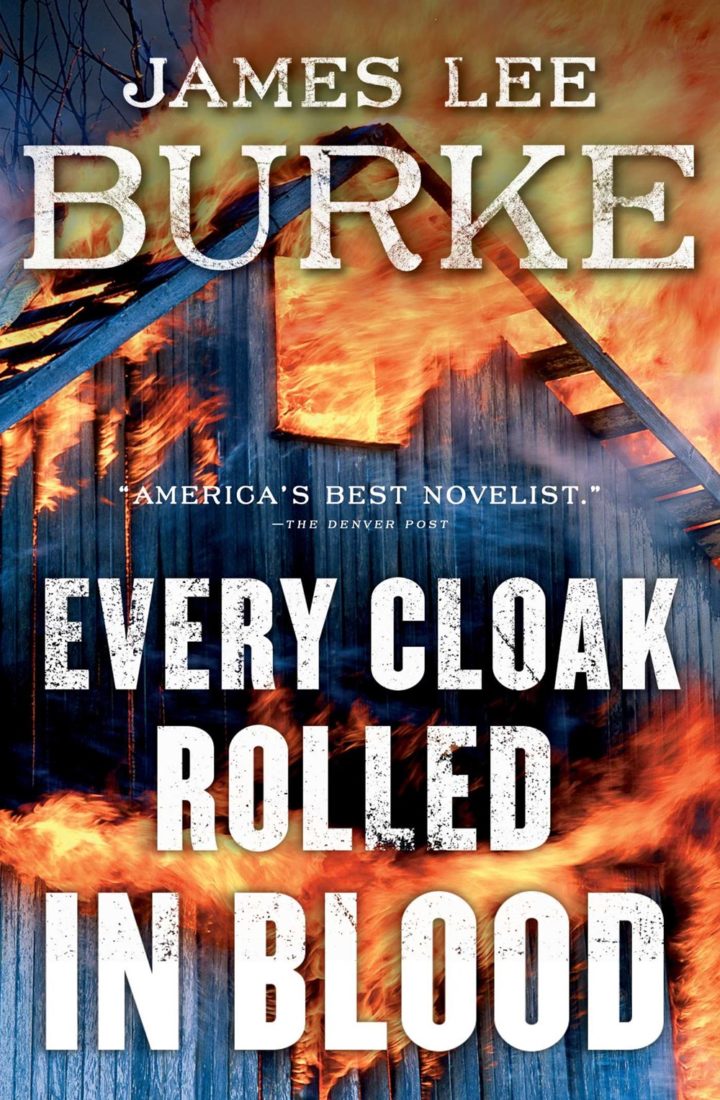

Every Cloak Rolled in Blood, the new novel from James Lee Burke, is not only a rip-through-it read, but also the most telling of the eighty-five-year-old best-selling author’s own life. The narrator, Aaron Holland Broussard, works as a novelist himself—James Lee Burke is the author of forty novels. In the work, the narrator’s daughter has recently died; Burke lost his own daughter Pamala Roberta Burke in 2020. “Pamala was one of the kindest and bravest people I ever knew,” Burke writes in the first pages of the book, which he dedicates to her memory.

Another theme is also deep, painful, real—the loneliness of aging and watching the world you thought you knew sputter away into violence and mistrust. “This novel is fiction, and the characters are fictitious, but the world and the larger human story are not fiction,” Burke writes. He adds, “It’s by far my best, even though I feel that another hand wrote it for me.” We chatted with the author about the book, his Southern roots, and how time and experience have shaped what he knows. And then he managed to slip in a dad joke.

A description in Every Cloak Rolled in Blood: “The bathroom door has a milk-glass knob on it, probably one made in the 1890s. I go inside and turn the key in the lock. The floor is made of wood…The ceiling is plated with stamped tin; the bathtub has claw feet… The simplicity of the room and its resistance to time is comforting in a way I can’t adequately explain…” The narrator then compares it to his family farm in Texas. Were you describing memories of a house you’ve known?

I was born in the Depression, and that was the way many homes were built—they reflected more of the nineteenth than the twentieth century. They were somehow comforting, the fashions left over from the Victorian era, they had a permanence to them. Homes were meant for families, and usually at least two or three generations would have lived in a house back then. People took pride in the things they did with their hands. When they built a house, unless it was just a shack, it was going to be there a long time. Many of my relatives were poor, but some of the Burke family lived in a very nice home on East Main in New Iberia, Louisiana. It’s covered by this tunnel of live oak trees with Spanish moss so dense sunlight hardly penetrates it. Some of those homes were built in the 1850s, even 1815. But there’s a dark side to the story too. The labor that built those homes was slave labor. I remember I was talking to a friend in New Iberia, a working man. We were talking about how you often see these places photographed for calendars and stuff. But there’s shadows there.

In your books, you’ve always challenged that idea that the South is happy for everyone, that there’s a complicated mythology here.

So much of the history was only good for a small sliver of people. I just finished writing another novel—I’ve been working on it for some time—a Civil War story. It deals with the war in 1862 in Shiloh and in Louisiana. That time was misrepresented in many ways, one of which is that most people there had no idea what was in the balance. One story I heard was about Fighting Joe Wheeler, a U.S. officer at the time of secession who resigned his commission and joined the Confederate army. He was heck on wheels. After the war was over, he reenlisted in the Union Army and was still in the army in 1898 for San Juan Hill with Teddy Roosevelt. He was getting a little senile. He was charging uphill; he looks over his shoulder and sees these soldiers wearing khaki shirts and blue trousers. He yelled out to the fellows around him something like, “Hurry up men, those damn blue bellies are right behind us!” [Other sources say it was, “Let’s go, boys! We’ve got the damn Yankees on the run again!”] He got his wars mixed up.

You’ve said that Every Cloak Rolled in Blood felt like it was written by a different hand than your own.

It’s the way I’ve always written. The story is always inside me. I see about two scenes ahead each day, but I never know where a story is going. I never know where it comes from. It’s just there.

Is this your most personal book?

It is, regarding the loss of our daughter. Pamala had a big following of her own. She was a remarkable person. It’s been one of those things when you discover that not all of us are having the same experiences as human beings. But in my experience, the most daunting and challenging thing is the loss of a child. Those who go through it, when they get on the other side, they’re different from that time on. This morning, I was looking at the Google newspaper and there were photographs of Uvalde and the children we lost. It’s just an agony. It’s like a nightmare that keeps going on.

The narrator in Every Cloak says, “For many people who have had a recent personal loss, superficial conversation has an effect like an emery wheel grinding the soul into grit.”

Yeah.

Do you think you use your fiction to connect with people? If you had a nonfiction book about cops, would you be getting the same reaction from your readership?

Dave Robicheaux is really the only police officer who is associated with my work in a memorable way, I think. But he’s not a police officer often, because he always gets in trouble and gets fired or throws his badge in the bayou. I published my first story when I was nineteen, and the content of my work has never changed—I’ve written a great deal about the legal system. I’ve been publishing for over sixty-five years, and in that span I’ve gotten probably thousands of letters from police officers who all say the same thing: This is the way it is.

In the middle of my career, I went without hardback publication for thirteen years. I couldn’t sell anything. I had 111 rejections. A friend of mine said, “Write a crime novel. You’ve written everything else. You only have to write two chapters to get an advance.” I started writing two chapters in long hand on a legal pad, sent it to my friend Charles Willeford who said, “This fella Dave Robicheaux may be one of the most successful police narrators in American crime writing.” I listened to him. But the only change in my writing was I gave the character a badge. I never changed how I wrote, and it was the Dave Robicheaux books that allowed me to write full time.

What job taught you the most about people?

Social work in Los Angeles. I worked in concert with parole and probation. And I had cases with people who were criminally insane, from every prison in California. I learned lots of things. I go back to my experience there, where I learned about slum lording, how poverty is a kind of industry for the wealthy. You’ll never see that story in a newspaper, but that’s the system. You learn very quickly about how to deal with the system: Don’t deal with it; don’t get your necktie in the garbage grinder.

You know if you teach a creative writing class, you always tell people to write what you know about. And of course, the more experience you have, maybe the better you write, but that said you don’t really go out and just learn it through work. It’s perception. The thing that’s hardest to write well is dialogue. To write good dialogue you have to be a good listener. That’s it. The real drama is always around us, but you’ve got to look for it. Did you ever see The Graduate? In one of the first scenes, he’s at a shopping center and he opens the door and then he can’t let go of the door because people keep going through it. They’re robotic, and he’s the only person who has any sense of perception about what’s going on around him.

Every human being is like Ulysses; there’s a universe of material there. Carl Jung believed in genetic memory, that we inherit genetically the stream of humanity. It’s all there in that 90 percent of the iceberg that we don’t see. I subscribe to that. There’s a story about Hemingway, too: Someone asked if he ever saw a psychiatrist, and he said he did every day, Dr. Smith Corona [his typewriter].

You live in Montana now. Is there anything about the South you miss?

In a lot of the South, people are hospitable and decent. We find civility. And we’ve lost civility in a lot of places. Also, Cajun food is the best food this side of the Elysian Fields. It also has enough cholesterol to clog a sewer main. But if you’re willing to give your life for your appetite, you cannot beat Louisiana food. There’s no such thing as a bad restaurant or café in Louisiana.

Everything is relative. My father told me this story. This was about 1945, he said. He was driving outside of Beaumont, Texas, and pulled into a little country store. There was an elderly man on the gallery playing checkers with a cocker spaniel, and my father said to the elderly man, “My heavens, that’s the smartest dog I have ever seen.” And the elderly man said, “I don’t think he’s so smart. I done beat him three games outta five.” [My father said,] “That’s what relative means, Jim.” Isn’t that a beaut?