I am no match for nature. If a rabbit wants to get into my vegetable plot badly enough—and he does—he is going to get into it. In broad daylight. While I watch. And he knows I’m watching, because I’m yelling at him. I chase him out and he gives me this “Oh, come on,” look. I fix the hole he exits through and he has already found, or made, or hired someone to make, another one. He knows if I were going to shoot him, I would have by now.

They tell me on the radio it’s wrong even to use a Have-a-Heart trap, because relocating an animal leaves him disoriented and vulnerable to predators. This rabbit looks pretty cosmopolitan to me, but I don’t want to lie awake at night picturing a bunny crying his little eyes out, jumping at the slightest sound, and wondering whether he will ever again see his poor old mother (who, although in her age and grief she can barely hop, must now go to my garden herself for lettuce). I put out fox urine, from the garden store, but maybe I will succeed only in attracting kinky foxes.

Why do I put up with all this? I’m a writer. I need to observe plants and animals firsthand so that I can use figures of speech involving them, without making the sort of faux pas that a guy in a bar has just made in a cartoon I keep on the refrigerator. This guy is sitting next to two animals, one of which is telling him, “No, I’m afraid I don’t know how much wood a woodchuck could chuck. We’re beavers.”

Lots of people would make that kind of mistake today. Say “grinning like a mule eating briars” and they will give you a blank look. So I was glad to have my attention drawn to a list of 106 “agrarian expressions” that originated, I am told, over dinner among Cot Campbell, president of Aiken, South Carolina’s Dogwood Stable, and friends.

“Adam’s off ox,” “ducks in a row,” “easier than shooting ducks in a barrel,” and so on. I applaud such conservational work, and would like to add three notes.

*Why is it Adam’s off ox that people say they wouldn’t know someone from? The off ox, of two yoked together, is the one on the right, further from the driver—the driver gets a lot less closely acquainted with him than with the near ox. Why doesn’t the driver position himself directly behind the team and give both oxen equal attention? If he’s plowing, he would stumble over the furrow. If he’s pulling up rocks or stumps, he’d be in the way of the rock or stump. If he’s driving an oxen-pulled cart, I guess it’s just traditional for the driver to sit to the left, at least in this country. At any rate he needs to address only one ox because the other one can’t do anything but go along. And if the driver walked to the right of the team, he’d have to reach across his body with the whip. I guess there are no left-handed ox-drivers, just as there are no left-handed-throwing shortstops.

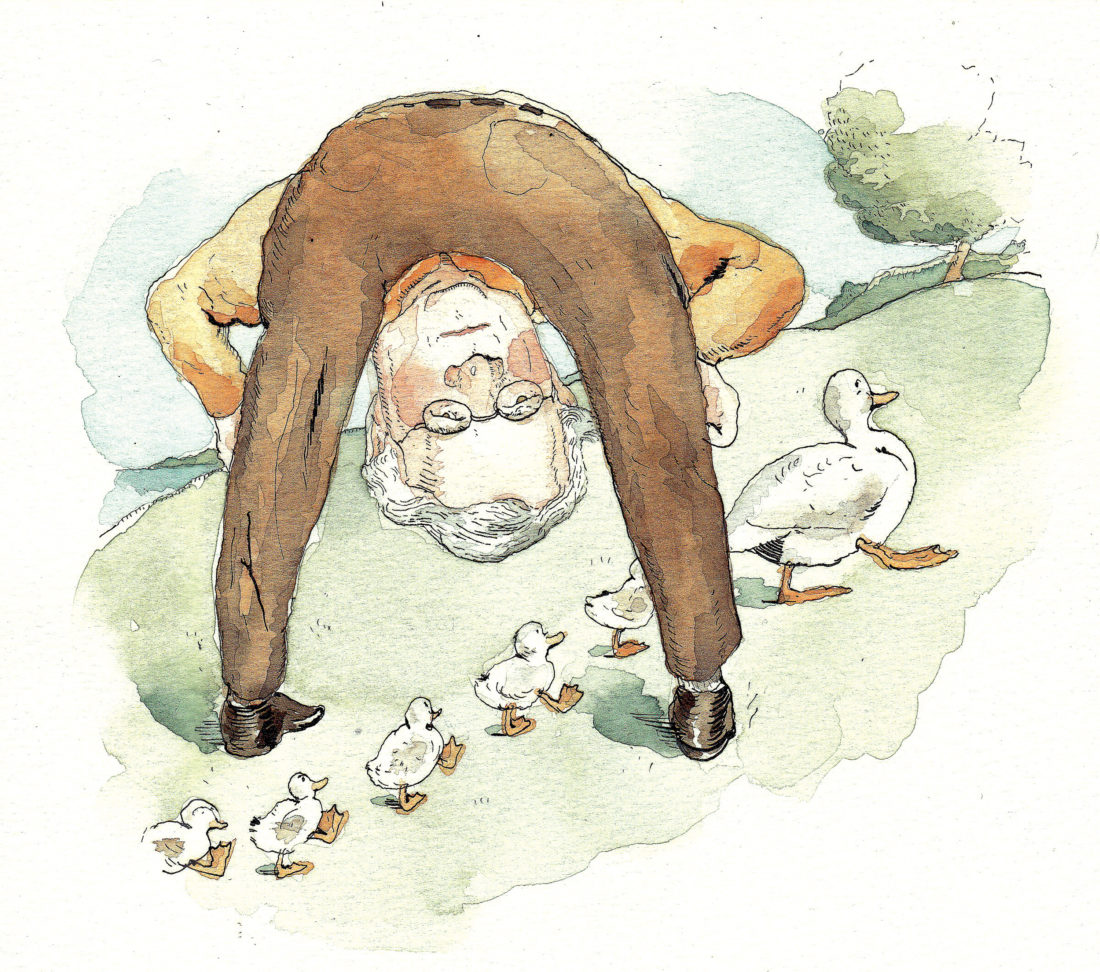

*As to “ducks in a row,” my late neighbor Jack Stanton told me that a species of duck nests in a tree until the eggs hatch. He found that out when he was mowing someone’s lawn and saw a duck drop to the ground from a crook ten feet up a big maple. The duck moved away a few feet, and then a fuzzball landed, in a heap, in the spot where the duck had landed. The fuzzball pulled itself together and joined the duck. Then another fuzzball and another, at intervals of about a minute, each one waiting until the previous one got out of the way and the mother gave a quack. When she had ten of them lined up, she led them across the road to the pond where she would teach them to find food and fly. Jack said it was the best thing he had ever watched.

*Haven’t you always heard of shooting fish in a barrel? Shooting ducks in a barrel—even just arranging the whole thing—sounds like a lot of trouble, in fact, unless they’re sedated. I for one would never consider shooting ducks in a barrel, not after hearing Jack Stanton’s story.