So now I’m a diamond immortal. About time. I can tell you how immortality would be a lot better: if I’d saved my money.

Not that I ever made that much, by these kids’ standards today. My best-paid season, $152,000. That was 1981. The year I lost a $200,000 house. While still making mortgage payments on the $175,000 house I had lost six years before, thanks to the lady to whom I would go on to lose the second house. Lucky in hand-eye coordination, unlucky in love.

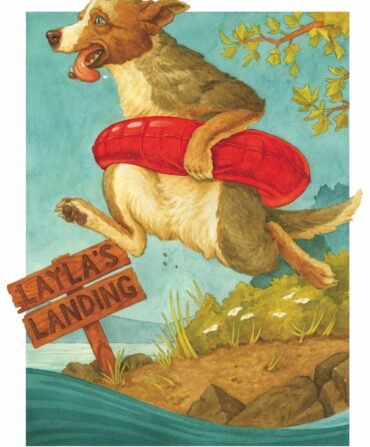

When I was nine or ten, growing up in a little Georgia town, I had only the vaguest notion of my dream. Nobody I knew had the slightest connection to that world. So I’d be in my own world, in the side yard, playing ball by myself. Throw it up and hit it, and make games up. I’d be a whole lineup. Both teams. If the ball clears the clothesline in the back, it’s a home run. I knew that much about ball.

Then one day I hear, “Hey there. Got nobody to play with?”

A neighbor, from down the road. A grown-up. Today, I guess, a kid would report him to—sorry, that’s not funny. The neighbor was okay. He just didn’t have a boy of his own. Plus, I found out later, he had played professional ball. Threw out his arm in the low minors.

So he takes me down to the Little League park and pitches to me. And I wear him out. I’m a skinny little kid—didn’t start getting any size until my teens—and he’s throwing harder and harder. And he’s chasing the ball farther and farther.

After a couple of hours, he’s sweating heavy. And looking hard at me. “Son,” he says, “you have a gift.” The way he says it, it sounds like an accusation.

I just wanted to go back to my imaginary game. But he was a coach in the Little League. He changed my legal address, or something, to make me eligible. And the rest is history. Now I’m $500,000 in debt, and a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Standing here today—I’m not going to say it isn’t cool, because it is, and anyway I don’t want you to hate me any more than you probably already do. Look at my stats! I am now the best third baseman in here, except for Mike Schmidt and maybe Eddie Mathews—especially if you look at this new number somebody came up with, Wins Above Replacement. You know this, you’re students of the game. So now I have an imaginary Replacement guy who hates me because it turns out I was 84.3 wins, lifetime, better than he would’ve been if I were dead and he had a chance to play.

Y’all like him better than me? Well, I’m just honest. If I’d been more likable—the kind of guy who tries to put himself in the shoes of people who think they’d love being in my shoes—I’d have been here thirty years ago. The baseball writers would’ve voted me in. But I kidded them too hard. So thank you, veterans committee. Couldn’t have whipped the Nazis without you.

Another of my bad jokes, no doubt. Remember the 1978 Series, when I blew the third game by getting thrown out at third? Afterward, here come the wordsmiths. I’m sitting there in my jockstrap, and I say, “Hi, guys! There’s a new one for you—a Walk-Off Caught Stealing.” None of them cracked a smile. Truth is, I beat the throw. Umpires didn’t like me either.

But I could never hold back a sharp remark. For instance, when some rickety pen pusher who never met a cliché he didn’t like, and who looked even more hungover than me, would ask me to share with him, sincerely, how it felt to hit a ball farther than he could walk straight.

Here’s how it felt, physically: natural. See the ball and hit it. Day in and day out. Till it hurts too bad and they make you quit. And you owe money.

But here’s how it felt deeper down. It felt, and it still feels, like I didn’t have what it takes. Took. I didn’t have what it took to pursue my dream.

My dream was to make stuff up. To be a writer. Ideally, of a humorous column.