“God creates the world and say on Saturday afternoon he must separate the animals from man so he creates a sudden chasm like an earthquake that leaves man on one side and the animals on the other. And while the chasm’s open, dog jumps over and stands by man. And that’s the way it’s gonna be. That’s the way it’s gotta be.”—Barry Hannah

Charles Thomas didn’t so much jump a chasm as crawl out from under a single-wide in Cherokee, North Carolina, in desperate need of an orthodontist. Mouth closed, his teeth protrude from all sides like some wild boar–sand tiger shark love child gooned out on methamphetamine. It’s those teeth and a mouth not fit to chew that make eating a full-time job. Every day’s the same old struggle: Grab five pieces of kibble, drop four, swallow one, over and over, till the bowl’s empty.

I live in an old white clapboard farmhouse on forty acres of pasture where the owners keep two horses and fifteen head of cattle. All his life, Charles—a.k.a. Charlie, Stinkpot, Chuck, Chuckwagon, Charlie Britches, Charles T, and Chaz—has had the run of the place. Mornings are for napping, flat on his back with his feet sprawled toward the sky. Late afternoon, he takes a soak like an old man in the horse trough. Soon as the sun’s down, he’s ready to run anything that moves—foxes, possums, coons, and twice last summer, a skunk that either loved him like Pepé Le Pew or absolutely hated my guts.

I guess Charlie’s my stepson in that I was lucky enough to fall in love with the woman who raised him. Ashley always jokes that the real reason I’m with her is because of her dog, and while that’s not entirely true, I will say I love that wiry bastard about as much as a man can love anything.

Charlie was indeed found beneath a trailer, part of a litter that was brought to an animal rescue, where he and twenty-one other puppies were set to be euthanized. A woman at the shelter put them all in a box and took it upon herself to find them homes. It was the middle of January, and Ashley was at a bonfire party and that’s where the puppies wound up. She picked Charles out of the box, primarily on account of his crooked teeth, and he slept curled against her that night in the back of her SUV. They woke the next morning with two inches of snow on the ground, each keeping the other warm, and he’s had her heart ever since.

The woman who rescued Charles from the shelter remembers his mother being a Jack Russell–beagle mix, and as a pup he carried those brown and tan markings. When I first saw him at eight years old, however, no telltale signs of breed remained. He’s pink skinned, bronze eyed, wirehaired, and tinged white, the color of heavy cream, twenty-seven pounds of questionable lineage built for slipping beneath barbed-wire fence at twenty miles an hour. Since the day Chaz and I met three years ago, the two of us have been inseparable. I walk the farm; he’s right beside me. I lie down at night; he’s a few feet away. I hop in the truck; he’s riding shotgun. Charlie holds to my heels like a shadow.

When Chaz came into my life, I was seeing a psychologist twice a week to work my way through a depression and anxiety I’ve carried since I was a kid. One of the main reasons I started going was because my life as a novelist requires that I do things outside my comfort zone. I don’t like crowds or being surrounded, because I can’t keep eyes on everyone around me. I prefer my back to the wall. I don’t like traveling to unfamiliar places, or being in a room where I don’t know the exits. I always have to have a plan to get out. For the most part, I don’t like interacting with people. Unfortunately, those traits make it hard to tear off on a book tour spanning nineteen cities in twenty-one days, so I’ve done my best to cope.

I grew up to a country people who’d been swallowed by a city. My father’s family settled in and around Charlotte, North Carolina, in the late 1700s. Most of my ancestors worked tobacco and cotton, dirt-poor sharecroppers who broke their backs to survive. When I was a kid, in the shadows of skyscrapers, my uncle still kept a kennel of hounds to run rabbit each fall. I grew up tromping across a pasture of chest-high field grass to fish a farm pond most evenings. Where I lived was a tiny holdout spot of country in an ever-expanding cityscape. Drugs and violence were just a stone’s throw away, and I found myself slap-dab in the middle of it most my life.

I was twelve or thirteen the first time I had a gun put to my head. I was in eighth grade. I was at school. The science teacher had sent me outside to find things we could look at under a microscope—dried leaves, empty snail shells, dirt clods, dead bugs. I can’t really remember what the man looked like. I think he was wearing a hooded sweatshirt. What I remember clearly is the gun. A small snub-nosed revolver. Black handle. Brushed-steel frame. A black hole that looked like it stretched on forever. He walked right up and shoved that wheel gun into my temple and what I felt in that moment has hung around my neck ever since.

Here’s the thing about trauma: No one experiences the same event in the same way. Everyone processes things differently so that the moments that impacted me most as a child might not have affected others near as severely.

For Chaz, I think the trigger event might have been being abandoned as a puppy underneath that trailer. He doesn’t like being left alone. If I’m on the road, he doesn’t eat. He doesn’t sleep. He waits anxiously, watching the spot in the driveway where my truck should be.

When Charlie was a few years old, he fell asleep underneath a pickup. The driver unknowingly ran Chaz over and crushed one of his hind legs, an injury still evident in the way that back leg slings woppyjawed every time he barrels off wide-ass open after a rabbit. As a result of that experience, though, Charles doesn’t like when folks touch his hindquarters. He’s fine if you scratch his back, but don’t reach for that leg. He gets awfully spooky around cars. Truth is he’s awfully spooky most the time.

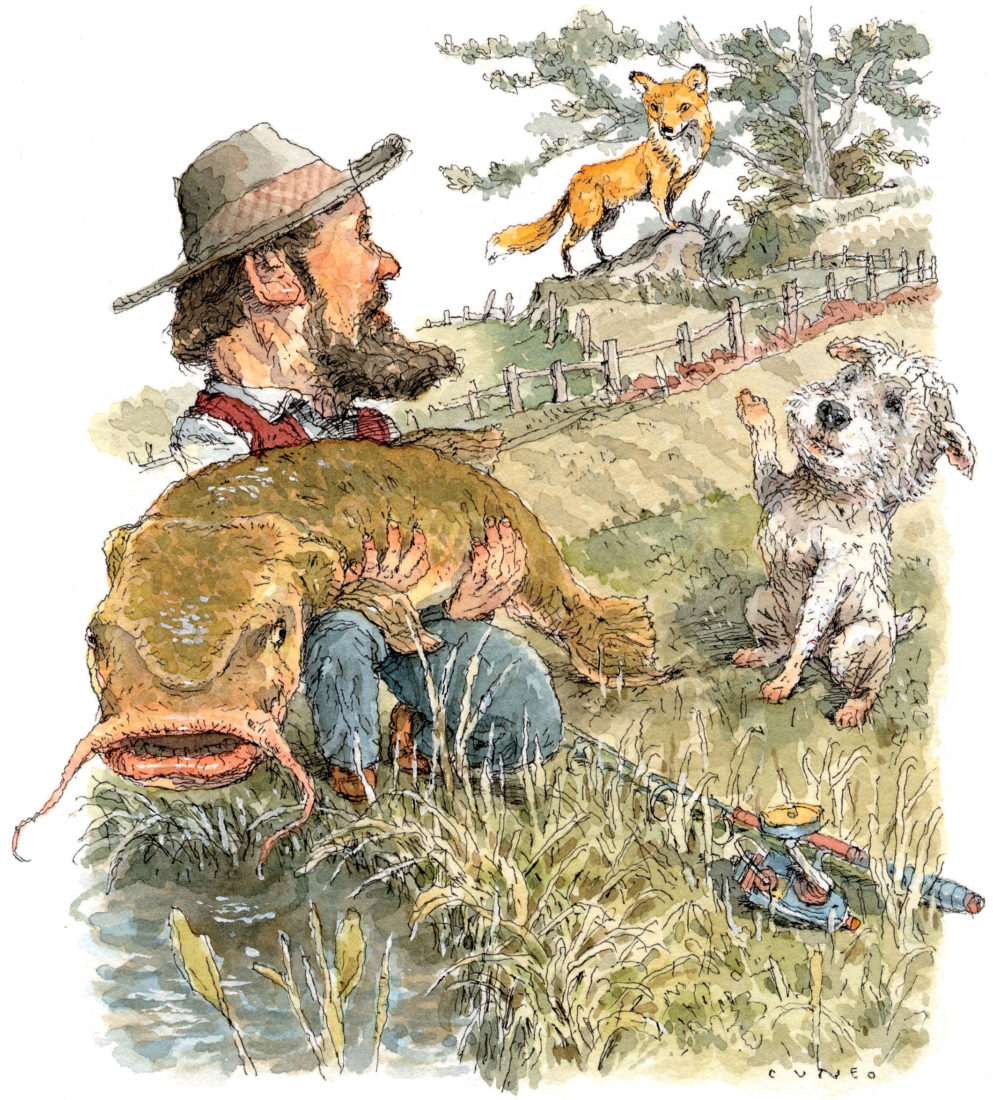

What I’m getting at is that the two of us aren’t all that different. I tell folks that Chaz and I are two peas in an anxiety-ridden pod, and I guess we’re codependents in that way. He takes me on walkabouts through the pasture where I can smell flowers, and I take him on rides to the dump where he can sniff trash. He shows me the red fox in field grass, and I show him thirty-pound flathead catfish that could eat him alive. In winter, I set my rabbit boxes by trails he uncovers nose to ground.

In the summer, I lead him to mountain streams filled with speckled trout and let him collapse along edges of current to cool off.

Loneliness is the root of the anxious heart. It’s that helpless feeling, that lack of control, that I’m-all-alone-in-this-spinning-world-and-there’s-nothing-to-stop-its-whirling sort of feeling that bears down with an unfathomable weight and holds the anxious hostage. But when I look across the cab of my truck and see Chaz with his head out the window, the wiry hairs of his beard licking about his face like the tail of a white-hot comet, I don’t feel the way I used to feel. When it’s just the two of us, everything that I once carried has been laid aside.

Looking at the relationship man has had with the natural world, the domestication of dog may be the only thing we ever got right. Scientists don’t agree on when and how it happened. Some say as far back as thirty thousand years ago, others say ten thousand. Some argue there was a single event, all dogs following a solitary lineage, while others argue multiple events occurred, various groups of wolves becoming domesticated by different people in different places. However it happened, the greatest truth to come from that moment is what I know every time Chaz rams his dirty face into the side of my leg and offers up that crooked-toothed smile. Ever since dog jumped the chasm and stood at our side, this has been the gift given by dog to man, a gift that, when we’re lucky, we can return: Never again must we be alone.