The sloshing of bug juice in your belly, the sting of hot vinyl against your skin, the raucous cheers of children, and then liftoff—a legs-akimbo launch into the air from an inflatable trampoline, ending in an exhilarating splash. Any sleepaway camper from the past six decades likely knows this scene. It’s called blobbing, and it’s a cherished summer pastime so ubiquitous that it’s hard to find a camp (or all-inclusive resort or water park) in America without it. But the Blob might never have existed had it not been for some champion swimmers and a legendary Texan whose life rivals that of the fictional Forrest Gump.

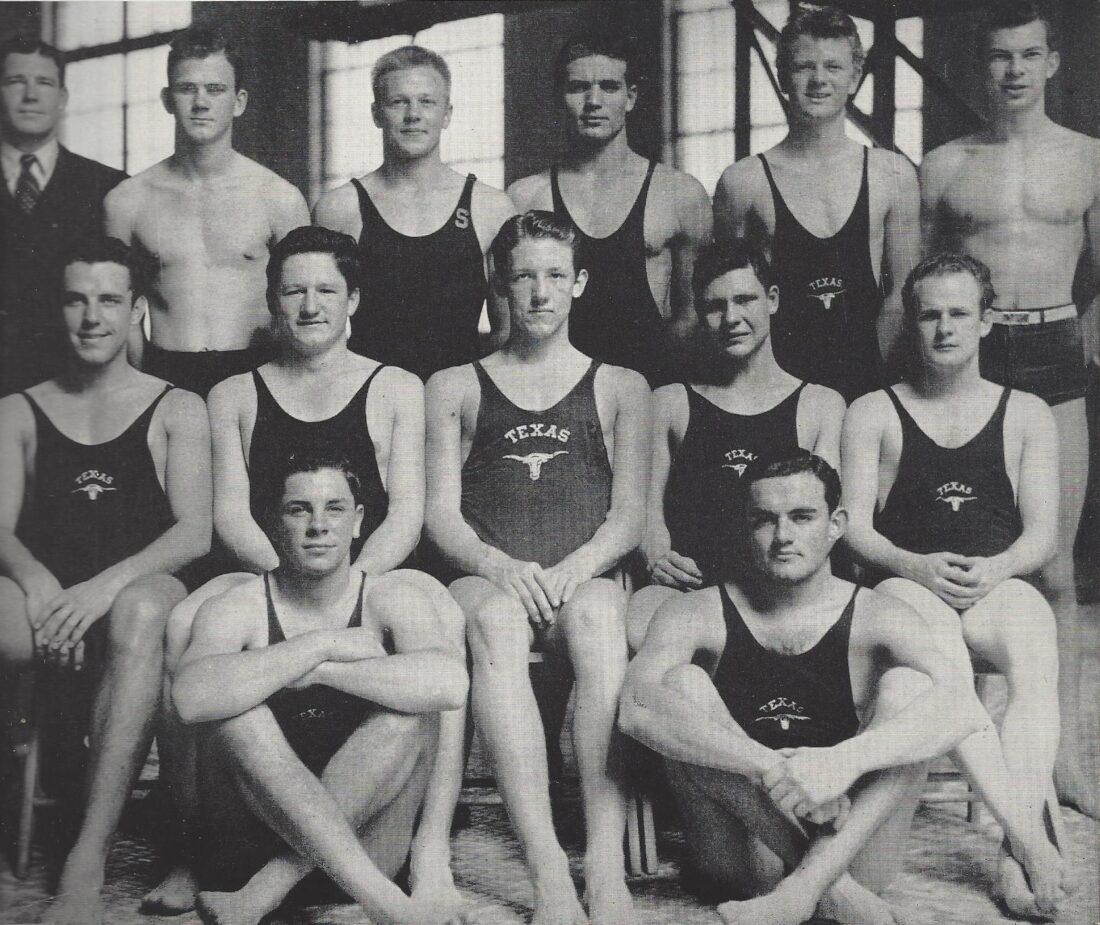

The origin story of the Blob is really the tale of Julian “Tex” Robertson (1909–2007). Called the father of Texas swimming, Tex founded the University of Texas swim team in 1935, leading the Longhorns to a Southwest Conference Championship in each of his thirteen seasons as head coach. He also founded Camp Longhorn, which would become a summertime institution among Texas children, including former president George W. Bush and the actress Hilary Duff.

Long before all that, however, Tex was just a kid in the small town of Sweetwater, Texas, who loved to swim. Of course, at the turn of the twentieth century, Texas Hill Country wasn’t where you’d expect to find a great aquatic athlete. For starters, there wasn’t much water in Sweetwater. As stories about him often begin, Tex learned to swim in a horse trough. But by the summer of 1923, he was known as the fastest swimmer in town. During the Sweetwater Rodeo that year, a cowboy named “Booger Red”—one of the most accomplished bronc riders in the country—challenged the cocky fourteen-year-old to a race: a 100-yard run and 75-yard swim with Booger on horseback and Tex on foot. Tex won.

Quite literally a big fish in a small pond, Tex set out for California at the age of fifteen with dreams of joining the Los Angeles Athletic Club swim team, known for nurturing Olympic athletes. After jumping boxcars to get there, he earned a spot on the club’s water polo team instead and, in 1932, represented the U.S. as an alternate at the Los Angeles Olympics.

It was at these Olympic trials that Matt Mann, the University of Michigan swim team coach, spotted him. Two weeks later, having once again hitchhiked north, Tex arrived in Ann Arbor.

“He didn’t have any money, so he stayed in a Michigan fraternity basement and washed dishes in exchange for free rent,” says Bill Robertson, Tex’s son. Tex didn’t mind. He had company—another athlete, a football player named Gerald Ford. The two would remain lifelong friends, and when Ford had the idea of adding a swimming pool to the White House grounds in 1975, naturally, Tex took credit.

Famous roommates aside, the plucky freestyler needed a part-time job, and he found one in nearby Chicago, which was hosting the World’s Fair and its array of carnival-like attractions. “They would put a dollar at the end of a greased pole, and kids would run across the pole and try to grab the dollar before falling into the water,” Bill says. Working as a lifeguard, Tex noticed one kid demonstrating a remarkable backstroke, so he convinced the slick swimmer to let him coach him. Under Tex’s instruction, that kid, Adolph Kiefer, would go on to win Olympic gold in 1936 and become the first man in the world to swim the 100-meter backstroke in under one minute.

Along the way, Tex honed his coaching skills. “He showed up at the University of Texas in 1935 and said ‘I’m your new swim coach,’” Bill says. “They said, ‘Okay, but we can’t pay you.’” Tex didn’t mind. He started recruiting and soon had Kiefer and other budding Olympians on his squad and winning big. With Tex’s drive and signature cheer—“Attawaytogo!”—the fledgling team ascended to fourth in the nation.

But Tex was still making peanuts, so he and his new wife, Pat, turned their attention to his second dream. Tex had spent time working as a counselor at Mann’s pioneering sports camp in Ontario, Camp Chikopi, and had fallen in love with the idea of running his own summer camp. So in 1939, the couple opened Camp Longhorn on Inks Lake. “All I ever wanted was to camp and swim,” Tex once wrote.

“They had a canoe, one camper, and sixteen UT swimmers, and they had a ball,” Bill says of that first summer. The camp grew to about forty kids and was scaling upward when an infamous event in December 1941 changed everything. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, camp was put on hold, and Tex got a call from his old friend Kiefer. The Olympian had enlisted and become chief swimming instructor for the Navy. Horrified to discover that a large percentage of sailors couldn’t swim, Kiefer called on Tex to help teach new recruits. The coach was a natural. So good, in fact, that Tex was asked to help lead a new program, the Navy Underwater Demolition Team, aka frogmen. The amphibious unit would help secure the decisive victory at Normandy and became the forerunner of the Navy’s most elite special operations force: the SEALs.

What does a frogman instructor do after war? Return to camp, of course, and bring his military connections with him.

“You have to remember, [Camp Longhorn] was built on frugality,” says Scott Johnson, the son of Tex’s then-camp director, Bill Johnson. Another UT swimmer and World War II vet (a Purple Heart recipient who lost a finger at Iwo Jima), Bill Johnson often found himself scoping out old Army surplus gear. That’s how, in 1967, he came upon a forty-foot long, 10,000-gallon rubber storage tank in a rancher’s barn. It looked like it would be the perfect water-resistant cover for Camp Longhorn’s wrestling mat, but when he got back to camp, he had another idea.

What Bill Johnson discovered he’d found was a blivet—a fuel bladder towed alongside military ships or airlifted into combat zones to store propellant.

“I remember the day vividly,” Bill Robertson recalls of the arrival of the Blob. “We pulled this green thing out of the station wagon. The camp had a massive air compressor used to jackhammer rock. Dad and some other compadres took off this big old steel plate that looked like a turkey platter on the back of this tarp-looking thing, and started filling it up.” A sort of giant pillow appeared.

“Someone said, ‘What is that? A blob?’” Scott remembers. The name stuck.

It was a halcyon age of liability-free invention, and Bill and Tex’s children stretched their imaginations to create ever more unique and dangerous ways to fling themselves onto the Blob—via trampolines, diving boards, and ladders. Eventually they settled on something called lake towers, and a novelty watersport was born.

According to Tex’s grandson, Ross Lucksinger, in his book Tex: The Father of Texas Swimming, the camp’s accountant saw the Blob’s earning potential and tried to convince the swim coach to capitalize on it. Tex said no. He wasn’t in it for the money. He wanted all camps to share in the fun. So while Camp Longhorn did get a patent for the Blob, Tex eventually gave it up. Today, Springfield Special Products makes the Water Blob, a variation of the original design they attribute to Camp Longhorn, and versions of it can be found all over the world.

Tex Robertson passed away in 2007 at the age of ninety-eight. The four Olympic athletes he helped train and the lives he saved with the frogmen are arguably his most important legacies, but to every kid who can recall the heart-pounding thrill of a launch into the sky at summer camp, his imaginative spirit might be his most enduring contribution. Attawaytogo!

Kinsey Gidick is a freelance writer based in Central Virginia. She previously served as editor in chief of Charleston City Paper in Charleston, South Carolina, and has been published in the New York Times, the Washington Post, Travel + Leisure, BBC, Atlas Obscura, and Anthony Bourdain’s Explore Parts Unknown, among others. When not writing, she spends her time traveling with her son and husband. Read her work at kinseygidick.com.