What kind of day was it? The morning began with an oncologist. She laid out our next year—my wife’s cancer would require radiation, then chemo, then an operation, then more chemo. Meanwhile, my dog, Jesse, was run over by a car. It was that kind of day. I was sitting in an uncomfortable chair in a bland office, struggling to comprehend large, ugly words, when my phone hummed in my pocket. I slyly checked and saw that it was my friend Tom, who was painting my house. I clicked ignore and tuned back in. Right, my wife had cancer. And this was the talk —the big talk—where the doctor tells you how it’s going to be. So many words—adenocarcinoma, endoscopic, lymphatic—words that held little meaning for me, just tiny sonic pricks of dread.

The phone hummed once more. Again, it was Tom—click. Radiation scarring, metastasize—they floated in the air like jazzy verbal riffs, Charlie Brown’s teacher whose voice is a muffled trombone. Again, the phone: Mmmm. Mmmm. Again, click. Leucovorin, adjuvant, epithelial. The doctor’s voice resurfaced into standard English long enough for me to hear “a winter of nausea.” Mmmm. Mmmm.

“You know, this is crazy, but Tom has called me four times,” I said. “Maybe my house is on fire? Excuse me a minute.” I stepped outside of the office to hear Tom, very upset, explain that Jesse had bolted out the front door and had been run over by a car. His pelvis was crushed and he lay in the street howling. The driver freaked out and, howling also, sped off. Tom slid Jesse onto a piece of plywood, loaded him into the pickup, and drove bat out of hell to the animal hospital.

“Mr. Hitt, your dog is severely injured,” the vet said, taking the phone from Tom.

“I see. Look, I am in an oncologist’s office right now. Here’s my question. Will my dog be alive in fifteen minutes?”

“Mr. Hitt, this is very serious,” she said. “You really need to get here right now!” We had this exchange two more times with the vet getting increasingly agitated with me.

“You need to deal with this right now! Mr. Hitt, your dog has suffered a broken pelvis, contusions on the—”

“Let me try this one more time, ma’am. I am in an oncologist’s office. Do you know what that word means?” A gut-wrenching silence seized the phone. For the first time, I felt the awesome power of illness, my first time at playing the C card. It was, paradoxically, invigorating.

“Fifteen minutes,” she said. “Yes, we’ll be here.”

We had gotten Jesse some six years before when my two daughters, in their late single digits, promised they would feed and walk him every day. (I was so young and naive back then.) After giving a stern daddy lecture about rational choice and how we were going to visit lots of kennels and shelters, we never got past the first puppy at the first stop. He was a ball of ebony cashmere who could curl into a perfect sphere of drowsy euphoria. The kids immediately pronounced his name, and we brought him home to an orgy of affection. Jesse seemed, at times, a canine genius, and at others, hilariously challenged. In a few days, he was perfectly housebroken, but he struggled with the basic concepts of “stay” and “come” and “heel.”

We even took him to obedience school. It was in a warehouse and all the owners would stand in a formation with their dogs panting attentively at their sides. Jesse wandered about, as if in a verdant pasture, deaf to all instructions issued in every possible tone of voice—ranging from pleading falsetto to enraged Parris Island drill instructor. Finally, he’d locate some distant scaffolding-filled corner and just plop down like Ferdinand the bull.

When he was two years old, though, he somehow awoke to the pleasures of cooperation. He began to respond to commands and actually seem to take great pleasure in being your best friend.

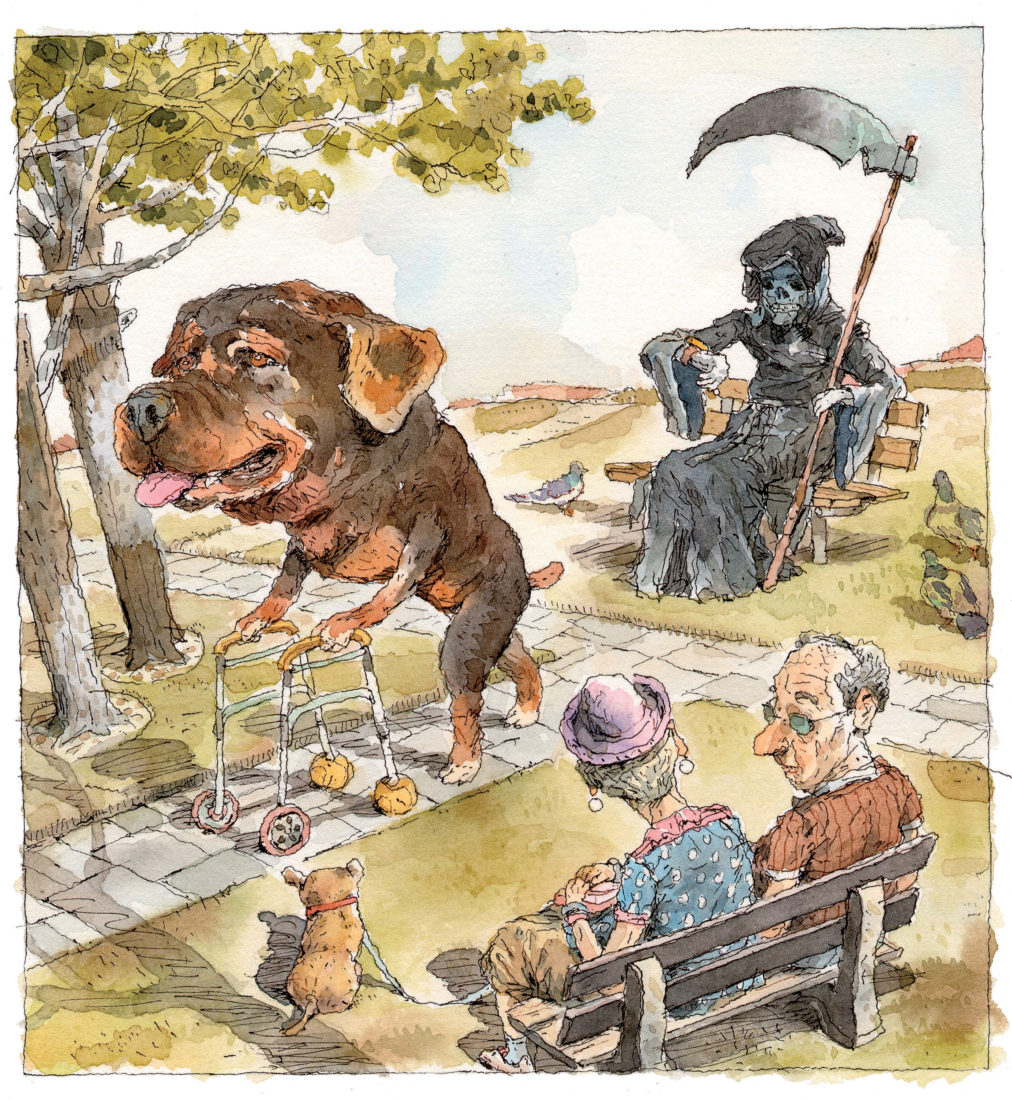

And he grew into a big beautiful dog. He developed some brown on his paws and underbelly and some black on his tongue. Our little mutt revealed himself to be part rottweiler and, probably, chow. He’s muscular, with a low center of gravity and, if you don’t know him, a menacing look. He has an introductory bark that can rattle china off a shelf. But when he cocks his head with half-bent ears as if staring into the abyss of an RCA Victrola, or when he gallops at you like a startled camel in a halo of slobber, it’s impossible not to love the guy. He’s a cute love bunny who just happens to look like the evil spawn of Cerberus.

At dog parks or in chance encounters, Jesse’s a cheap hump and totally GGG, thrilled for a ride and happy to assume the position. He’s insanely inquisitive, and takes it as his life mission to chase down any nearby rodent and bark at it before looking back at me, as if to say, “I got your back, boss.”

Being run over by a car was a kind of blessing. Lisa and I love this dog, and focusing on his life-or-death crisis made our affairs seem languidly manageable (which ultimately they were). On the way over to the animal hospital, I called my brother and sister, both crazy dog people, and sought their advice. Big dogs don’t do well with broken bones, I was told, and give him a day or so and then decide if you need to put him down. A hard decision, they told me, but, sometimes, the only humane choice.

The vet, a sober brunette in her thirties, ushered us into the intensive care unit, where Jesse lay knocked out on a gurney, his paw shaved to the skin, an IV snaking out of his shank and into a bottle on a hook. He looked dead, a preparation for the decision we might have to make.

The vet asked us to step into another room to see the X-ray she had taken. This was the talk—the big talk—where the doctor tells you how it’s going to be: that we needed to keep Jesse in the unit overnight. He might well die. She showed us the very image of his crushed pelvis. She explained how very soon, within a few days, we’d need to schedule major surgery. She said, “There is no other option.”

People of Scottish descent, according to the ethnic slur, are notoriously miserly, and my mom’s family is nothing but High-landers all the way back. So, in the midst of all this breathless talk, I asked the rude question. How much am I in for so far? She said, “Seven hundred dollars.” And for the overnight stay in the ICU? “Fourteen hundred dollars more”—although it was clear from her tone that she considered my questions vulgar. And for the surgery? “Twelve thousand dollars.”

The whole room seemed to stand still. Most of us don’t carry animal health care insurance, so veterinarianism is a fee-for-service business.

Again she said, “There is no other option.”

I now bore down into her eyes. “Here’s the bad news,” I said. “Where I grew up, there is another option.” I could see she understood what I was suggesting, but she cocked her head, as if she were seeing the real me for the first time—a Victrolan vortex of evil. “I can put Jesse down.”

She could not look at me, as I had now morphed into Heinrich Himmler. That transformation was cemented the next minute, when I coldly insisted that I wanted my dog. Now.

I paid the bill, situated Jesse into the sling of a blanket, and placed him in the back of the car. At home, he lay half curled all day on the kitchen floor, motionless, a black crescent of suspended foreboding. By sundown, Jesse was awake but unable to make eye contact. At bedtime, I headed upstairs and Lisa said she’d follow. When I came down the next morning for coffee, I found my wife sleeping on the linoleum beside our pup marooned on a pile of blankets.

He peed red that morning and I sped off in the car to get more doggie downers. We narcotized Jesse silly those next few days, and then carried him and his blankets out to the backyard where the temperate days and nights made it easier for him. One morning he sipped some water, and he looked me in the eye. I choked up. Even still, if you petted him at all, he’d grip your hand with his teeth. Jesse was never a biter and even in agony, he still wasn’t. He’d just put his teeth on your hand to let you know: Don’t even think about touching my hip.

At times he’d drag himself off the blanket and make a bit of a pee. I’d gently pick him up—his teeth on my hand the whole time—and put him back on the blanket.

One afternoon, about ten days after the accident, I was standing on the porch talking on my flip phone when a squirrel bolted across the yard. Jesse scrambled up on three trembling legs and let out one of his legendary barks. It was the first time I’d heard it in nearly two weeks. The squirrel was gone as Jesse looked back over his shoulder, to let me know I was safe. I snapped the phone shut and burst into tears.

I don’t want to put down animal hospitals, but I suspect he’s a lot happier with his current pelvis than any trussed with steel pins. There’s no limp. He’s back to his old self. He sprints like a streaking Weimaraner.

And by sprints, I mean galumphs, and by streaking, I mean drunk, and by Weimaraner, I mean warthog.

Jesse totally recovered and it would be falsely high-minded of me not to mention that I’m about fourteen thousand dollars richer. Good dog.