Talk about a stellar run: In 2021, the director Liesl Tommy gave us Forest Whitaker’s fine, angry portrayal of Aretha Franklin’s hard-driving preacher-father C.L. Franklin in the acclaimed Respect. Set to be released late this summer is Gareth Evans’s police thriller, Havoc, with Whitaker opposite Tom Hardy’s down-and-out cop. At some point this September, the principal photography is slated to begin in Atlanta and New York for Francis Ford Coppola’s long-awaited Megalopolis, starring Whitaker in an A-list ensemble cast that includes Cate Blanchett, Jessica Lange, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Jon Voight.

That could be a meaty enough to-do list for many actors. But at the same time, on the small screen, Whitaker has been drumming his special gravitas into the title role as New York’s go-to 1960s gangster Ellsworth Raymond “Bumpy” Johnson, in Chris Brancato’s Godfather of Harlem. The series is now in its second season.

Here’s an underutilized Hollywood metric for assessing actors: As riveting and well-lauded as Whitaker’s performances are, putting the quality and the depth of the work aside, just a glance at this most recent shortlist of directors should tell us what we need to know about the man and his range. Liesl Tommy, the Black, South African, Tony Award–winning stage director; Gareth Evans, the young, white-hot Welsh action-film director; and finally Coppola, arguably the greatest living American director bar none, are queued neatly bidding for Mr. Whitaker’s time. Large chunks of it. And these are just three of his most recent projects.

Not a bad spate of work for a lad from Longview, Texas. Whitaker moved with his parents from Texas to Southern California during his boyhood, a radical uprooting that crucially landed him smack in Los Angeles and, slowly, introduced him to his future on both sides of the camera.

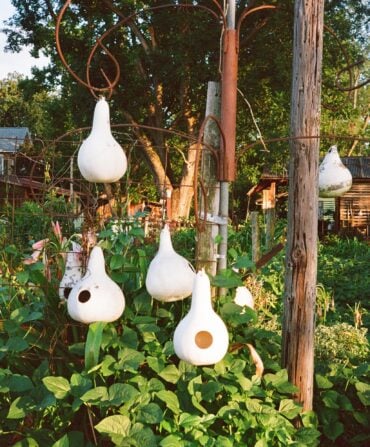

We can debate how much Texas and the South left in the man, but that question was once proudly settled by Whitaker himself, in an interview with Texas Monthly: “My parents moved to Los Angeles when I was really young, but I spent every summer with my grandparents, and I’d stay with my grandfather on the farm in Longview. He was retired from the railroad, and he had a small farm with some cows and some pigs. I remember part of my youth was feeding hogs and plowing fields and stuff, so that’s a part of me.”

No less a trenchant observer than the Los Angeles Times and IndieWire writer Fred Schruers provides us with the broader view of how Whitaker’s intensity and presence have fashioned the arc of his (to date) nearly ninety-film career. (That’s as an actor; Whitaker has also produced more than thirty films and directed five.)

“Forest came into wide recognition of his deep talent rather late, in Hollywood career terms,” Schruers explains. “He was in his mid-thirties in the late 1980s, when he played the 1950s-era Charlie Parker for Clint Eastwood in Bird. He made the most of that script’s tart, noir dialogue to help define Parker’s otherworldly genius. Whitaker didn’t look quite as spent as Parker did when Charlie died at thirty-four, but Forest brought a real world-weariness to every scene in that film. Four years later, he showed such vulnerable youth as the British soldier kidnapped by the Irish Republican Army in The Crying Game, and years later, delivered his elegantly bleak, terrifying performance as [Ugandan dictator] Idi Amin in The Last King of Scotland. That’s intelligence and deep homework meeting acting chops in a way that comes off so naturally onscreen. Like they say in baseball, man can hit anything you throw at him.”

The Last King of Scotland won Whitaker a well-deserved Oscar for Best Actor in 2007, and nearly every other acting award given for major dramatic work that year. Among those were awards from film critics in Los Angeles, New York, Washington, Toronto, and London, a Golden Globe for best actor, the British Academy Film Award for best actor, and a Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance. Nor should it come as a surprise that the United Nations’s own correspondents’ association named him an advocate.

The Amin role was a paradigmatic Whitaker job of going in deep for his director, in this instance the talented Scottish helmsman Kevin Macdonald. For the performance, Whitaker gained fifty pounds, went out to Uganda, learned Swahili—the highly idiomatic mélange of East African tribal languages and Arabic—and interviewed many of Amin’s victims and their families, as well as Amin’s own family. In addition to delivering a precise Anglo–East African accent to his English in the film, Whitaker brought to his portrait of the madman a Beethoven-like grandiosity reminiscent of Sir John Gielgud’s Hamlet. Yes, Amin was a raging monster, but the most shocking and literary gift in the performance was that Whitaker brought us the man under the madness and let us explore him.

His supporting roles have been no less broadly selected, as in Oliver Stone’s Platoon; The Color of Money; Good Morning, Vietnam; and Robert Altman’s fine fashion-world satire, Prêt-à-Porter. Among his leading roles, Whitaker was badly served in Lee Daniels’ The Butler by an overambitious script that tried to place his character at too many major twentieth-century historical crux points for the narrative to be believable. Nevertheless, Whitaker did what he had to do to anchor the story from flying away. As the cinematic version of real-life White House butler Eugene Allen, playing opposite Oprah Winfrey as his wife, Whitaker treats us to a nobly understated Black man in the direct service of the presidents during the raging 1960s.

The sum of such nuanced work is why, this past May, Whitaker received an instant standing ovation as he bestrode the stage of the Grand Théâtre Lumière to accept his Honorary Palme d’Or for lifetime achievement in film at the kickoff gala to the seventy-fifth Festival de Cannes. Whitaker is no stranger to France or the French—he has long been made a Chevalier, or knight, of the country’s Ordre des Arts et des Lettres cultural honors. But this outpouring of affection at the Palme d’Or was very much ad hominem, marking his directorial efforts, his breadth of roles as an actor, his directing and producing, and his long-standing charitable engagement well beyond Hollywood. It can be a long way from a Texas boyhood to the main stage of the Lumière in Cannes, and perhaps it is, but Whitaker seems to have bridged that span with sovereign ease.

None of that was lost on the Cannes authorities. French is the language of diplomacy both for its finesse and for its expressive power, and the president of the Cannes festival, Pierre Lascure, made sure to deliver both.

“It is a tradition for the Festival de Cannes to honor those who made its history and Forest Whitaker is one of them,” Lascure said. “He is this young actor that Clint Eastwood revealed in Bird, and that man who broadens his view of the world to offer it to those who suffer and those who fight. The full honors belong to Whitaker. This Palme d’Or is a gesture of gratitude from the world of cinema.”