The lure of local ingredients caught Jimmy Sneed before most—the chef trained under Jean-Louis Palladin, who introduced Washington, D.C., to the farm-to-table ethos at his lauded Jean-Louis at the Watergate back in the eighties. So when Sneed opened his own restaurant off the Rappahannock River in Urbanna, Virginia, he made it a point to befriend the watermen down at the docks to snag the freshest hauls.

“One day, one of them brings me a bucket of these strange-looking fish,” Sneed says. “He goes, ‘Those are sugar toads: as sweet as sugar and as ugly as a toad.’ I fried a couple of them up and was blown away—the light crunch, the salt from the batter, the sweet meat nibbled off the bone. Delightful.”

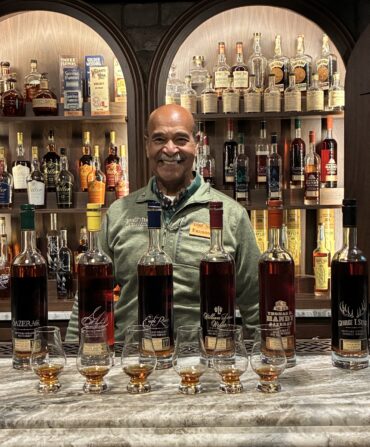

Tyler Darden

The “toads” were actually Sphoeroides maculatus, or the northern puffer fish—related to, but not to be confused with, the toxic puffers you need a trained chef to dismember. Colloquialisms abound for the boxy eight-to-ten-inch beasts: swelling toads, blow toads, sea squab. Found from Newfoundland to Florida, they enjoy a long season—roughly April to November—along the lower Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, a region with a deep culinary connection to the creatures, which, true to their name, puff up as a means of defense.

Sugar toads are caught commercially in pound nets, a fencing system placed on the bay bottom that collars just about anything swimming by. For decades, puffers were mostly dumped by the truckload onto farm fields as fertilizer, or dished up at old-school spots like the Exmore Diner, a hunk of vintage chrome on Virginia’s Eastern Shore that heralds FRESH SWELLING TOADS on its roadside sign. Now watermen such as Jason Lewis, a fifth-generation worker in the Northern Neck of Virginia, target the fish in the Chesapeake starting midsummer by baiting “peeler pots” used earlier in the season for soft-shell crabs.

Lewis and other watermen reported banner numbers of sugar toads last year, and just in time. While Sneed kept puffers on his menu when he moved to Richmond to open the Frog and the Redneck—an eatery that nabbed national buzz in the 1990s for the chef, who is now a consultant—toads only began to run riot on mid-Atlantic menus in the last handful of years. More than ten Richmond-area restaurants, some of them helmed by chefs who cooked under Sneed, have embraced the quirky fish, from a fried appetizer at the beloved Italian spot Mamma Zu to an oven-roasted version in bagna cauda at Nota Bene. They’ve been spotted in Baltimore and D.C., too, including at the James Beard Award winner Spike Gjerde’s Woodberry Kitchen and at the Dabney, where they’re served fried with hot honey, greens, and buttermilk dressing.

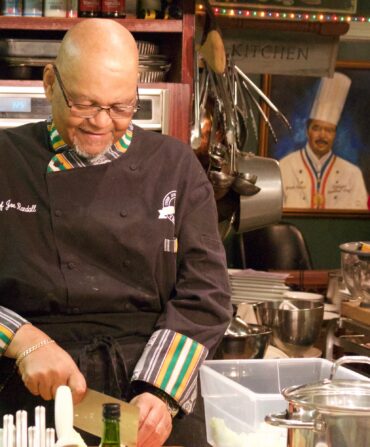

Photo: Tyler Darden

Chef Joe Sparatta, co-owner of Richmond’s Southbound.

“They’re easy to clean, but you’ll want to wear gloves or their rough skin will leave your hands raw,” says the chef Joe Sparatta, as he demonstrates their prep at his Richmond restaurant Heritage. With a couple of swift cuts, he’s able to pull the skin off in one piece. After dispatching the head and guts, he’s left with a backbone flanked with meat. Sparatta has used fillets to whip up an Asian-inspired “beef and broccoli” take on them, but a traditional tail-on fry-up—the way they’re served at the other eatery he co-owns, Southbound— still yields sugar toad sublimity.

“Jimmy Sneed really helped Richmond understand this fish,” Sparatta says. “We don’t have to do a lot to sell them.”