The story of the Loveless Cafe begins with crispy fried chicken and scratch-made buttermilk biscuits served hot from the front stoop of Annie and Lon Loveless’s pre-war cottage on Tennessee’s Highway 100, just outside Nashville. As the couple’s reputation grew among hungry midcentury travelers headed south on the Natchez Trace Parkway or west from Nashville to Memphis—in 1951, Highway 100 was the only road connecting the two Tennessee metros—so did the business.

To meet the demand for Annie’s comfort classics, the couple converted their modest home into a full-service café. They added picnic tables out front as well as a fourteen-room motel and a smokehouse, where Lon began curing their now-famous country hams. Among the throngs of early travelers they attracted was a man named Kellie Reeder, a general store owner in nearby Dibrell, Tennessee, who frequently made the hour-and-a-half trip to Nashville to meet with his suppliers. “Kellie discovered Loveless in 1960,” says his son-in-law Tommy Oliphant. He was so impressed by the café that he eventually persuaded his entire family to make the trip—for Easter dinner no less.

“That first Easter dinner, in 1963, it was just me and my wife, Cynthia, her mother and father, and her brother Glen and his wife, Ernestine,” Oliphant says. “Loveless was just a small house at the time. And so they sat us in our own little room.” Kellie passed away just a few years later in 1965—before Tommy and Cynthia’s first child was born—but the Easter dinner tradition he started lives on, an annual fixture in the lives of the grandchildren and great-grandchildren he never got the chance to meet.

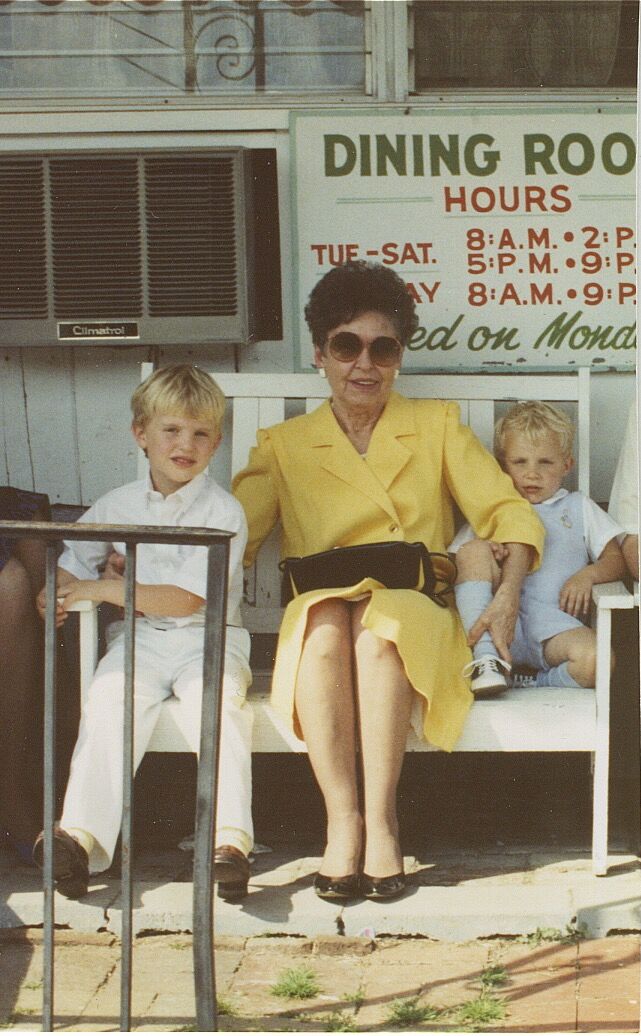

Sixty years later, his family hasn’t missed a single Easter at Loveless. “As our family grew, there were eventually so many of us packed into that original little room that when the staff served us food and drinks, the servers had to come to the door and hand plates to the closest person,” Oliphant recalls. “We’d pass them the rest of the way.” Year after year, down the line, the group passed plates of breakfast and brunch standards, including large platters of those signature buttermilk biscuits, which later became the singular domain of the late Carol Fay Ellison, dubbed the “Biscuit Lady” by staff and regulars like the Oliphants.

And when crowded gatherings became verboten—and the restaurant temporarily shuttered—in the early days of the pandemic, the Loveless staff ensured the family’s decades-long dining streak remained unbroken. “They delivered a huge box of food right to our door on Easter,” Oliphant says.

Today, more than two-dozen family members travel from all over the South to break biscuits together at the restaurant on Easter Sunday. There’s even a family biscuit eating contest. What’s the record? “Enough to be embarrassed about,” Oliphant says with a laugh. “Even the babies love ’em.” Over the years, the various Loveless owners, waitstaff, and managers became unofficial Oliphants. “It’s really no longer Loveless Cafe to us,” he says. “It’s all just family.”

In the last six decades, Nashville and the surrounding area has exploded. The landmark restaurant has matched pace and now includes two event spaces, a food truck, a handful of shops, and a commercial kitchen that ships Loveless staples, like the famed biscuits and homemade preserves, all over the country. And though the café serves nearly half a million guests each year, the Southern comfort food and old-fashioned hospitality that first drew Kellie Reeder to the Loveless dining room endure—just like the Oliphant Easter tradition.

“It’s amazing how this family has stuck together all these years with this tradition. People die and people are born, but it just carries right on,” Oliphant says. This Easter will mark the first gathering without Oliphant’s wife, Cynthia, who passed away last fall. “When Cynthia passed away, the Loveless staff sent a huge arrangement of fresh cut flowers—my wife was a flower girl. She loved them. That’s why I say Loveless is not just a restaurant. It’s family.”