Arts & Culture

The Dog That Stole Rick Bragg’s Heart

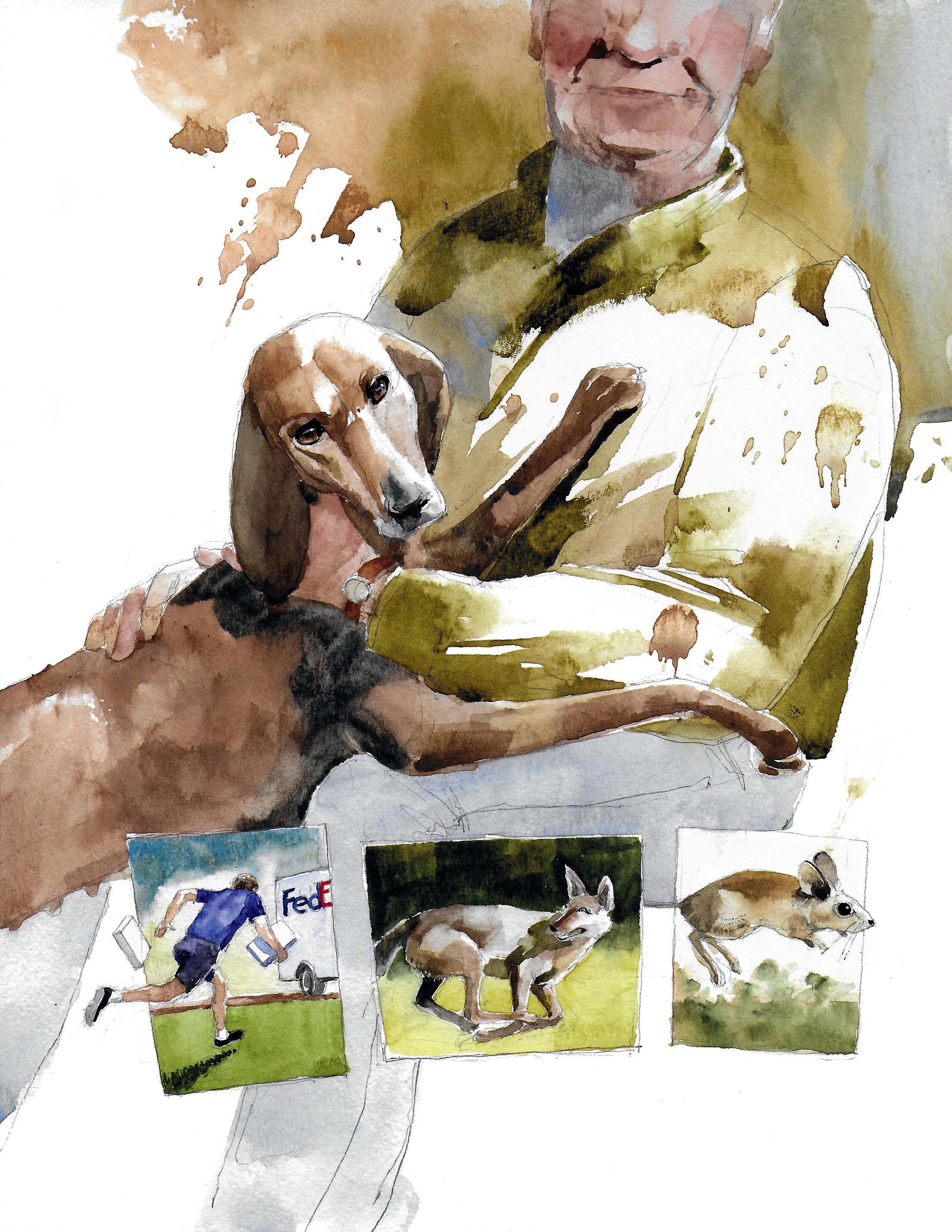

She was two dogs high, half a dog wide, and the only animal to ever run away with an Alabama author’s heart

Illustration: Stan fellows

It rained every day for three months, from late fall till spring. I’m sure a weak sun came out once or twice but never long enough to get used to. Mostly it was dank and cold, and the sky was low, like the ceiling of a coal mine, the clouds the color of asphalt. By March the low places ran with muddy water and washed whole lifetimes away, and storms tore up some parts of the South like they were held together with shoeboxes and glue. Things rusted that never had, doors swelled and jammed, and roots of hundred-year-old trees lost their grip in the liquid soil and fell under their own weight. It even caused a kind of moldering in the mind, an absence of optimism, like we had tracked the red mud into our finer nature. I have often heard old people in Alabama pray for rain, but never so hard against it. My mother began to see it as a sign, and it did seem odd, as the weeks slogged by. The weatherman offered no hope, night after night; he might as well have been a cardboard cutout with a fixed, final forecast, and the rains fell, till the end of the world.

Or it might be it all just seemed that way, on the day a good dog died.

The people who discarded her, who threw her away, called her something else, but we never knew that name. We called her Skinny, because she was two dogs high and half a dog wide. She was so lean, so long-legged and light, she seemed to glide without effort or even the pull of gravity when she flashed through the pines and the rocky places up high, running down a deer or just some distant sound, and she would sprint across a mountain to make sure a scent on the breeze presented no threat to her people, her porch, her place. She was just a stray that walked up one day in the yard, part redbone, foxhound, and a dozen other bloods, an old-fashioned, outside, Alabama brown dog that survived abandonment and starvation and bloody battles with coons and coyotes and wild dogs. We fed her and so she became part of the place, for seven years or more, till the hateful combination of a rare tick-borne disease and pneumonia—I blamed the constant cold and damp for that—finally killed her, early on a Sunday afternoon.

We never knew her age, either, but believe she was about eight or so when she died, with us long enough to get used to, to root out a place in our minds. I have never prayed a lot and, frankly, as a prolific, almost redundant sinner, have seldom asked for or expected help from on high. But as the nice, sad lady at the vet’s office handed her to me, covered in a Winnie the Pooh blanket, topped with her empty collar, I cynically wondered, Well, Lord, do you reckon you could stop the rain long enough to let us get her in the ground?

But I guess you don’t stand much of a chance with the Creator when you ask for something as a smart aleck, and it rained all day, again. My brother Sam and I took a mattock and two shovels into a corner of the pasture and hacked through the vines and privet bushes to a dormant orchard of old peach, apple, and plum trees. There, next to a beautiful German shepherd we called Pretty Girl and a goat with no name, we mucked out her grave. It seemed a miserable place, in the gloom, but not if you had seen Skinny before, in the sunshine. She had gone into the vines and thorns of the tangled orchard after big rabbits every day of her new life. She treed a million squirrels and kept one poor possum hostage in a wild plum tree for what seemed like the better part of a year. She was a hound, and so believed it was her prerogative to hunt and hunt everything, even tracking the flight of a timber wasp or a falling leaf, and the fact that she did not differentiate a raccoon from the FedEx man should not be held against her, in the story of her life. My point is, she was something special in motion, running that mountain, and maybe this old pet cemetery was not such a bad place for a dog to lie, here in a tangle where the fat rabbits thumped around over your bones.

Even in the muck it had been hard-digging, because of the roots, and, being old men, we took a while to get straightened up good when we were through. We looked at each other when we did, a little confused about what to do next. It seemed like something needed to be said over her, but there was enough of the lingering Pentecostal left in us to prevent it. The foot washers don’t pray for dogs, for there is no soul in them, or so we had always been told. Dogs are creatures of this world alone, and this was the end of her. So we just stood, leaning on our shovels as we had when we were boys, and let the rain soak us to the bone.

“Well,” said my brother, finally, “she was a good dog.”

We could, both of us, risk that much hell. We slid the tools into the back of the pickup and rode through the waterlogged pasture half-expecting to mire up to the axle, and as we inched through the spongy grass, I thought about how it was that almost all dog stories are the same, how they begin and end the same, a trajectory as sure as death, as sorrow. And then you move on, to a new arc, a new story, and another short life. Our place, in the Appalachian foothills, had always been a magnet for strays, for discarded dogs, so we usually got them for only part of their lives, and an even shorter arc. But this death, this story, was different somehow, and struck me harder, as if her place in the longer journey, the arc of the people she watched over with almost human, intelligent eyes, would not so easily fade.

That would come to be, as the months tumbled by. At first there was only this empty place in the landscape, a bleak quiet and a stillness so disproportionate for such a small animal, a thing so bad you knew it just had to give, because no one grieved for a dog like this. And the funny thing was, she wasn’t even my dog.

I don’t know who threw her away, but he was a son of a bitch, whoever he was. She had been a living skeleton when she came over the ridgeline and just sat there, patient, starving, watching the house below and the people who came and went. It was clear she had doffed a litter of pups in the past few weeks, somewhere, but though we searched we could not find them; from the look of her, they must have perished in the woods, but I guess we’ll never know that, either. She came down only when we called. My mother made her a skillet of water gravy and fed her half a pone of cold cornbread, and she became a part of us, or maybe it is more accurate to say she took possession of the place, of the pastures, the mountain, and the humans on it. It would be foolish to say she belonged to us. Skinny did not belong to anyone, really.

She tolerated and looked over the livestock, which she seemed to regard as dumb beasts fit only for keeping the grass gnawed down, and sometimes she seemed to look at two-legged beings in the same way. Strange humans were to be distrusted and chased away with strong bluffs and barks, because she never bit a soul. But it was clear, quickly, that we were hers, and she asked for and received just enough petting from her humans to remind her that she was the dog, and then she would turn away and go do something important.

From the first week, she began to protect us, haranguing the meterman, distant kinfolk, a suspicious chipmunk, the hopelessly lost Papa John’s driver, and the occasional wandering Jehovah’s Witness. Her philosophy seemed to be: Growl at ’em all, chase ’em all a quarter mile at least, and let God sort ’em out. And sometimes, purely by the law of averages, she found a proper villain this way.

Before Skinny arrived, a gray fox, well fed and as big as a Labrador, had killed every living thing on the mountain it could catch. It killed every chicken my mother had, and her ducks and ducklings, and even ran down a cat every now and then. Then it would sit halfway up the ridgeline, so close my mother could see it through her back windows, and sing to her, mocking. It was such an eerily human, menacing thing that my mother named it: Henry. She had never met a Henry she could bear, and this one was no different. It may sound like hyperbole, if you are not an old woman in a dark house cut into a mountainside.

Skinny, as soon as she could stand without trembling, put Henry on the run, and when he came back, she did it again, and again, and again. She never caught Henry, not that we are sure of, but she harassed him so long and so completely that he abandoned his honey hole on Mark Green Road and vanished into memory. My mother thinks she can hear him even now, singing, but so very faint, as if he knows where the property line is, and remembers, somehow, that a skinny dog used to roam here, and might still.

Skinny stalked the coyotes, a new menace that had just appeared, like wraiths, in the pasture with my mother’s tiny Sicilian donkeys. She burst into their midst, snapping and howling, fearless, and scattered them. They left this place as if they had never been, though, and in the spirit of Henry, sometimes we heard them in the far distance, wailing. Skinny did the same with the wild dogs that roamed through here, but they were slower to run, and she earned some scars, including a thin, black line against her fine face.

Skinny never, ever came in the house, and slept up high, on the seat of the old Yanmar tractor, where she could look down upon the land and the livestock that were in her charge. But now and then, on a cold night, she would travel to the far end of the property, where she had learned to open the front door of my little brother’s house. She would come in, invited or not, and crawl up on the foot of the bed, and sleep till about an hour before dawn, then come back across the ridgeline for biscuits at my mother’s house. “I called her January,” said my little brother, Mark, because she only appeared to him in the cold.

But for a long time, there seemed no joy in her; she seldom played much, for a young dog, and if you threw a stick or a ball, she would just look at you, as if you were numb between the ears. It took years for that to change, but it did. She would follow the familiar cars and trucks up the drive, and when you opened the door, she would place both paws on the running board and peer inside, until you spoke to her or petted her. Of course, it being Skinny, it might have been just another kind of surveillance, a trick she was playing on us, to make sure we were not trying to sneak something past her, into her yard, onto her mountain.

Illustration: Stan fellows

Finally, in the last two years of her life, she started acting like a dog. The thing I remember most is the odd way she would greet me, whenever I—or anyone she recognized—stepped from the car. She would go suddenly and completely silly, and would hop across the driveway, one paw stuck straight out as if she were pointing, and sometimes she would dance on her back legs, if only for a second or two, then go back to being her serious and intelligent self. But it was too late. I caught her dancing, caught her being glad to be alive.

She did not seem to mind being the only dog on the place. But people are a low species, compared with dogs, and so were certain to clutter up her perfect isolation sooner or later.

First, it was Puppy who came, a small mixed-breed feist, beagle, and Lord knows. He had lived the first two years of his life utterly ignored inside a chain-link fence, fed and watered but never petted or even spoken to. Puppy appeared in the yard as a kind of canine basket case, scared of everything, and when I tried to pick him up and put a collar on him, he tried to eat my face. I was afraid Skinny would not tolerate him, would run him off, but I swear she seemed to understand that he was a damaged creature, and so chose to ignore him, and even let him trail behind her, at a distance, when she ran the land. I have always been suspicious of people who tried to imbue some kind of magic on their dogs, and I am saying this is so, here. I just think her instincts were both fierce and kind, and if that is not a good dog, I don’t know what one looks like. Puppy seemed destined for a life of woe, without even a real name, but after he found a home here—and Skinny’s acceptance—I tried again to put a collar on him, and he tried again to eat my face. I named him McGraw, after the cartoon character Quick Draw McGraw, and had it stamped on his collar, which, five years later, still hangs from a nail in the garage.

Then, it was Speck, my dog. He had been the alpha in a pack of wild dogs, till he was replaced, violently, and run off to starve. I fed him after I saw him waiting, watching from the ridge, a beautiful long-haired dog that was part Australian shepherd, red heeler, and blue heeler, with a striking spotted face, but discarded, I believe, because he was blind in one eye. He ate, warily, then, fortified, ran away to fight his way back into the pack. They tore him up badly this time.

The next day I found him on the driveway in a puddle of blood, and he let me pick him up and take him to the vet, who glued and stitched him back together, though it took a while for his left ear to lay right against his head. He, like Skinny, believed he was responsible for patrolling the land, but he, unlike Skinny, was as dumb as a damn turnip, and mostly spent his days harassing the thousand-pound mule, which could have kicked him to death at any second. But he was glued to me, when he was not antagonizing the equines or trying to herd my eighty-two-year-old mother across the yard. I named him Speck, after the girlfriend of a long-ago distant cousin. The young woman had so many freckles that my grandfather named her the Speckled Beauty, and there are worse ways to name a dog, I suppose. Unlike Skinny, Speck, once he had rediscovered people, needed people, needed them badly. In some ways, in a time when my own health failed for a bit, I needed a dog of my own, but that, as we used to like to say in this business, is another story.

Skinny responded to Speck with growls, and whipped him, three or four times, across the yard. She would look at me accusingly as if to say, I will never forgive you for bringing this stupid creature into my realm, but mostly she ignored him. Sometimes I would catch her just watching him, especially when he was barking furiously in the face of the mule, in the same way, as children, we used to watch reruns of The Three Stooges.

Now and then, she let them both run with her, almost as if she were teaching them, and they would all flash through those trees, Skinny determined, the others stupidly joyful, and it was such a beautiful thing. And my mother would see me watching, because little happens here that that old woman, even mostly blind now, does not see.

“What you lookin’ at?” she asked.

“Just the dogs,” I said.

Just the Dancing Skinny, and the Speckled Beauty, and the Puppy McGraw.

I guess the other dogs missed her, when she was gone. The truth is I am not sure either one of them was smart enough to miss anything except maybe supper. They, too, challenged every car that came up the drive, though McGraw was a timid and trembling boy who tried to keep a half acre between him and any threat, and Speck could not see well enough, on one side, to make out much of anything. He was fearless, though, as Skinny had been, if a little suicidal. He still accosted the massive mule, which just regarded him with a kind of bewilderment. He wanted to herd it, and it did not want to be herded, but I guess he forgot that every night when he went to sleep, and went down the hill to the pasture every single day, expecting a different result. A head doctor in Birmingham told me that is what mental illness is, but I do not know if it applies to dogs. My point is, you just naturally miss a smart dog, and the things they do.

In time my grief did give, not because I forgot Skinny or replaced her, but because I found that it was not so hurtful, in time, to remember. I would see the goofy Speck running wide open between the trees, and, I swear, I could see that skinny brown dog running ahead. It is still awful, that absence, but it is easier to recall the times before, and now and then my brothers and I will even say, “Hey, you remember when ol’ Skinny…” and sometimes the memory makes you sick at heart and sometimes it just resurrects a good dog, for a little while. I don’t know if dogs go to heaven or not; a human lifetime, the arc of it, may be the closest to eternity that dogs will come, at least as long as you remember them.

The thing that haunts me is my second-to-last visit to the vet, when the people there tried to save her life, and I went to see her. She came out of her crate and stood as I petted her, and then, being a smart dog, just turned and went back into her cage without being told, as if she gave up, as if she knew. That is foolish, of course. No dogs are that smart, are they?

I know, if the arc of my life continues for any time at all, I don’t want a smart dog again.

But then, she wasn’t my dog.