For all but twelve of my forty-seven years, I have lived in two houses on opposite sides of the same road. I once described in these pages the details and eccentricities of my little community here in Deep Run, North Carolina, made up of other Howards and their flocks, but I left out any mention of Noble’s Chapel, the small country church that sits across the road from my childhood home and at the end of my current driveway. I didn’t write about it because I had never set foot inside. A new visitor would probably find that odd—anyone who stumbles upon Howardville and sees our houses all positioned around a church and a graveyard most likely assumes the church is where we worship and the graveyard is where we rest (especially since the cemetery has the name “Howard” above the entrance). But that’s not the case. Implausibly, the graveyard belongs to another set of Howards, and the church, until recently, belonged to the Methodists. Although my great-grandmother was a founding member of Noble’s Chapel, at some point there must have been a rift, because our troop of Howards became Baptists and took our worship to Bethel a few miles away. Sundays at Bethel were enough for me. I had zero interest in extracurricular religion outside of Vacation Bible School, and the little white church across the road didn’t have a large enough congregation to orchestrate one of those.

That would have marked the end of my tangential relationship with Noble’s Chapel, except that I eventually built a house roughly a football field behind it and my perspective literally changed. If you look out any of the north- or west-facing windows of the fishbowl I call home, you’ll be staring at the church. The sun sets behind its live oak–cloaked steeple. My driveway runs up the side of its sanctuary. Suddenly the church was in my yard rather than across the way. It felt a little like mine, and also a little mysterious.

Since I couldn’t avoid it, I began to tune in to the rhythm of Noble’s Chapel and noticed that there wasn’t much of one to speak of—no choir practice, no Bible study, no business meetings, no pancake breakfasts, no Christmas plays. The only activity happened on Sunday mornings at ten o’clock, when one, maybe two cars would park in the yard for exactly an hour. Half the time it seemed the pastor was preaching to himself, or he hitched a ride with the whole congregation.

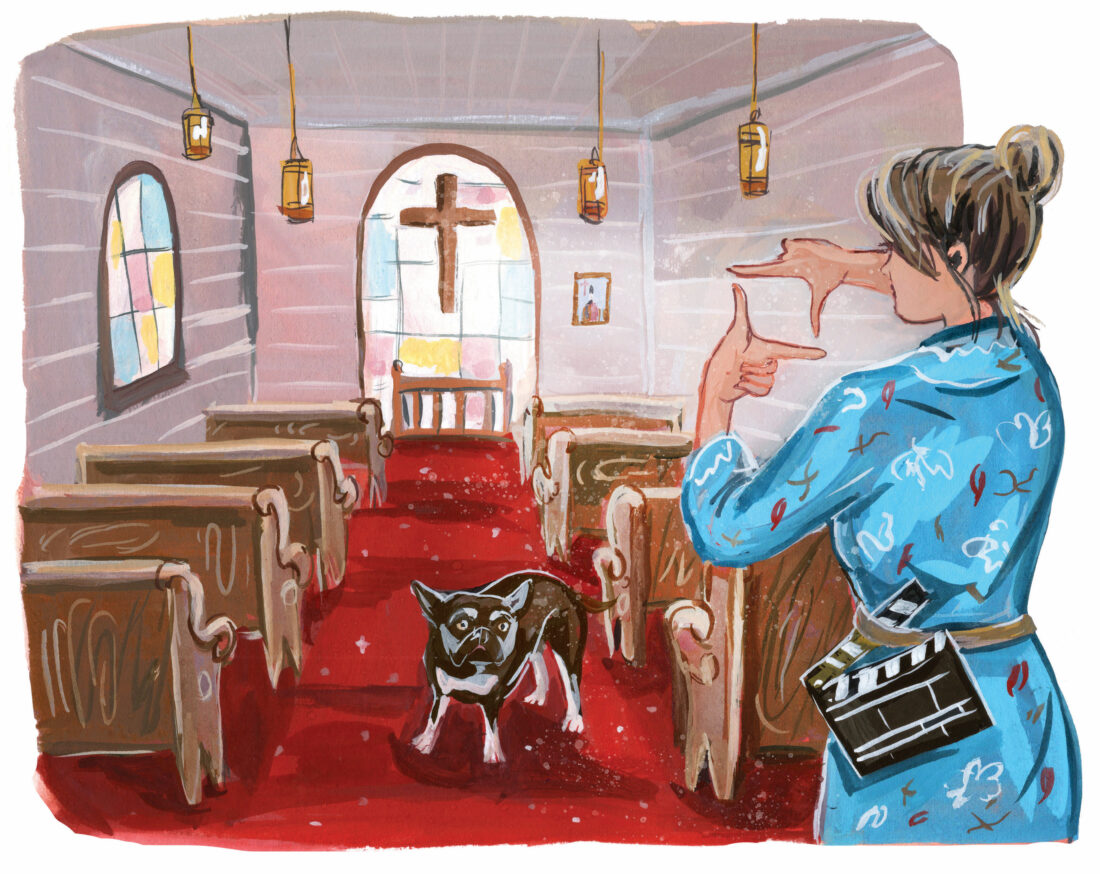

One day on a walk with my dog, my curiosity got the best of me, and I checked the front door. It was unlocked. (I guess the thing about the house of God always being open is for real.) Tina and I helped ourselves inside and saw exactly what country worship in the 1960s must have looked like. In the sanctuary, twenty or so wooden pews stood on a shock of woolly, apple-red carpet that gave the wooden cross hung above the pulpit a Jesus-on-the-crucifix vibe. There were two tiny Sunday school rooms with plank tables and impossibly cute woven wood chairs for children. (I so fell in love with the chairs that I almost lifted one and took it home with me—the church was in my yard, after all, and I was certain no children had sung “Jesus Loves Me” in the place for years.) Behind the sanctuary stretched a long room that could transform from fellowship hall to classroom with the closing of a retractable door. And at one end of that space sat the amenity that lit my heart afire: a galley kitchen with handmade cabinets, a folding panel to hide the chaos of cooking from the peace of prayer, a vintage stove, and a double window that aimed smack-dab at my house. Every time I looked at Noble’s Chapel from that day forward, I wondered what would happen to the little church if the people in those two cars stopped coming.

Then, as the new year turned to 2023, in a move that seemed aggressive, someone from the Methodist diocese walked in and shut down Noble’s Chapel in the middle of Sunday service. I wasn’t there, but even with only two witnesses, word travels fast in Deep Run. Even though I felt for them, I still had to make my move. Less than a year later, the little church was mine.

I knew exactly what I wanted to do with it. I would make one of the small Sunday school rooms a recording studio. The other would be my office. The sanctuary could morph into any number of things—a salon, a grand dining room, a venue for story slams, a tap studio. The kitchen would be a kitchen, of course. I would pick up where I had left off, testing recipes, writing, filming, and generally having a great time working in my culinary headquarters, all of which I had done in another building before I lost it in the divorce. Yet two years after I had bought it, Vivian’s Noble’s Chapel sat just as it had on that fateful January 1.

Life got in the way. I had one restaurant to reopen; a couple more to manage in Charleston, South Carolina; a new one in the pipeline in Duck, North Carolina; plus two preteens and enough trouble keeping my house and yard up to Howardville standards without throwing a church into the mix. For a while I even regretted buying it. Every time I left home, it taunted me like a flag flying at the end of my driveway, reminding me of how silly I could be.

In October 2024, a project I had been working toward for more than three years, with no real hope it would become a reality, came to fruition, and I needed a place to film some cooking demos. Or maybe I pursued the project so I would need somewhere to film cooking demos. Either way, the church plans became a priority. After my niece got married there last January, we tore out the wall that separated the kitchen from the fellowship hall, replaced the stove and refrigerator, installed a stone counter-top and cork floors, and painted the walls and cabinets shades of purple. In March of this year, we started filming the first pieces of my new series for PBS, Kitchen Curious.

My adult life has been framed by things my younger self never saw coming. I was certain I would never move back home, let alone open a restaurant here. I couldn’t have imagined I would make a docuseries about my life and that strangers would ask me how old my children are now or if my parents are still living. I never considered that my marriage would end in divorce or that I would share custody of my kids. I always wanted to be a writer, but in my wildest dreams I never thought that I would write cookbooks or that for five years I would have the privilege of writing a column in the South’s most aspirational magazine. And for a while, I never thought I’d be on TV again. I had imagined this phase of my life to be quieter, more purposeful, less frenetic. Instead, I bought a church. So far we’ve filmed a cooking show in it. God only knows what’s next.