Tom Boozer straddles a low carving bench in an open-air workshop on South Carolina’s Yonges Island, where a winding creek pours into the Wadmalaw River southwest of Charleston. A block of wood is C-clamped tightly to the bench. Boozer has a drawknife in his hands, an ancient one, perhaps 150 years old, and as he angles the dark steel across the wood, shavings peel off and drop to the floor. It doesn’t take long. In a few minutes, the arcuate back of a duck appears. In a few more, the roughed-out edges of wings, then the dip of a neck. Shavings pile up around brown leather boots. The shop smells of pitch and paint. And minute by minute, everything that is not a duck lies drifted up on the floor. When Boozer removes the clamp and holds the bird, you can see it plain as day, and you wonder why you did not see it before.

Boozer carves birds in a rare style—hollow-bodied decoys, a design with roots in mid-nineteenth-century Connecticut—and he is one of the most highly sought carvers in the country. After he shapes the birds

with drawknife and wood rasp and handsaw—Boozer uses no power tools in the process—he saws off the bottom few inches like a board, hollows out the body with a mallet and chisels, and then reattaches the bottom with copper boat nails and marine glue. The entire decoy is primed with spar varnish and painted with exacting detail. A single feather might require three colors. To create the depth and dimensionality of individual feather barbs, Boozer drags a comb across the paint. “There’s easier ways to make a duck,” he says, laughing. “But they’re not my ways.”

A gunning rig of a dozen Boozer decoys might fetch $4,000, depending on the species. And while there’s no question that many Boozer birds never see a sunrise, he builds each one, as he says, “to go overboard,” be it destined for the mudflats or the fireplace mantel. “I’m not gonna make one just for the shelf. You can put ’em on a string and hang ’em in your kitchen and that’s fine. But they’re all made to hunt.”

Boozer grew up in Columbia, South Carolina, or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that Columbia was his childhood home. His real growing up, his formative experiences, took place a half hour north, outside of Lexington, on his grandfather’s forty-eight-acre farm. As a kid, Boozer was there every week. He milked cows and killed chickens after church on Sundays. He hunted squirrels and ducks and quail back, as he says, “before quail got to hurting.” And it was on that farm that he met a renowned woodworker, Olin Ballentine, who mentored Boozer in the ways of wood grain and grinding wheels and hand tools that were already giving way to the power cord. “Once I met Olin,” Boozer says, “it just seemed like I was born for it. Born for them old tools and ways to preserve history.”

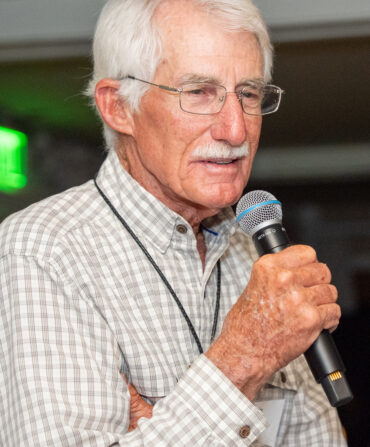

Photo: Imke Lass

Rarest Forms

A collection of finished ducks.

VIDEO: In the Shop with Decoy Maker Tom Boozer

Preserve it he has, and not just by carving ducks. Ballentine once told the impressionable young Tom, “If you call yourself a woodworker, you ought to be able to make most anything out of wood.” It’s a charge Boozer has taken to heart. Though he has now carved more than 3,100 birds—not only ducks and geese and swans but also turkeys, ruddy turnstones, greater yellowlegs, and long-billed curlews—Boozer is also known for museum-quality boat models, from tiny replicas of old market-hunting craft such as punt boats and battery boats to a series of sought-after replicas of Jenny, the shrimp boat of Forrest Gump fame. He’s working on models of the oyster sloops that plied South Carolina waters in the first half of the twentieth century, and he is an accomplished carver and maker of dioramas, having recently completed an installation of a Lowcountry cotton plantation at the Edisto Museum.

Photo: Imke Lass

The last step in Boozer’s process––cleaning varnish off the glass eyes.

But Boozer began with the birds, and it’s to the birds he most often turns with his father’s wood rasp and his grandfather’s brace and bit in hand. “I’m a duck hunter,” he says. “That’s why I’m here. It’s part of what I do.”

In the last step before affixing lead ballast to the bottoms and tying on the anchor and line, Boozer uses a pocketknife to scrape the German glass eyes clear of the layered coats of varnish and paint. “That’s when the bird all of a sudden comes alive,” he says. “It’s like it wakes up, all bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, right there in your hands.”