The last and damnedest thing a good dog will do for you is die. You know this going in, but when you’re handed a note by a four-year-old that reads, “Pleez cn I hav a dog???” you think, you hope, you pray it will be different this time.

Maybe you’ll die first.

Our daughter would certainly have formulated that request on her own, but her inscribed copy of Willie Morris’s My Dog Skip didn’t help. In part the inscription says, “Welcome to the world! Don’t read this book until you’re two years old. Get your momma and daddy to give you a dog like Skip when you’re in the third grade.”

Thanks a lot, Willie.

Hell, what did she need with a dog? I’d given her a stone marten. She adored her vintage fur complete with face and paws, the sort once so popular with 1940s movie stars. The two were inseparable. She petted, talked to, and slept with the lifeless pelt, and named it Lassie.

This could not be sustained.

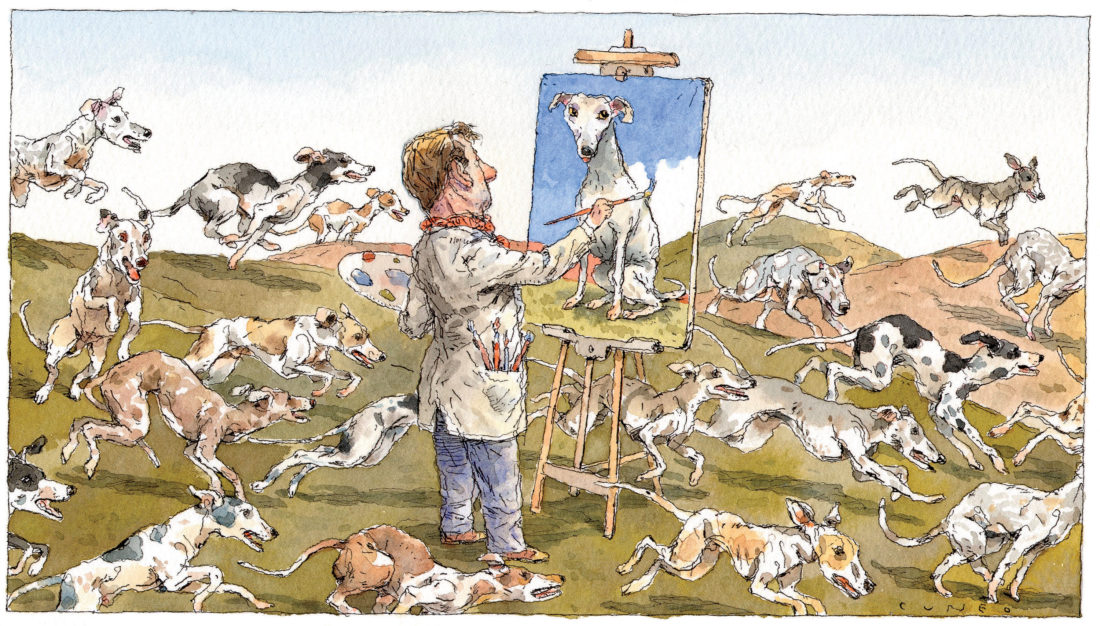

From the beginning, dogs have meant the world to me in both life and art. They found their way into my work early on, mostly as metaphor, stand-ins for the frequent absence of a human presence. Delta Dog Trot—Landscape Askew is one such painting. It hangs in the lobby of Greenwood, Mississippi’s Alluvian Hotel and features a life-size bird dog. I once eased up behind a pair of well-oiled bar patrons locked in animated conversation in front of the painting. I was sure they were overwhelmed by the power of the remarkable artistic achievement before them. Instead, they were reminiscing in a highly emotional way about dogs they had owned but were now departed.

As an artist, I keep a PowerPoint presentation ever ready for museum docents, college classes, and the garden clubs. It changes from time to time, but one segment remains constant: a circa 1951 photograph of my brother and me at our makeshift lemonade stand. “5 cents a glass,” the sign reads. We are flanked by our two dogs of no discernible breed, Prince and Yellow Pup.

Later that summer and not long after the photograph was made, in the clear slow motion of irrevocable memory, I see Prince as he is hit by a car. My grandfather and I buried him in the woods behind his Webster County, Mississippi, home. I can still find the spot—and on occasion, do. To this day, I cannot get through this part of an otherwise entertaining and informative presentation without choking up a bit, as I do now.

But that is all in the past. The problem at hand was a daughter determined to have a dog. It was time for stalling tactics—research at the local library, interviews with dog owners, hours of Animal Planet programming, countless Westminster Dog Show reruns, even a visit to the kennels of a South Florida greyhound track with its owner, but alas these gorgeous, people-friendly animals were just too large. Our daughter was not fooled, and we’d begun to cave. Finally, her ever-resourceful mother found a suitable candidate online. Timbre-blue Whippets in Lexington, Virginia, had a damaged dog in need of rescue.

Timbreblue is a devoted family affair that whelp a couple of litters a year. Some of their pups had been named after things your mother admonished you not to do. “Plays with Matches” was called Ember, “Shows Her Panties” was Fanny, “Don’t Slam the Door” was Banger, and the dog that would become ours, “Blames Her Brother,” was, of course, Snitch.

It’s useful to know that the sight hound that has come to be our modern whippet originated in the north of England in the eighteenth century. This “poor man’s greyhound” was a poacher’s best friend, with quickness, agility, and speeds up to thirty-five miles per hour. The breed was adept at ferreting out rats and rabbits and excelled at “rag racing,” a straight-line contest of whippets sprinting toward their masters, who enthusiastically waved towels at the track’s end. These days owning a whippet means never again having to go to the bathroom alone.

From that initial drive home up Interstate 81 to Fairfax County, Snitch attached herself to the women in my family. She slept with my daughter and shadowed my wife’s every move while seeming to find a place of tolerance in her heart for the alpha male, me.

The dogs of my youth were of equal pedigree but different purpose. Purebred Walker Foxhounds were the preference of my old-school foxhunting grandfather. These working dogs with names like Lucky, Speck, Mary, Sally, Bo, and Buck were all legs, lungs, nose, heart, and mouth. They lived for the chase and had little use for us except to feed or release them downwind of a fox. The thought of snuggling up next to its owner would be as foreign to a foxhound as a passion fruit aperitif prior to a meal of Purina Dog Chow.

Snitch lived for the lap—and luxury. Imperial, elegant, loyal, self-contained, shedding little and barking hardly at all, this remarkably athletic animal ran, jumped, cut, and ripped up our turf with unrestrained abandon. She was an ingratiating joy to have and behold. Pampered and proud, she had no responsibilities except to be among us, but somehow that was enough. It’s counterintuitive, but this extraordinarily active dog out-of-doors became docile and downright cuddly once inside. She treated us like members of her litter, and we were charmed.

And yes, I fed her from the table.

Given the professional stake I have in aesthetics, I’ve got to admit I was seduced by the sheer sculpture-in-motion beauty of this creature. Bred to show, Snitch had been attacked by a Doberman while still a pup. She survived, but with a foot and a half of scars across her back legs and hind-quarters—flaws that only enhanced her uniqueness and made us wonder what she dreamed, what she remembered.

Snitch never forgot from whence she came, and neither did we.

Our relationship with Timbreblue and its extended family continued to open a window into a canine world we had not known existed. Long and detailed stories, literary gems really, were exchanged online. Amusing tales of whippet eccentricities and their shenanigans were shared among breeder and owners, as were the dos and don’ts of disciplining, remedies and cures for ailments, and recommended vets.

And then there was the Annual Family Reunion. All would gather at some preordained time and place to witness seventy-plus whippet kin zooming around an open field like baitfish pursued by a lemon shark. They were lighter than air, inexhaustible, and glorious to watch. The picnic was potluck for the people, Frosty Paws ice cream for the whippets, and then home.

Like all middle-class American dogs, Snitch was the fortunate recipient of unconditional love, devotion, and remarkable medical care. At various times in her life she had the veterinary equivalents of an orthopedic surgeon, an internist, a cardiologist, and a family practitioner. As her heart began to fail, she was prescribed increasing doses of clopidogrel, furosemide, spironolactone, digoxin, pimobendan, fish oil, and toward the end Viagra twice daily, to what purpose I can only imagine, but it all earned her an extra year or two, I suppose.

As our daughter grew up, Snitch grew old. After more than a dozen years of constant companionship, we watched her brindled coat turn gray. There had been countless road trips she patiently endured, tennis-ball-throwing sessions of which she never tired, outdoor restaurants where the waiter brought her water (and of course, I fed her under the table), plaintive looks from the window when we returned home later than she thought acceptable, Christmas mornings when she tore open her own stocking while wearing a pair of ridiculous felt reindeer antlers, and those bony legs and back pressed hard against whomever she selected to sleep beside.

In the spring of our daughter’s senior year in high school, on Good Friday, Snitch breathed her last.

On the third day, she did not arise.

It was over.

“She’s gone,” my daughter sobbed.

Her ashes are buried in a celebrated cemetery on our friend’s farm in St. Michaels, Maryland. She’s in great good company among Fenwick, Ambrose Bierce, Welleran, Charger de Fortunato, Maximilian, and other fancifully named and well-loved dogs. We can easily find the place, and often do.

But Snitch as well as Prince are like unto the dog of Willie Morris’s childhood, the ineffable Skip of whom he writes in the final sentences of his eponymous book.

“They had buried him under our elm tree, they said—yet this was not totally true. For he really lay buried in my heart.”