In 1976, Jimmy Carter stood behind the podium I at the Democratic National Convention in New York City and put forth a message of hope to a country still reeling from the effects of Watergate, Richard Nixon’s resignation, and the Vietnam War. “I have never had more faith in America than I do today,” he said. “We have an America that, in Bob Dylan’s phrase, is busy being born, not busy dying.”

Politicians don’t typically quote rock stars, but dropping Dylan’s name in front of a nationwide audience was perfectly in line with Carter, who not only admired musicians but also considered some of them close friends, including Dylan, Willie Nelson, and Gregg Allman. Those ties are at the center of the poignant new documentary Jimmy Carter Rock & Roll President (airing in January on CNN and available for streaming now), a touching love letter that explores how musicians played a key role in getting a peanut farmer from South Georgia into the White House, as well as Carter’s belief in the power of music to bring people together and create change.

That the story is told by two natives of the South makes it even more impactful. Director Mary Wharton—who won a Grammy in 2004 for Sam Cooke: Legend, a documentary on the soul singer—hails from Tallahassee, Florida, and producer Chris Farrell grew up in Jacksonville. Both had bohemian childhoods. Wharton’s father, who worked on the Carter film’s score, is a musician (known in the North Florida music scene as the Sauce Boss for his side gig of making homemade hot sauce), and Farrell’s mother was a social worker and civil rights activist who married a Black man when Farrell was a child in the early seventies. “Growing up in the South at that time was difficult,” Farrell says. “But Mary and I shared the same Southern sensibility that continues to this day.”

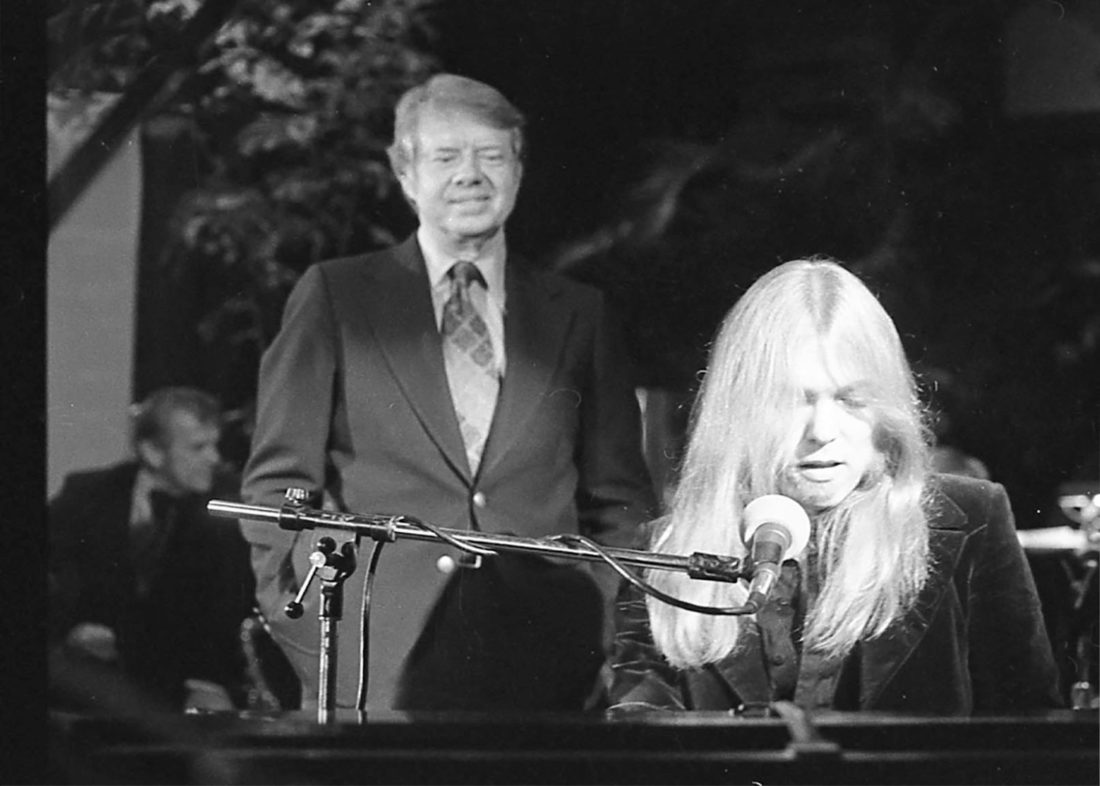

Documentaries are frequently passion projects. They can take years to make, with often shaky financing. Rock & Roll President was no different, and compounding those headaches, Farrell was a first-time film producer. “I had no idea what I was doing,” he says with a laugh. “People who do this for a living told me, ‘Never put in your own money.’ But nobody knew who I was, so of course I did.” Originally, Farrell had met with some Atlanta businessmen about trying to make an Allman Brothers documentary, and one of the potential bankrollers, Todd Smith, began telling him stories about Carter and his relationship with the Allmans, who befriended him when he was governor of Georgia (replacing staunch segregationist Lester Maddox) and held fundraising concerts during his presidential campaign. As Carter says in the film, “The Allman Brothers helped put me in the White House by raising money when I didn’t have any money.”

Farrell walked out of the meeting knowing that there was more to tell about Carter’s love of music. “This story was hiding in plain sight,” he says. “No one had done the legwork. President Carter’s knowledge of music is incredible: jazz, country, gospel. And it’s authentic. He didn’t use music as a political ploy to get the young vote.”

Carter himself ended up sitting for two hour-long sessions at his home in Plains, Georgia, and at the Carter Center in Atlanta, and the film deftly weaves his words with footage from his time in Georgia politics all the way through his presidency. It also includes original interviews with Dylan (no small task securing that), Nelson, Rosanne Cash, Nile Rodgers, Garth Brooks, Trisha Yearwood, Chuck Leavell, and even Bono of U2, who was inspired by Carter during the band’s formative days in Ireland.

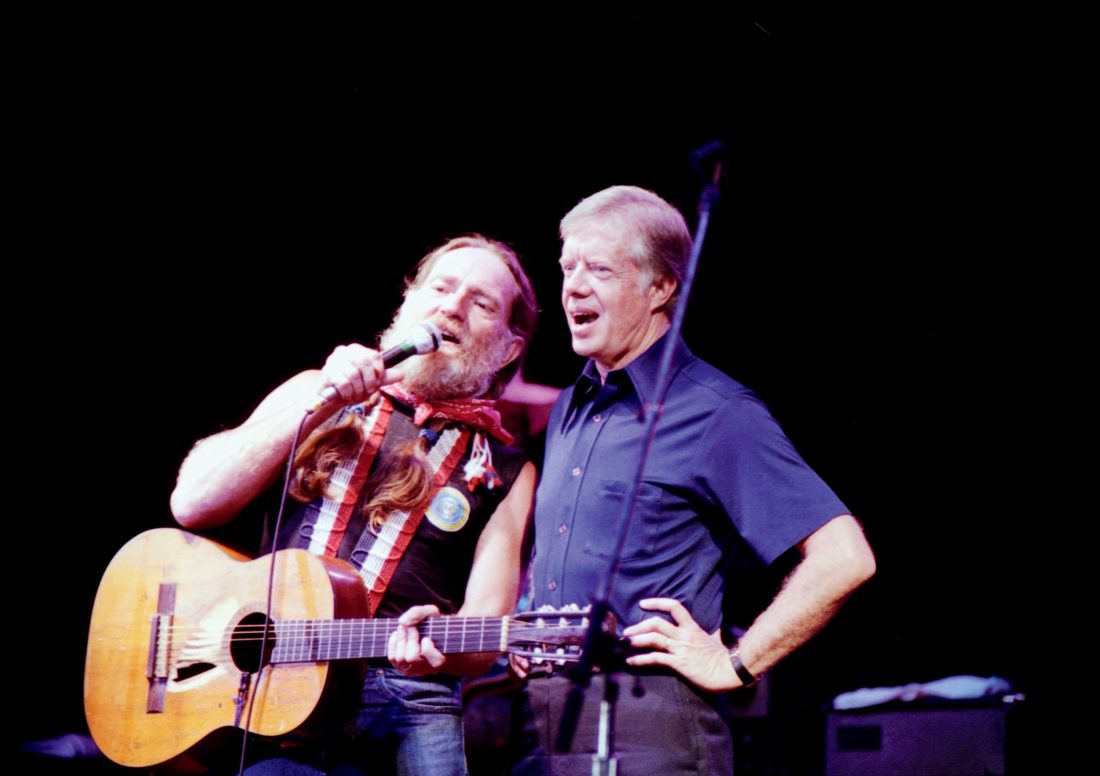

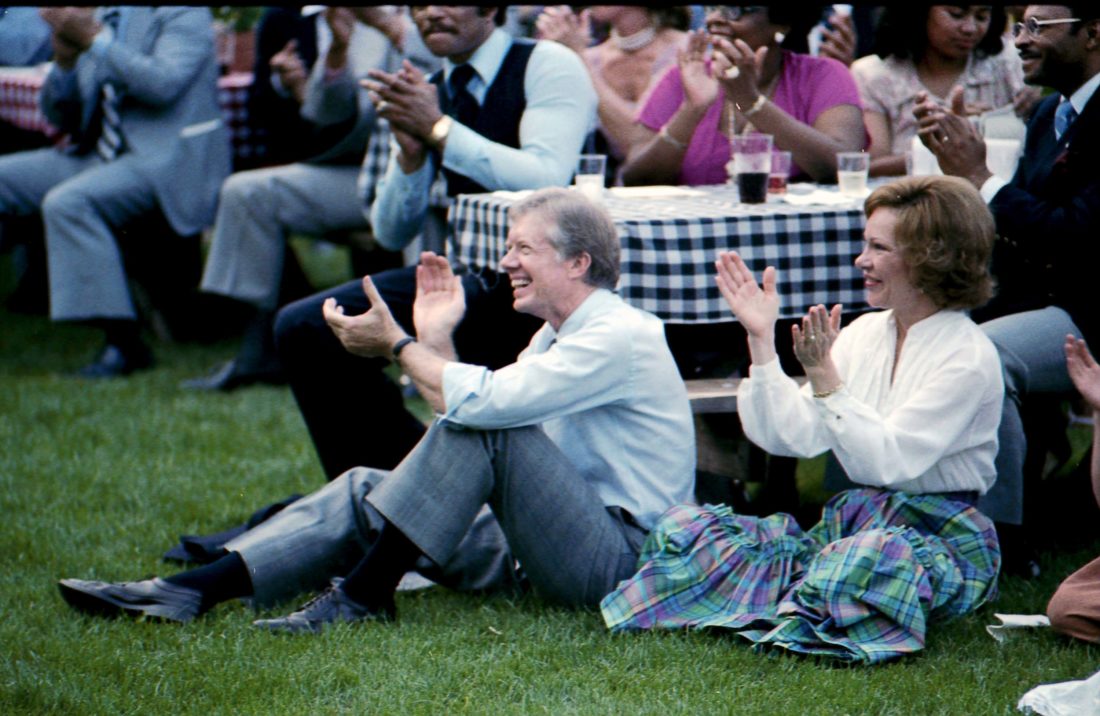

Another treat is the footage from the concerts Carter held on the South Lawn of the White House, whether with Nelson, pianist Vladimir Horowitz, or jazz great Dizzy Gillespie (who hauled the president onstage to sing “Salt Peanuts”). And he always made sure to include members of the opposition on the carefully composed guest lists. “They were wonderful social events, but they were also a magnificent tool,” says James Free, a liaison to Congress under Carter.

During the course of filming, Wharton was struck by the loyalty Carter showed to his friends, even during the lowest of times. Not long after Allman had testified in a cocaine trial, he and his then-wife, Cher, were guests at the inaugural ball at the White House. “For most public servants, that’s political suicide,” Wharton says. “But Gregg was his friend and he wanted to support him.” If there is a thread running through the film that transcends music, it is showing Carter as a man of principles with a strong moral compass that guided his time in office. One of the film’s most resonant moments takes place at the start of his inauguration speech, when Carter turns to President Ford and thanks him for what he did to “heal our land.” It was never the filmmakers’ intention to make comparisons to the present day, but rather to shine a light on a lesser-known side of Carter and the role of music during a time of change.

After editing the film, Farrell and Wharton traveled to Plains to show Carter and his family—including his wife, Rosalynn, son Chip, and daughter, Amy—the final cut, followed by a lunch of pimento cheese sandwiches and barbecue at the Buffalo Café. During the viewing at the local high school, Carter beckoned for Wharton to sit next to him. “He had a reputation for being a stickler for details, like he would correct the grammar on White House memos,” she says. “It was so nerve-racking. What if we had gotten something wrong?” Instead, he said he wouldn’t have changed a thing. “I knew based on their love of music, faith, determination, and Southern roots that Chris and Mary were right to tell this story,” Carter tells Garden & Gun.

“We always think of him as the square with the cardigan sweater,” Farrell says. “But he was very rock and roll in the sense that he didn’t care what people thought. He’s an independent thinker, and that’s why all the musicians loved him.”

Matt Hendrickson has been a contributing editor for Garden & Gun since 2008. A former staff writer at Rolling Stone, he’s also written for Fast Company and the New York Times and currently moonlights as a content producer for Ohio University’s Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Service in Athens, Ohio.

Garden & Gun has affiliate partnerships and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a product. All products are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.