When the Hemingway Home first opened its foliage-framed gates to the public sixty years ago, visitors got to enter the preserved Key West oasis that inspired one of America’s literary heroes. Today, the property looks much as it did when Ernest Hemingway lived there in the 1930s: typewriters are strewn about desks, vibrant mustard-colored art deco tiles line bathrooms, and of course, dozens upon dozens of six-toed cats roam. “We have fifty-nine cats at the moment, and about half of them have extra toes,” says Alexa Morgan, the director of public relations at the Hemingway Home and Museum.

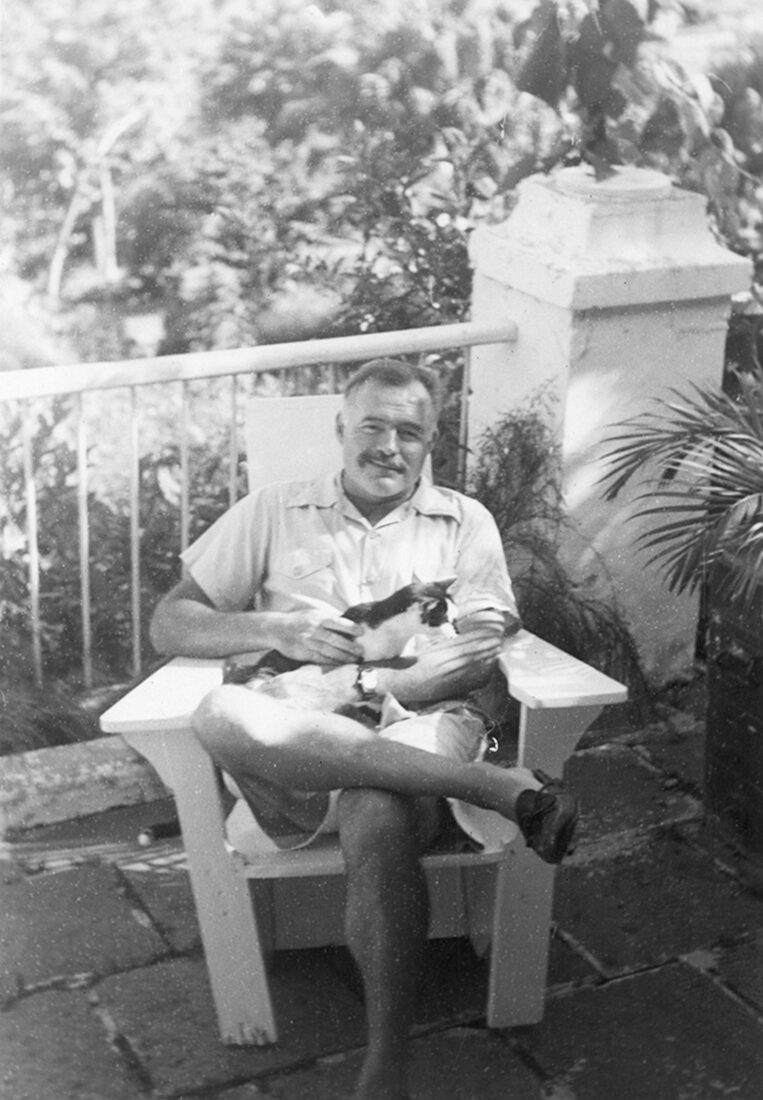

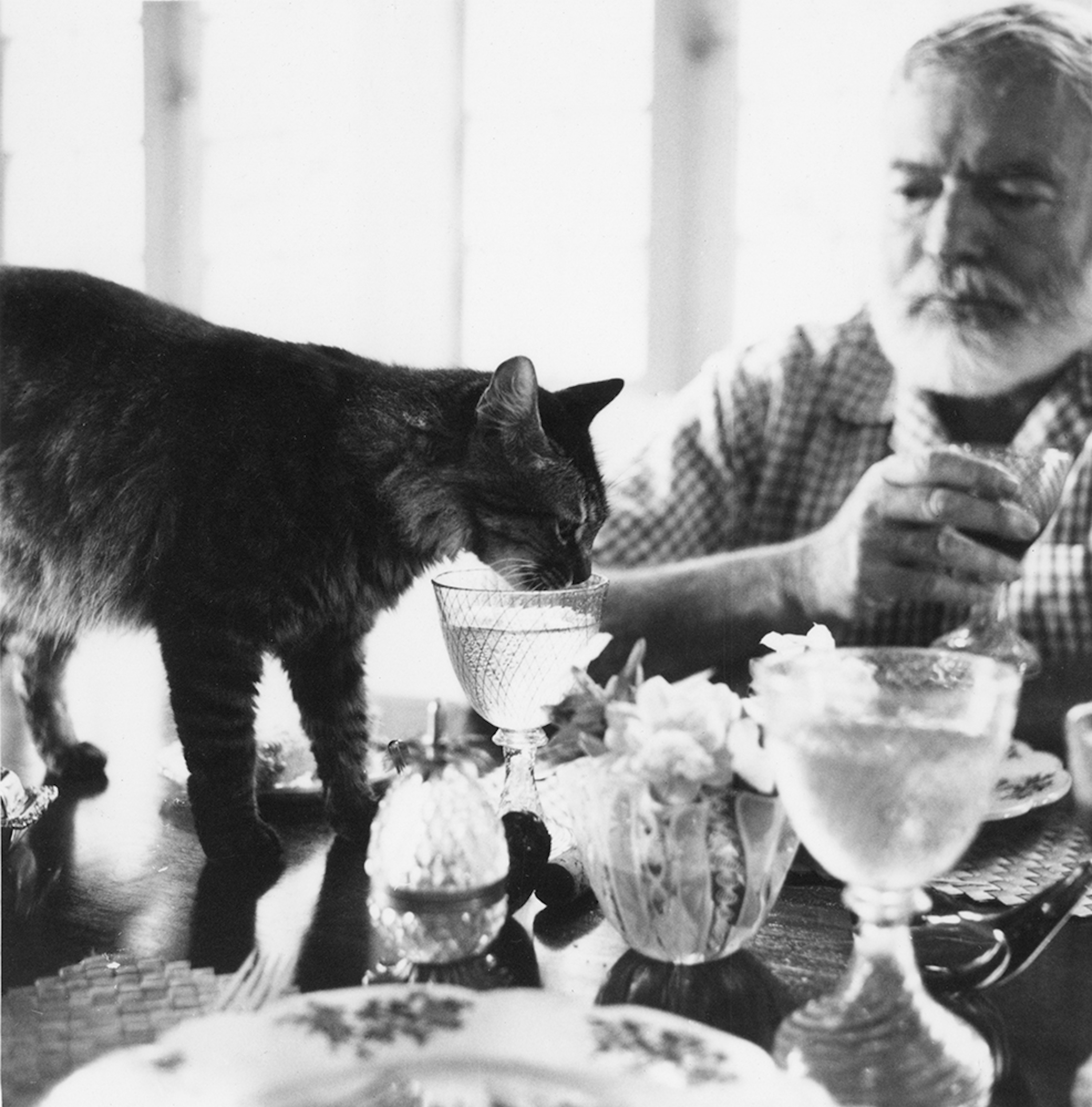

The Old Man and the Sea author was not the first person to take interest in polydactyl cats, but he popularized them to the degree that they’re often referred to as “Hemingway cats” rather than by their scientific name. His affinity for felines in general is clear in letters to friends, but the six-toed ones most captured the attention of visitors to the home, then and now.

The cats’ massive mittens are the result of an easily inheritable genetic mutation that gave them an advantage in catching prey. “Most port towns are heavy with these polydactyl cats because ship captains thought they were good luck, and because they were good hunters, they helped keep vermin down,” Morgan says.

One such seafaring feline was Snowball, a white polydactyl cat who sailed from Massachusetts to Key West with her owner, a man named Captain Stanley Dexter. It was this creature who first sparked Hemingway’s curiosity, and the two—writer and feline—became well acquainted on the docks of the island. Noting Hemingway’s interest, Dexter gifted him one of Snowball’s polydactyl kittens, Snow White, who quickly became a part of the family—and maybe gave Hemingway some peace of mind, too. “Hemingway was very accident-prone, so he was very into polydactyl cats for the good luck aspect,” Morgan says.

Many of the cats currently residing at the Hemingway Home are descendents of Snow White and her suitors, aka the neighborhood cats Hemingway fed. Since the museum opened, its cat population has stayed pretty stable at around sixty felines, give or take. That’s deliberate: While the vast majority of the animals are spayed or neutered, some are kept intact to continue the lineage of Snow White. “There’s no excessive breeding. One lucky couple a year gets to have a litter, and we monitor the relations and relationships,” Morgan says.

This year, only one kitten was born, a little gray cat named June Carter Cash. Like all the other cats at the museum, her name came from a staff vote. Usually the cats are named after a famous individual from Hemingway’s time. “We have a John Wayne.” Morgan says. “He’s a big baby, and he always wants to be cuddled. He’s everyone’s favorite.”

Although he had many cats over his lifetime, Hemingway did not take their deaths lightly. Upon having to shoot one, Uncle Willie, after he got hit by a car, Hemingway wrote: “[I] have had to shoot people but never anyone I knew and loved for eleven years. Nor anyone that purred with two broken legs.” At the museum’s cat cemetery, every departed feline since the 1980s—from Mark Twain to Simone de Beauvoir—is commemorated with a plaque.

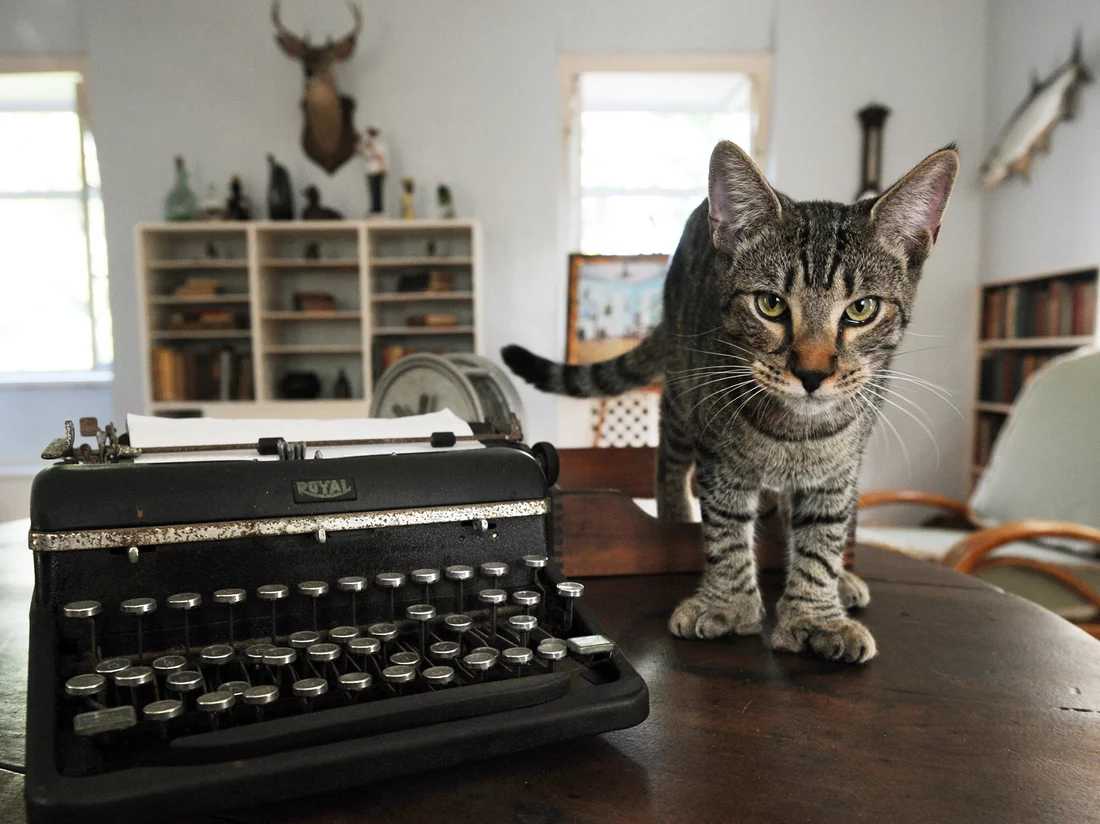

As for the living cats, unlike visitors they have free range of the property (and a dozen dedicated staff to tend to them), from gardens to roped-off areas. Behind signs that read “Please do not sit on furniture,” the Hemingway cats delight in, well, sitting on furniture. And in true Key West fashion, they take the job of living on island time seriously. No nook is off limits to the felines, and visitors can find them peacefully snoozing on Hemingway’s bed, writing chair, or desk, blissfully unaware of the history beneath their six-toed paws.