Carold Wicker hasn’t just been an avid vegetable gardener for much of his eighty-four years living in the Dutch Fork region of central South Carolina. The auto repair shop owner also has been saving the heirloom seeds favored by his family and other neighboring relatives for generations.

So when Dr. David Shields, a University of South Carolina English professor with a serious sideline in preserving Southern foodways and ingredients, got word that Wicker had greatly curtailed his gardening pursuits due to failing eyesight, he eagerly accepted an invitation this past November to take a peek into the collection.

“Saved seeds can have limited viability, and with Carold now able to save just a few new seeds each year, we wanted to make sure we knew what was in there,” Shields says.

In this case, the “collection” was a dinged-up Montgomery Ward chest freezer stacked to the brim with thousands of plastic baggies containing seeds. What it lacked in presentation, it made up for in easy-to-fathom organization, the baggies bearing the name of the seed and what year it was saved. As with an archeological dig, each strata was a journey farther into the past, with seeds at the bottom dating to the late 1960s. Once sorted, the discoveries were revelatory, including varieties of beans, melons, and collards that are exceedingly rare or even thought to be lost. (See some top finds below.)

“In the mid-twentieth century, agronomics took over plant development, so factors such as disease resistance came to outweigh flavor,” Shields says. “Luckily, all across the South were these guardians of classic varieties that had stood the test of time. The old heirloom stuff was designed to taste good.”

Shields obtained portions of Wicker’s most recent grow-outs of these seeds, repackaged them into glass vials, and transferred them to Clemson University’s Heirloom Collection. (Yes, USC and Clemson academics are permitted to converse, even collaborate.) From there, the most significant varieties will be provided to experienced local growers to produce new crops while also selecting the hardiest plants to generate future cultivars that are more tolerant of heat and pests. “Sometimes these older plants are more adaptable than you think,” Shields says. “They might survive where a modern, less genetically diverse cultivar might all die.”

Best of all, when viability has been established in two or three years, even the average home gardener will be able to obtain seeds through the Clemson program and perhaps even through seed catalogs specializing in heirlooms.

A few highlights from Wicker’s collection:

Rattlesnake Watermelon: Originally bred in Augusta, Georgia, in the 1850s by crossing the extinct Lawson watermelon with the Mountain Sprout watermelon, this twenty-pound picnic melon is oblong with lengthwise stripes that ripple like snakes. Inside, the red flesh has superior flavor.

African Cantaloupe: Wicker grew this pink-flesh melon from seeds brought back from North Africa by a brother who served there during World War II. He says it offers the most distinctive taste of any muskmelon he’s eaten, with a hint of nutmeg.

Dutch Fork Pumpkin: A tan, lobed pumpkin grown in the Dutch Fork area around Newberry, South Carolina, since the early nineteenth century. Circumstantial evidence suggests it is a descendent of the ancient Cherokee Pumpkin of Native origin.

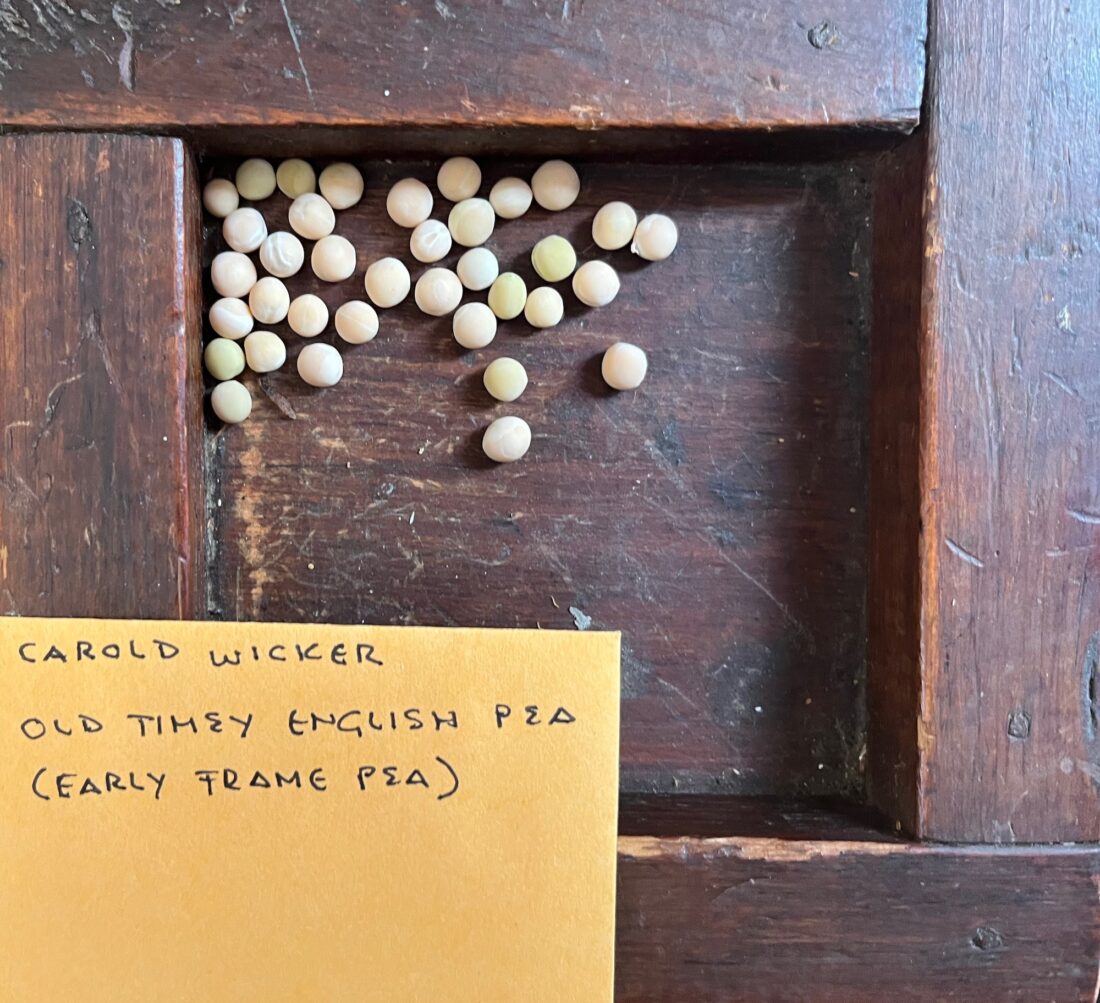

Early Frame Pea: As hinted by the name, this earliest maturing of the classic English garden peas can be planted in a cold frame in mid-December and transplanted in mid-March. A 2022 grow-out of this seed indicates it is the same pea once planted by Thomas Jefferson at Monticello and thought to be extinct.

Black Butterpea: This tender pole bean forms compact pods and tender, dark red beans favored in the Dutch Fork as a summer side dish, boiled and dressed in melted butter. “I think this one might have commercial possibilities,” Shields says.

Small Coastal Cowpea: Hailing from the Carolina Lowcountry, this robust grower was famous in the early twentieth century for performing well in wet environments with salty soil. It was primarily used as a feed crop.

Heading Collard: An interesting variety related to cabbage collards, which are German cabbages that lost their tightly clumped heads once grown in the South. The Heading Collard is a further adaptation that retained some of its genetic diversity to again form a small semblance of a head.

Little August Peanut: A unique peanut with the size and seed configuration of the Carolina African peanut that was restored a few years ago, but it matures more quickly. “Plant it in August and it can produce a crop before December,” Shields says.

Steve Russell is a Garden & Gun contributing editor who also has written for Men’s Journal, Life, Rolling Stone, and Playboy. Born in Mississippi and raised in Tennessee, he resided in New Orleans and New York City before settling down in Charlottesville, Virginia, because it’s far enough south that biscuits are an expected component of a good breakfast.