Recently, while surfing that ocean of folderol we call the web, I got hung up on this particular bit of poppycock: that Al Capp, in his comic strip Li’l Abner, coined the word hogwash.

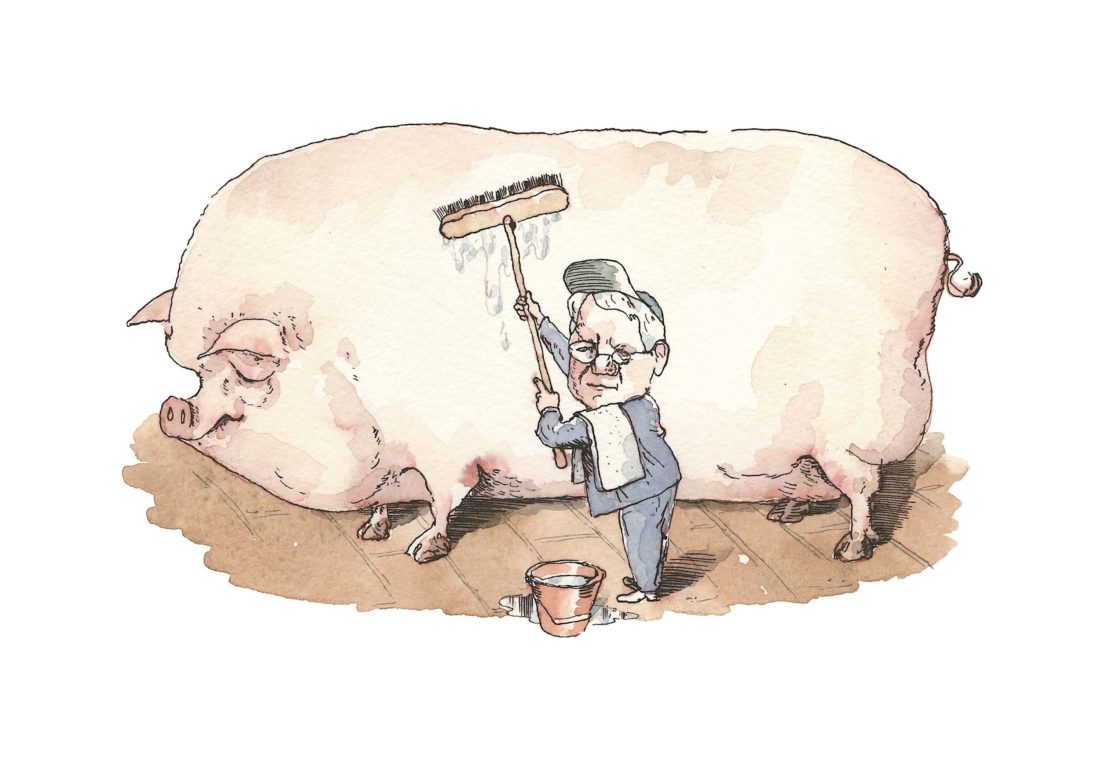

Baloney. Hogwash goes back to fifteenth-century Britain. First it meant semi-liquid pig-swill, then bad liquor, and then, a jumble of words.

That messy history has produced a fine-tuned compound. Hog for down-and-dirty, wash for euphemism. With subverbal notes of ugh and splash, of slush and gag.

Claptrap, twaddle, balderdash, bullfeathers, hooey, bosh, humbug, drivel, malarkey, hokum, piffle, flapdoodle, rot—not one of these carries the authority of hogwash.

Can we claim hogwash for the South? We know that the origin of bunkum, or bunk for short, is Southern. One day in 1820, Rep. Felix Walker of North Carolina embarked upon a long, pointless speech. Cries arose to “cut it short!” Sorry, responded Walker. He had to issue such blather for consumption in his home county: “I shall not be speaking to the House, but to Buncombe.”

Li’l Abner was set in Dogpatch, Capp’s conception of an Appalachian town. There the muddy, voluptuous Moonbeam McSwine slept with hogs. So did, on Hee Haw, the semiconsciously epigrammatic Junior Samples. (Questioned as to the inefficiency of lifting a pig to eat apples from the tree, Junior responded, “What’s time to a pig?”). But the noted British observer Fanny Trollope, in her Domestic Manners of the Americans, focused on porkers of the lower Midwest: “It seems hardly fair to quarrel with a place because its staple commodity is not pretty,” wrote Trollope, “but I am sure I should have liked Cincinnati much better if the people had not dealt so very largely in hogs.”

To which Cincinnatians of the day may well have responded, “La-di-da, Miss Fanny Trollope.” (Did she know?) But that is a matter for Ohio.

We associate the novelist Willa Cather with Western plains. But she was born in Virginia, of Southern folks. In her O Pioneers!, one character suggests to another, “Why don’t you go over there some afternoon and hog-tight her fences?”

“Ah,” I thought at first glance, “courtship in old Nebraska.” No doubt some upstanding countrywoman has resisted her neighbor’s attempts at romance, and a mutual friend is proposing he loosen the lady’s heart by, ironically, tightening her defenses—to where her hogs can’t root up from under.

But no. The lady’s hogs have been getting into our man’s wheat. Rather than gripe about it, the friend suggests, it would pay for him to improve her fences.

“I keep my hogs home,” he says. “Other peoples can do like me.”

We could extrapolate a lot of politics from that exchange. But back to the question of whether hogwash is Southern.

Mark Twain, a Missourian, was Southern at least to this extent: He was conceived in Tennessee (if you do the math), and he served, for two weeks, as a Confederate volunteer. The Oxford English Dictionary credits him with introducing hogwash, in the sense of codswallop, to America. In 1870 he wrote: “In California, that land of felicitous nomenclature, the literary name of this sort of stuff is ‘hogwash.’”

Californian, then? But hold on. In 1906 Twain wrote that hogwash had been invented (as a jocular description of Twain’s writing) by a coworker at a newspaper in Virginia City, Nevada. And in 1908, for his Autobiography, Twain identified that coworker as Howard P. Taylor, “a Southerner.” Aha!

Further research: Taylor was from Louisville. Has the case of hogwash as Southern been hog-tighted?

Hold on, again. Long after his Nevada days, Twain was reunited, to his delight, with his old buddy Taylor. The delight began to ebb as Twain brought up their adventures in Virginia City and Taylor responded with utterly un-overlapping escapades in, of all places, Keokuk, Iowa. Neither man recognized the other’s memories. “Who are you?” Twain wondered to himself. “Who am I?…It looks to me as if it is neither of us.”

Surely the old magic word would get them together: “How would you like,” Twain ventured, “to have some hog-wash now?” The reference “fell so flat that I could hear it slap the floor…I have never seen a person look blanker than he did. He didn’t look the kind of blankness that would indicate that he had forgotten about hog-wash, it was the kind of uncompromising blankness which indicated that he had never heard of hog-wash before in his life.”

Another word for a jumble of words: nostalgia.