Perhaps it’s our ongoing desire to tame nature, or at the very least understand it, that has compelled generations of people to keep gardening journals. We have records dating as far back as 1305, when Pietro Crescenzi, the fourteenth century’s Monty Don and a Bolognese lawyer, compiled Ruralia Commoda, a Medieval hot take on all things horticulture. Henry VIII once owned the tome, which recommended planting squash near human bones for faster fruiting and described cucumbers that shook with fear at the sound of thunder. Duly noted.

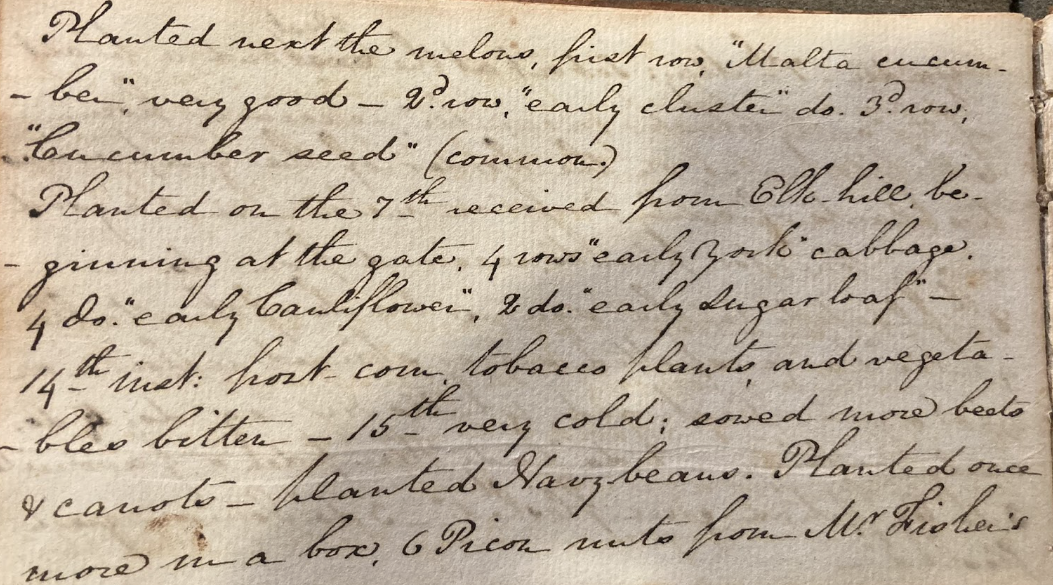

Shivering vegetables aside, writing down a day’s efforts in the garden has long been a helpful guide to the seasons all over the world. Here in the South, while transcribing the diary of Carter H. Harrison, the fifth owner of my eighteenth-century home in Scottsville, Virginia, I recently stumbled upon his own cultivation accounts from 1834:

May 4

Planted next the melons first rows Malta cucumber – very good. 2nd row “early cluster” 3rd row, cucumber seed

Planted on the 7th received from Elk Hill beginning at the gate. 4 rows “early york cabbage”

4 rows “early cauliflower” 2 rows “early sugar loaf –

14th husk corn, tobacco plants and vegetables bitten 15th very cold; sowed more beets & carrots – planted Navy beans. Planted once more in a box. 6 Pine nuts from Mr. Fisher’s.

We know that when Harrison bought our house, the contract included “his entire estate—land, stock, farming implements, and servants.” And while we have yet to uncover records verifying just how many enslaved individuals lived on the property, we can be sure they were the ones doing the heavy lifting that he notes—people and work he sadly omitted from his ledger.

What Harrison’s records do convey, however, is a compulsive predilection for tracking what’s in the soil. And it’s the same for me today.

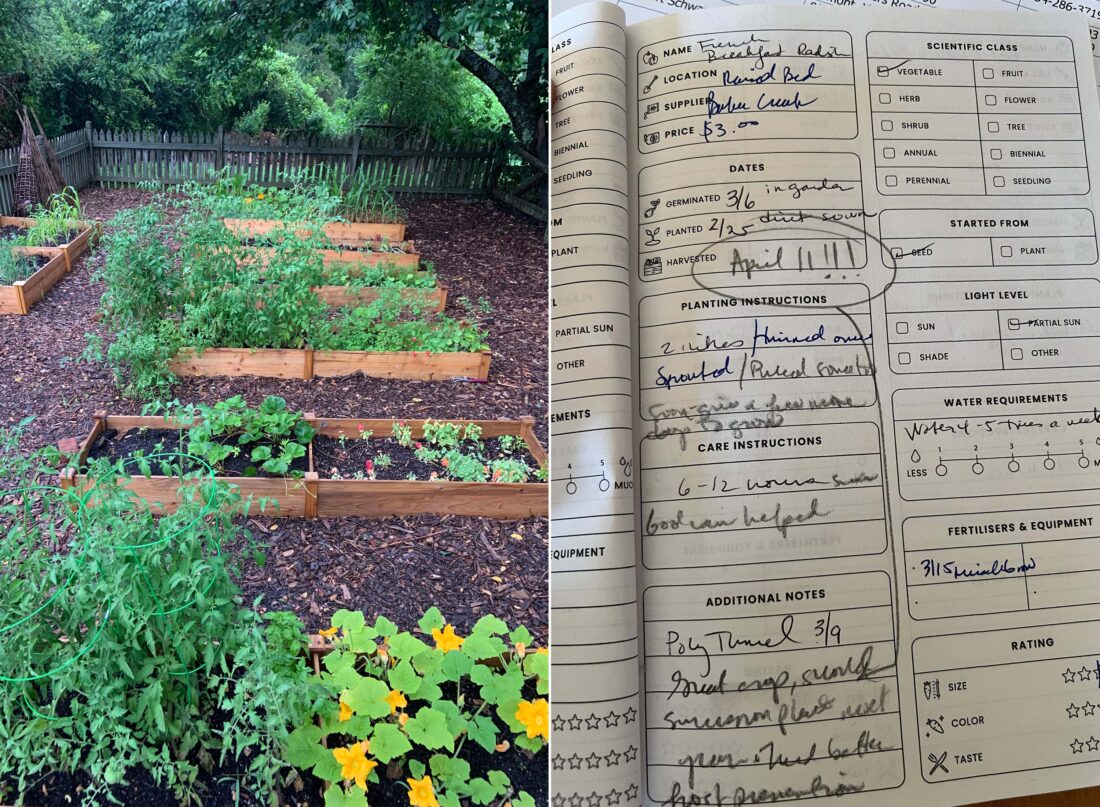

Last Christmas, after I learned that my darling, hilarious, Shakespeare-reciting seventy-one-year-old mother had early onset dementia, I channeled my devastation into the Baker Creek Heirloom Seed catalog. One $200 order later, I found myself building raised beds like my mom’s remaining memory depended on it. My husband and I together hauled truckload after truckload of wood chips into my new kitchen garden, our hands chapped from the cold, a painful but welcome distraction from my personal heartache. I carefully labeled plant markers and staked them next to seedlings I nursed in my basement all winter on a rickety ironing board, watering them with more than a few tears. And I kept notes. So many notes in a brown gardening journal I filled daily.

It will not surprise a veteran gardener to learn that this activity was incredibly therapeutic. I’d go so far as to say lifesaving. (Don’t believe me? Check Ruralia Commoda. I’m sure Crescenzi has a chapter on the healing powers of documenting one’s first homegrown tomato or the panacea of filling a salad bowl with one’s own seed-to-table nasturtiums.) But what I didn’t end up with was a very usable log to reference. My scribbles are shoved into such tiny lines that they’re barely legible.

I’ve been looking for a new kind of journal that will help me efficiently keep tabs on this year’s harvest. No easy task. It turns out, there’s a hole in the market when it comes to landscape logs. Too often they’re laid out simply, like a tween’s first diary only with the heart-shaped lock missing. So I set aside Crescenzi and turned to the modern gardening experts, asking them what tools they used to keep track of their labors. Their answers were almost as varied as the plant kingdom.

“I’m probably among the most geeky of folks you could ask,” Jenks Farmer told me. The South Carolina plantsman, award-winning garden designer, and author says he uses a database to track his garden’s growth. “I use FileMaker. It’s more for record keeping and sharing info than for planting plans. And I don’t do it for all plants—just things that are rare, things I think I might sell, and because I’m a crinum collector, every single crinum.” Farmer is so meticulous, he tracks the source and starting date of each plant and then adds photos to FileMaker. “I can technically walk through my plants and access or add to the database from my phone, which is convenient, but I tend to resent my phone needing attention when I’m trying to be with my plants.”

For some gardeners, a log isn’t necessary. Amanda McNulty of SCETV’s Making It Grow television show says, “I don’t even know the dates of my children’s birthdays, much less anything about when I plant, which is mercurial.”

Others insisted all I needed was a good old-fashioned notebook. Zack Snipes, a horticulture agent at Clemson Cooperative Extension Service, says he and his farmer friends keep it simple: “They’ll just write down what they did that day and refer back to it over time,” he says. “I do the same myself.”

For Shawn Cossette, owner of the Charlottesville, Virginia, floral and event design business Beehive Events, keeping records is a bit more ad hoc. “I am the type that has garden notes everywhere, and I mean everywhere,” Cossette says. “My issue is that I am both analog and digital and find it impossible to connect the two in one place.” Considering the beauty of the flowers at her Fat Cat Farm, this is reassuring. Perhaps a tidy journal isn’t the key to a fruitful landscape after all.

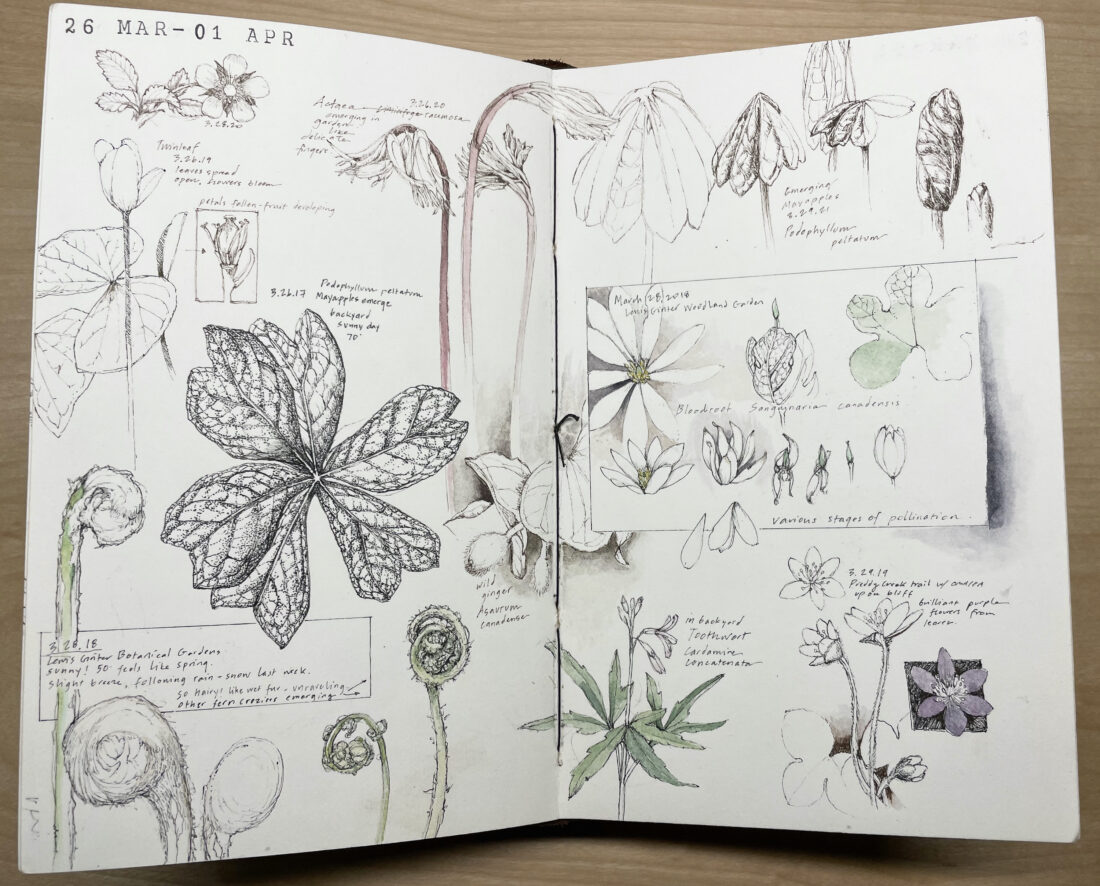

Maybe a more artistic approach is the solution. Lara Call Gastinger, the chief illustrator of the book Flora of Virginia, a complete guide to the state’s native plants, pioneered the concept of a perpetual journal, an illustrated gardening log. “The pages are marked with the dates of the fifty-two weeks of the year in the upper left corner of the spread, but the book is not tied to a specific year,” Gastinger says. Instead, the artist uses the journal to record observations during a particular week of the year, which they can return to in subsequent years.

The resulting sketches paint a multilayered picture. For example, she might draw a thriving turkey tail mushroom sketched in 2021 beside a 2023 fallen oak leaf barely recognizable through its lattice of holes. It’s the kind of book a gardener could look back on and remember that, be it the joy of discovering the first shoots of spring or the anticipatory grief of watching a once dazzling bloom’s premature decline, there’s beauty in all of it.

For now, I’m still on the hunt for a good gardening journal, but I’ve planted my first rows of Kelvedon Wonder peas and carefully placed glass cloches over them. Harvest may feel a long way off, but I’m thinking of something my mom might say: “Sweet flowers are slow, and weeds make haste.”