As hard as it is for me to believe, it’s been thirty summers

now since I first drove up Sewanee Mountain—also called Monteagle Mountain, in southeastern Tennessee—to matriculate as an undergraduate at the University of the South. That’s the same gulf in time that separated my arrival at Sewanee from the launch of Sputnik, and the same gulf that separated the launch of Sputnik from the Coolidge administration. So it’s a fair chunk of what Robert Penn Warren tended to call “Time,” with a capital T.

And this summer is like all the others: My family and I will migrate to Sewanee for as long as we can. Our children—now ranging in age from nine to fifteen—have never known a world without a season of bicycles, hikes on the Perimeter Trail that rings what’s called the Domain, and, truth be told, domestically bitter Scrabble wars on the porch of our house. (My wife and I are not particularly congenial competitors—much to the amusement of our progeny.) In the age of Taylor Swift, it’s a summer experience that evokes the fiction of Peter Taylor. Which can’t be a bad thing.

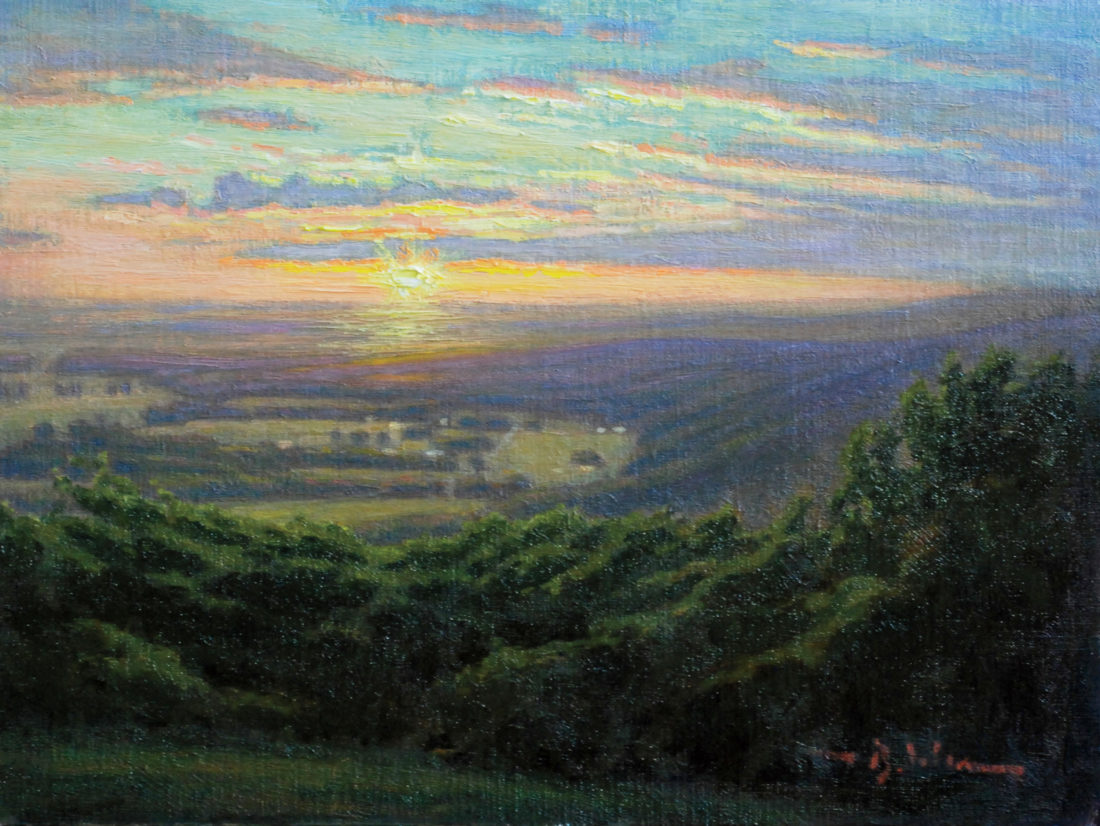

The name of the town the Episcopal institution inhabits and a synonym for the university, Sewanee is geographically found on thirteen thousand acres of the Cumberland Plateau. Yet as generations of alumni, professors, trustees, regents, and bishops will tell you—eagerly, for passion for the place is a characteristic of the tribe—Sewanee is also an imaginative reality of winter fog and Gothic chapels, of undergraduates and faculty in tattered gowns, of great books, enduring symphonies, and endless forests. “It’s a long way away, even from Chattanooga, in the middle of woods, on top of a bastion of mountains crenellated with blue coves,” wrote the poet-planter William Alexander Percy. “It is so beautiful that people who have once been there always, one way or another, come back. For such as can detect apple green in an evening sky, it is Arcadia—not the one that never used to be, but the one that many people always live in; only this one can be shared.”

I loved the place from the first, and love her still. I met my wife here twenty-nine years ago; my mother-in-law was the homecoming queen in 1967. Our children, born in New York City, think of Sewanee as home, which soothes my soul: At least we got that much right. For them the Fourth of July is bundled up with memories of an early morning flag-raising in Abbo’s Alley (a splendid ravine garden in the middle of campus), of a wonderful small-town parade, of fireworks by Lake Cheston. Not a bad way to think of America at her best—in fact, it may be the best way to think of America.

Aside from delicious hours of reading on a screened porch during a Tennessee thunderstorm or swimming in the reservoir behind St. Andrews-Sewanee School, an-

other quality sets these summers apart. Like you, I suspect, I spend more time than I’d care to admit consumed by the hurly-burly of political life. I’ve tried to go on the wagon for moment-to-moment news but keep falling off. Immediately.

The tradition of a Sewanee summer is the one exception. There is something about the ethos of the place—not just its aesthetics, but its values—that makes the Twitter-fueled partisan arena seem more sideshow than center stage. There’s a core Anglican sensibility to Sewanee that allows for a milieu in which one can hold divergent views and yet not become disagreeable. It was Elizabeth I who reputedly said she did not wish to make windows into men’s souls. Too many people, however, are like the pastor in the old story in which he met a friend who happened to belong to a different denomination. The pastor and his friend discussed the differences between their creeds. It was a wonderful lesson in tolerance, and, as they parted, the minister neatly summed up, remarking: “Yes, we both worship the same God, you in your way and I in His.” Well. Reason and reasonableness—Sewanee hallmarks—are the best antidote to the self-satisfaction of that apocryphal cleric.

Derived from a Shawnee word meaning “south” or “southern,” Sewanee, at its founding in 1857, represented the culmination of a nearly three-decade-old vision of James Hervey Otey, an educator and Episcopal priest, to build a church-owned university to serve the Southern states. In the context of antebellum politics and culture, the school was neither wholly nationalist nor wholly sectionalist. Otey saw the university as an undertaking in keeping with the Union; another important founder, the Louisiana bishop Leonidas Polk, would die under arms as a Confederate general.

When the war came, everything was lost. Sewanee lay in ruins. The subsequent resurrection of the university owed much not to any single Southerner but to a Connecticut native: Charles Todd Quintard, who succeeded Otey as bishop of Tennessee. Quin-tard toured England for funds—there were few resources in the post-Appomattox South—and the university opened in 1868.

Long known for a fine tradition of letters (embodied in the Sewanee Review, the nation’s oldest continuously published literary quarterly) and for its ecclesiastical connection, Sewanee has been a stronghold for the liberal arts through turmoil and tumult. The university is devoted to introducing students to what Matthew Arnold described as the best that has been thought and said in the world, in intimate classes taught only by professors.

Life in the tiny environs of Sewanee is itself an element of one’s education. As Mark Twain once wrote, if you want to know a man truly, get to know him in a village, not a city, and Sewanee is a crucible for enduring friendships not only among students but across generations. Some of our happiest experiences are spent with alumni who graduated in different decades but who seem like contemporaries. I can’t count the number of enchanting hours we’ve spent at Vaughan and Nora Frances McRae’s idyllic redoubt on the bluff. Nora Frances, who went to the college, and I never overlapped as undergraduates (we met as members of the board), but that detail has long been irrelevant. Years ago the McRaes bought an old convent house alongside the grounds of St. Mary’s,

an Episcopal nunnery, where the family’s sprawling porch is a center of summer life. That devout Methodists took over an Anglican property would have created an ecclesiastical crisis in another age. Now it just leads to cocktails. Who said progress is dead?

Such close-knit networks of kith and kin could risk breeding provincialism, but Sewanee has long transcended the geographic confines of its official name, the University of the South, to include not only the particular but the universal. You can see more from a mountain, and Sewanee’s global focus, ranging from questions of the soul to our stewardship of the physical environment, belies its relative isolation.

No matter the season, there is something irresistible about the place and its people—for, as Mr. Percy noted, we always, one way or another, come back. And some of us never really leave. Or want to.