersed himself in the city’s AIDS-afflicted gay subculture, and in the first season of the HBO series True Detective, in 2014, he tromped through the underbelly of rural Louisiana. The former won him an Oscar and a Golden Globe, and the latter garnered Emmy and Globe nominations, cementing his status as one of Hollywood’s most compelling dramatic forces. In his latest film, the highly anticipated Free State of Jones, due to hit theaters in May, the actor takes on yet another Southern persona—the renegade Newton Knight, a real-life Mississippian who rebelled against the Confederate army. We caught up with McConaughey in New Orleans, just as he was finishing up filming that project, to discuss storytelling, Reconstruction, and the beauty of potholes.

You keep coming back to New Orleans. Why?

One, there’s a great tax break to make films here. [Laughs.] But really, it’s at the top of my list of shooting locations. My dad’s from around here, Morgan City. When I was a kid living in Texas, we used to come back for the blessing of the fleet before they would go out shrimping. So New Orleans is sort of romantic in my mind. Being here as an adult, with my own family, and finding the Garden District, instead of just the Quarter, has been a revelation. When I’m working here, we put the kids in school, rent a house, bring the dogs, the cat, the whole deal. We love it here, man.

What kind of dogs?

We’ve got two heeler mixes and a dachshund mix—Breezy, Suzy, and Cheesy.

You identify as a Southerner, but your pedigree isn’t purely Southern, is it?

Nope. My mom’s from Trenton, New Jersey. My dad was born in Jackson, Mississippi, and raised in Morgan City. They met at the University of Kentucky, where my dad played football under Bear Bryant. Dad and Bear didn’t get along, because Bear didn’t play him in the Orange Bowl or something like that, so my father transferred to the University of Houston. The summer before he started there, he went back to his mom’s house in Morgan City. When he got there, my mom—his girlfriend and not-yet-fiancée—answered the door. She said, ‘I’m going to fast-forward this situation,’ and handed him an invitation to their wedding. ‘You’ve got twenty-four hours,’ she said. ‘I’ll need a yes or a no.’

That’s bold.

Well, that’s my mom.

Your father wasn’t exactly a pushover, was he?

Not at all! After he left college, he was drafted by the Green Bay Packers. He played just one year. I asked him, ‘How did you know it was over?’ He said, ‘I was returning a punt, and I got hit. I was lying on my back. And when I looked down, I saw the bottom of my foot and my toe was facing my chest.’ That was pretty much it.

Obviously, football is huge in Longview, Texas, where you grew up. Did you play?

A bit. But Dad never pushed us into it. I mean, we played—I’ve got two older brothers—but I wasn’t fast enough or big enough, and I barely had any peach fuzz going into the ninth grade. I remember being really nervous when I went to him to say, ‘Dad, I’m not sure I want to play football anymore.’ And he went, ‘Great. That’s great.’ I said, ‘I’d really rather play golf.’ He said, ‘Good—you can play that till you go down.’ I said, ‘You’re sure you’re fine with that?’ He said, ‘Let me ask you a question. When I’m walking toward your room, do you know it’s me before I get there?’ I said, ‘Yeah, because I can hear you.’ He said, ‘What do you hear?’ And I went, ‘Pop-pip. Pop-pip. I hear your bones poppin’ down the hallway.’ He said, ‘Right. I’ve got a metal plate in my back and pins in my knee and ankle. You don’t have to play if you don’t want to play.’

Photo: Nigel Parry

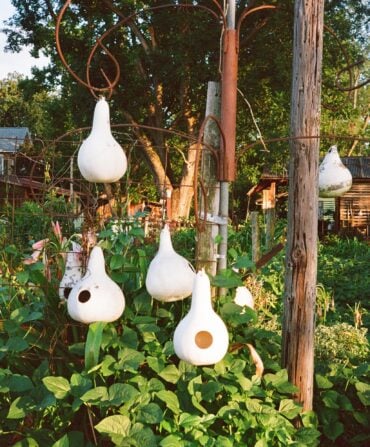

Kicking Back

McConaughey, photographed in New Orleans’ Garden District. Shirt by Frank & Oak. Jeans by Dolce & Gabbana. Watch by Omega. Shoes by Coach.

So you became a fairly serious golfer instead.

I got down to a four handicap. I played for Longview High School, and then played some intramural golf. I was reminded recently that I won an intramural tournament.

Do you still play?

Not really. We had a fund-raiser recently in Austin, and it was the first time I’d picked up a club in a year. I’ve got three kids now. I have to pick out my hour or so a day to go break a sweat, and I haven’t chosen golf.

Speaking of your busy schedule, tell me about your latest film. What attracted you to The Free State of Jones?

I’m not much of a Civil War buff. I’ve always thought that when the Civil War is put on film, it’s not very dynamic. But in Free State of Jones, the action is killer. At the same time, it’s an incredibly intimate story about a real revolutionary at that time, Newt Knight. The other thing that [the writer-director] Gary Ross tackles is Reconstruction. The civil rights movement in the sixties really started what we collectively think happened at the end of the Civil War. Back then, things kind of went back to the way they were: Swear your oath to the Union, get your plantation and people back, and life goes on. But Reconstruction is still going on. The end of this movie is very relevant today. I went into this thinking this is a Civil War piece; it has its place and time. But I learned differently. This is a vibrant, alive story about a man people know not much about.

Newt Knight was a complicated guy, wasn’t he?

Actually, I think, he was very simple. I mean, simple in that in everything he did, he never measured the consequences. It was all based on, Well, that’s just not right. No man should be wearing an iron collar around his neck. I’m going to take that off of him. He moved from there. In a lot of ways, he was ahead of his time. He was a revolutionary but he was also a pirate, and a real pain in the Confederate army’s ass.

The turn in your career—were you seeking a transition?

I was conscious of it to a degree. When you’re growing up, you make choices not necessarily by what you want to do, but by eliminating what you don’t want to do. And then you grow up, you mature, and you become aware of what you want. You choose those things and you go after those things, whether it’s a woman, a job, you name it. The career change goes back to the process of elimination. I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do. I knew what I didn’t want to do. I asked myself, Are you ready, Matthew? And I spoke a lot to my wife about this too, of course—if you say no to a lot of the things you’ve been saying yes to, it’s probably going to get dry for a little while. Are you ready to go without work for however long? I was starting a family—that was first on my mind. I had a new job, being a father. I love that and it kept me sane, because I love to work. And I said no to a lot of roles. It took about eighteen months for Hollywood to really get the message.

You’re playing a lot of Southern characters these days. Is that deliberate?

Well, I never really looked at it like playing a Southern role was going against the grain. I also never chose a role because I said, ‘Hey, this is a Southern character.’ I always looked at it as ‘This is a great character who happens to be from the South.’ I’m comfortable in nature. I like people. I love the spoken word. Have these guys I’ve played been storytellers? Yeah, Mud sure was. I’m not specifically trying to ‘play Southern.’ It just so happens that some of the greatest characters are from the South. Think of the chefs that have come out of the South. Think of the music, athletes, food. There’s a musicality to the speech of the South that I love.

What movies really get it right about the South?

You’re going to have to help me there. I’m not much of a movie buff. I mean, I like making them much more than I like watching them. I didn’t see my first film until I was about seventeen. But about the Southern movie—you sure can tell when someone decides to play the stereotype. That can be good for a comedy, I guess. Part of the stereotype is that we’re slow. I like to say that we take our time. Look at New Orleans. Part of me hopes that they don’t fix the potholes. In the South, it’s actually built in—you have to take your time. As for the roads in New Orleans, you go too fast, and you’ll burn your lap with coffee and your shocks will be gone. You know what I mean? Just take your time.

What else about New Orleans do you like?

Quirky stuff, hometown stuff. I go to a gym that’s on the honor system. Guy gives you a code, gym’s open 24-7, you go in. I ask the guy, ‘What do I owe you?’ Guy says, ‘Before you leave town, just let me know how many days you worked out.’ It’s such a great town. People are engaged with one another. They’re happy to see you, and you them. And there’s no place you get over a hangover quicker. Tuesday morning, they’re like, ‘It’s almost the weekend.’ I really got attached to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. I was sitting at home in Malibu, watching what was happening here on TV, and I said, I’ve got to go there and do something. There were a thousand things that needed to be done. But what I did was I went over to this local animal hospital, and there was a guy, a doctor there, and the water was rising, but he wouldn’t leave unless he had someone there to take the animals. So we got a bunch of boats and went in there and rescued them.

What about restaurants? Any places you frequent while you’re in town?

There are a couple, but I especially like the barbecue.

Pork or brisket?

The right brisket can be delicious, but jeez, it’s hard to beat the other white meat. The old pig tastes so good. When I cook, I like to grill a steak. I have a rub that I make, and I do the rib eye.

What’s in the rub?

Nuh-uh. No. Not telling.

C’mon.

Nope. It’s not a paprika base, so it’s not real sweet. But it has a lot of dried herbs in it. And it’s…I need that salt kick. I go for 1⅝-inch rib eye. Doesn’t have to be bone-in.

Do you ever miss Los Angeles?

I like visiting there. It’s fine. But it’s no place for a family, in my opinion. Me? I like to live in a place where I like to spend my time, where I have a good relationship with time. I don’t feel like I get ahead of myself as much when I’m in the South as when I’m back in L.A. An hour feels like sixty minutes and a mile feels like a mile. Does time trickle by a little more here? Yes. I think people like it that way.