“I never wanted to be a professional Southerner,” says the author Rick Bragg, who could perhaps most easily be described as a professional Southerner. “But at the same time, I’ve never been more proud to be anything but a Southern writer.” And that he is—Bragg, a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist, the author of nonfiction books including All Over But the Shoutin’, and a Garden & Gun contributor, largely explores his life in the rural South in his work.

Today, he releases a new collection of essays, Where I Come From: Stories from the Deep South. A cancer survivor, Bragg has been spending most of this year isolating at home in Alabama with his mother. The book editors he works with told him this collection would be a welcome balm for readers during a difficult year. “I hope that everyone’s right and that it does give people a breath,” he says. “I think we need one. I know that for me, reading the people who write down here has served to help pass the time, if not quicker, then it gives something of value to fill up that time.”

We chatted with the author about what he’s been cooking, reading, and watching lately, and about the book he’s working on next. Spoiler: It’s about his dog.

Sounds like you’re driving. How are you?

I’m still old and still tired and still grouchy. [Laughs.]

Not sure if you can hear her breathing over the phone…but you basically just described the old bulldog I just adopted who is sitting next to me.

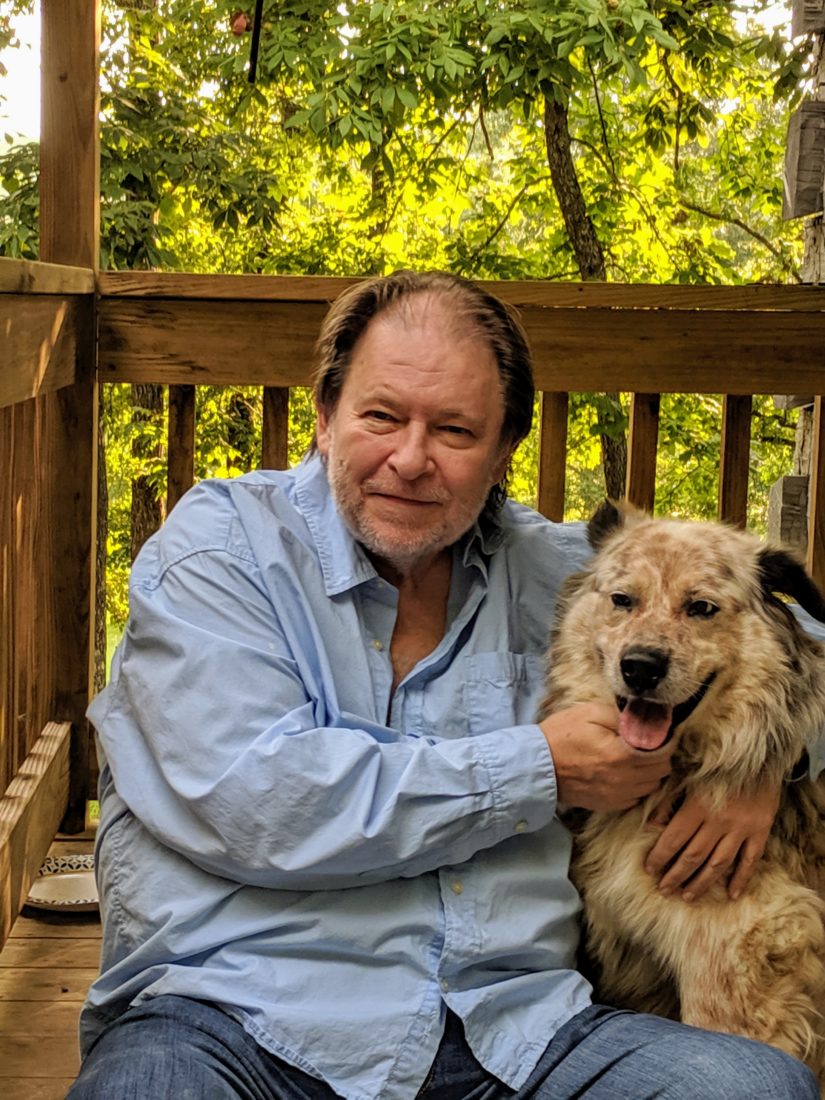

If you’ve got a bulldog and it’s not grouchy, then I think you’ve got an inferior bulldog. If you want a happy dog, get you a golden. I’ve got an illegitimate Australian shepherd and he is equal parts brilliant and utter stupidity. He can herd anything from a milk jug to a flock of birds, but he doesn’t take them anywhere special.

What do you mean he’s illegitimate?

His daddy was a traveling man. I found him on a ridge line behind the house and he was just starving to death. He had been tore up in a dog fight, so he was probably going to die. I knew it was a bad idea, but I went out there and got him. That was three years ago, and I wrote a book for Knopf that will appear next fall on the whole experience. Because if he was going to make me suffer through having him, I was going to write about it. His name is Speck, short for the Speckled Beauty because he’s got freckles, those copper points. My mom called him Speck and it stuck. He’s my boy. He’s a terrible dog, but he’s the best dog in the world. (Bragg wrote about his dogs Speck, Skinny, and Puppy for G&G here.)

You’ve called your mom the Best Cook in the World. How did she react to that title?

She says, “I wasn’t even the best cook on my road.” She thinks that everybody of her generation was a great cook. I grew up on her food, and it’s probably one reason I need so many doctors now. But if there is a better cook, I don’t know them.

Do you cook?

I’m not a great cook, but I can cook some things. I can make quite a chili. I’m good with beans. I’m good with breakfast. I make probably the unhealthiest scrambled eggs in history. Cook them in butter, add a little American cheese, it just melts so much better than cheddar and it gives them a smoother taste. Then Mom will make a pan of biscuits. I still can’t make a biscuit. And we love a good pork product where I come from, so I’ll fry some bacon.

After that, what’s a day of meals look like for you two?

We’ll have some sliced tomatoes or some cantaloupe. Lunch time is usually my chance to get out of the house. We live in the middle of forty acres of mountain pasture, so it can be a little quiet sometimes. The closest small town is Jacksonville, Alabama, and before COVID, that was my escape—I would go eat lunch and sit and think or read a newspaper back when you could still find one.

My mother loves to cook a noon meal, it’s like the big meal of the day—that’s the way Southerners used to do it. She’ll cook pinto beans, fried cabbage, one of my favorite things—you can call it stewed cabbage if you want to be politically correct, but it’s fried cabbage. Cornbread, stewed squash, and even in winter she tries to have something cold like sliced tomatoes, cucumber, sliced onion, and a lot of chow chow or relish. You could call it a vegetarian meal except for the fact that everything’s got a hunk of pork in it.

Sometimes after that big noon meal, you’ll put a lid on the pot and have it for supper and believe me, you don’t mind leftovers if they’re good leftovers. Potato salad’s just as good the third time around. But my sister-in-law and my brother come every evening, and sometimes she will cook things from this century—crowder peas, chicken breasts, spaghetti, vegetable soup. Sometimes, this isn’t my favorite, but my brother Sam and my mom will just have hot cornbread and cold buttermilk crumbled up together with onion, relish, or hot pepper.

To be honest, like everybody else who is in old age, I’m having to be more careful now. And you know Southerners, you can’t trust us with a salad. If you give us a salad, there’s gonna be some cheese on it or some Thousand Island. We just can’t be trusted with a salad. I love bacon bits, I even love the fake ones, the kind you think are probably made out of Blue Horse notebook paper, just kind of crisped up.

LISTEN: RICK BRAGG ON G&G’S WHOLE HOG PODCAST

How else have you been spending your time?

I’ve been working on this book about the dog, and I went back and reread books that I loved when I was a boy. I reread Old Yeller and Savage Sam by Fred Gipson, which is the book that made me think when I was a kid, oh I can do this, I can write a story about a dog. I read some Jack London because my dog is kind of a poor-white-trash version of his Buck that he wrote about, and I recently read a James Lee Burke novel called Black Cherry Blues.

James Lee Burke said recently that he’s been watching a lot of Westerns. Do you watch Westerns too?

I’ve watched Red River four times since COVID started. Sure, with Westerns, there’s a silliness, the cavalry and soldiers singing along as they ride through the gritty dessert. But anybody who’s ever seen Red River and says they don’t like it, I would question their character. It’s the tall man on a horse thing—it’s nice to believe in a time of crisis that there’s still a cavalry and it don’t matter if they are singing a stupid song.

I watched all of the Longmire series, a series that was smarter than the usual modern-day Westerns. There’s one mystery after another, and you start watching and realize you haven’t got up in four hours. I watched Moby Dick for the 533rd time with Gregory Peck. I watched Lonesome Dove, the TV series with Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones, for the seventeenth time.

How have you been thinking about time?

I don’t mind spouting an opinion, but I’m the worst human I can think of to suggest that I know how to spend time. All I know is the old cliché: One day you will wake up and you don’t know where it all went. The thing that’s worse is knowing exactly where it all went. Waking up and knowing that there wasn’t enough of the sweeter things. And I’ve had a good life by any standard, but I also had some things I had to do. I kind of lived from book contract to book contract, deadline to deadline, and I don’t know if this is the end of my life—I hope not—but I have things I have to take care of. Like my mom. That’s not a question.

If I were talking to someone about avoiding regret, which is really what it gets down to when it’s all over with, I would keep my mouth shut. Because I don’t know how. But I do know this, and this is a much deeper answer than I thought I’d be giving while driving right now, but wishing that things would go different in life is so foolish, because that would be wishing you were a different human. I was going to do what I was going to do in the way I did it, and if I had it all to do over again, I would probably do the same damn thing.

Do the best you can. Try to get through life without making a bigger mess than you already made and try to celebrate the things you did right.

What you aspire to is peace of mind. I’ve always thought a good life would be—and I’m not making this up—taking a lawn chair down to the pond, taking a fishing rod and a cooler full of bologna sandwiches, and, that late in life, you can drink anything you want to. I would get me a Coca-Cola or a Barq’s root beer, and I would take a Browning .22 pistol. I would sit there in that chair and pretend to fish. I would not actually fish and I would shoot water moccasins. I’d just sit there and shoot snakes. And I realize that a lot of people, a lot of herpetologists, would think that’s a terrible thing, but water moccasins don’t have a lot of redeeming values. They eat frogs. What did a frog ever hurt? I would sit there and shoot water moccasins and drink root beer and try not to think about my regrets.

This new book of essays will have stories like that?

As I write in the introduction, I think the pieces remember the best part of us, our food, our music, our customs, our traditions, and our language and even sometimes our foibles and our faux pas and our being a little outta step sometimes in a way that doesn’t hurt anyone. Like the fact that my smart phone can’t understand my accent. So I think this book is well timed—at least that’s what everyone keeps telling me.

We picked the essays that could help form a theme. Seemed like a book like this might give people a little breath. There’s a section on Halloween, a section on Christmas and Thanksgiving, a story about shaking jellied cranberry sauce outta a can. There’s a story in there about the fact that I am the worst fisherman in the world. There’s a story about Tupperware and what happened to going to a family reunion and having everything there in Tupperware, from baked beans to potato salad to fried chicken sweating on top of a clean dish towel. There’s a lot of nostalgia in it.

Nostalgia—it’s not a sweet and fleeting thing. I think it’s a power. Nostalgia shapes so much of what we do, and if it’s a good nostalgia, a sweet nostalgia and a gentle one, then maybe that shapes an opinion. If all you do is sit around and wish you could turn the clock back to the mean old days, then that might shape how you behave now too. I’ve never wanted to turn the clock back, but there is nothing wrong with remembering the finer part of our nature.

Tell us a Halloween memory—what was your best costume as a kid?

I went as a ghost one year and that involved cutting two holes in a pillowcase that had already been used as a rag. Bless their hearts, these people who can sew anything, they can never get the eye holes right. So not only are you a ghost, but you’re a cyclops. One eye hole is around your ear, and the last thing your mother says is “Don’t step in front of any cars!” And you say, “You oughta thought about that before you cut the eye holes.”

The thing I loved about Halloween more than anything was those damn Day-Glo orange plastic pumpkins. There’s something so cheerful about them, something so amazingly happy. You can’t go trick-or-treating in the country, the houses are too far apart and you’ve got dogs to contend with. So you go to town, to a gentler place, and one of the college professors would put out whole, full-size Hershey bars. I mean that’s generosity.

Plans for Halloween this year?

I’m sixty-one years old, and I can go get a Hershey bar now if I want one. I will play a kind of roulette with the cable TV, and I will try to find the black-and-white horror movies from the forties and fifties. I like the ones where the spaceships kind of wobble down on a string because the special effects are not what they should be. Like that one about the giant octopus who tried to eat San Francisco, or the old Dracula or old werewolf movies. If you want to see a really genuinely scary, bizarre black-and-white horror movie, watch The Invisible Man with Claude Rains. I mean that’s spooky. And I’ll try not to eat that second Hershey bar.

Ok, lightning round: biscuits or cornbread?

See, you can’t—that’s an impossible question. I probably eat more cornbread because it’s the loaf of French bread of the South. But it depends on the accoutrement. If you’re going to have pinto beans and ham or coleslaw and potato salad, then you’re gonna have to have cornbread, that’s no doubt. Yet if it is fried chicken and navy beans, then biscuits. That’s an impossible question. That’ll make your head hurt.

What’s bringing you hope?

My stepson Jake is getting his PhD at the University of Virginia. He has worked brutally hard to make his way in the world. This is a kid who didn’t have to want for anything. But he did so much on his own. He’s studying blue-collar workers, because he sees value in their lives. The way that he looks at the world, with that happiness and optimism, that’s the best you can hope for.

Something that’s made you laugh lately?

Getting out of bed should be a reasonably danger-free experience. I had kicked a pillow to the floor at some point while I was fighting all those demons that come to get you in the middle of the night. And my foot landed on that pillow, which took off like a sled across the floor. I landed so hard on my chin and my chest and stomach that it actually hurt my shoulder on the backside. So I’m laying there on the floor and I did not immediately get back up, not because I couldn’t, but I thought, If I stay down here, it is impossible to fall again. No one has ever invented a way to fall once onto a solid flat surface and then fall again. So I just stayed there awhile. I was comfortable except for the pain, and I already had the pillow.

Who are some Southern authors who you think should get more attention?

There are five or six young ones out there coming up…There is such a wealth of talent down here.

The ones that I grew up around have already got such great attention: Who writes better about tragedy than Charles Frazier and Ron Rash? And until I read Larry McMurtry, I never knew that you could make a character get up and walk and talk and come to life. I never knew how profound a sentence fragment could be until I read The Last Picture Show. Pat Conroy was so good to me, he was so elegant. And James Lee Burke can describe the same sunset over and over again and make you see it completely differently each time. There’s a passage from Jolie Blon’s Bounce where he is writing about a juke joint, when the neon light blazes, and how in the daytime it all fades and these places become invisible. I mean, who writes better? There’s an embarrassment of writing riches down here. It seems like a cliché that it’s in the dirt—it’s in the weeds.