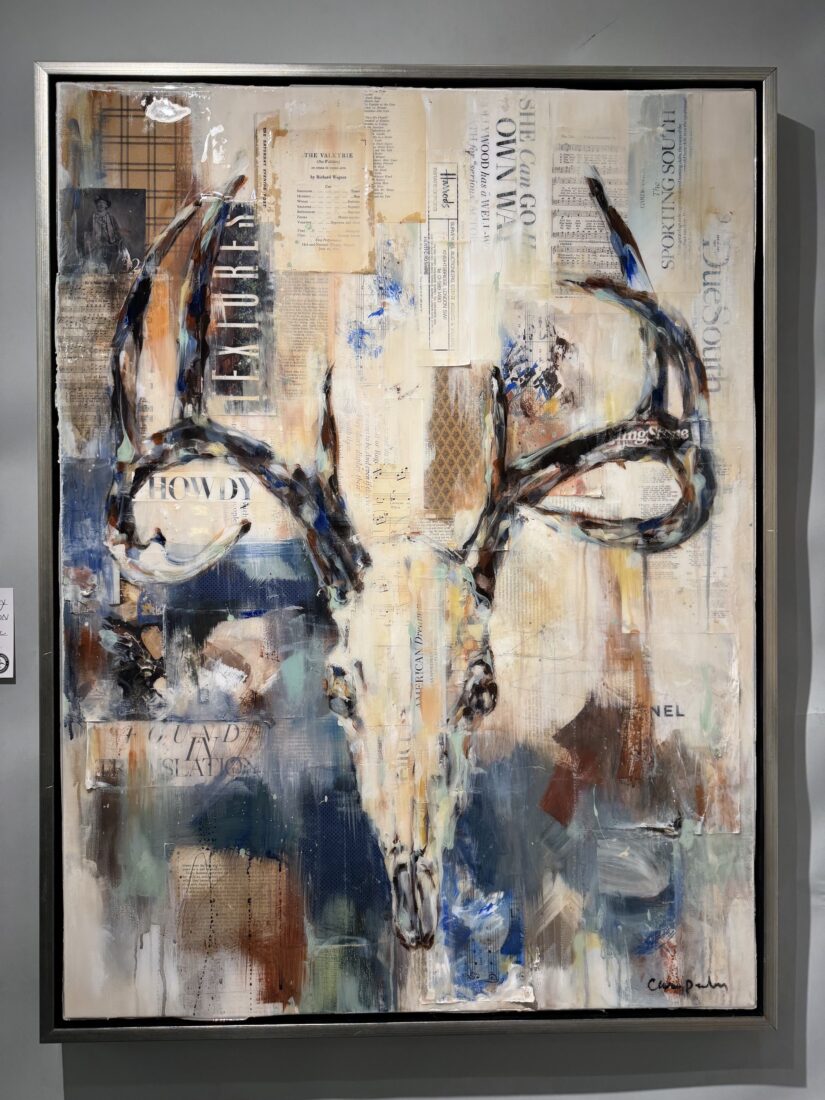

Last week I was shouldering through the crowds at the Southeastern Wildlife Exposition (SEWE) in Charleston, South Carolina, when a particular piece of art caught my eye—and rooted me in place. The work, titled Traditions as Old as Time, was a large painting of an English pointer, rigid and focused, its speckled-egg form sharply contrasting with a dark, impressionistic background. But there was plenty going on in that background. Beneath the actual dog portrait were small clippings. Two in particular jumped out to me. One was the cover banner for this very magazine. The other was a clipping with the words “Due South,” which is a Garden & Gun department I’m fortunate to contribute to from time to time.

As I took a few steps closer, more partially obscured elements surfaced. The artist, Carrie Penley, had painted the pointer on a collage of old scraps of paper, lines of type, and even sheet music. By the time I got face to face with the painting, Penley herself sidled up with her daughter, Parker, and asked me what I thought about the work.

The foot traffic pileup I caused in the aisles was probably a pretty good indication that I loved it, and I’m glad I moved out of everyone else’s way because I wound up sticking around Penley’s booth for an hour, drawn in by her expressive pieces that were unlike anything else I’d seen at SEWE. I’m a regular at the annual Charleston showcase, and every year I stumble across at least one artist whose work has escaped my attention in the past but makes a deep impression.

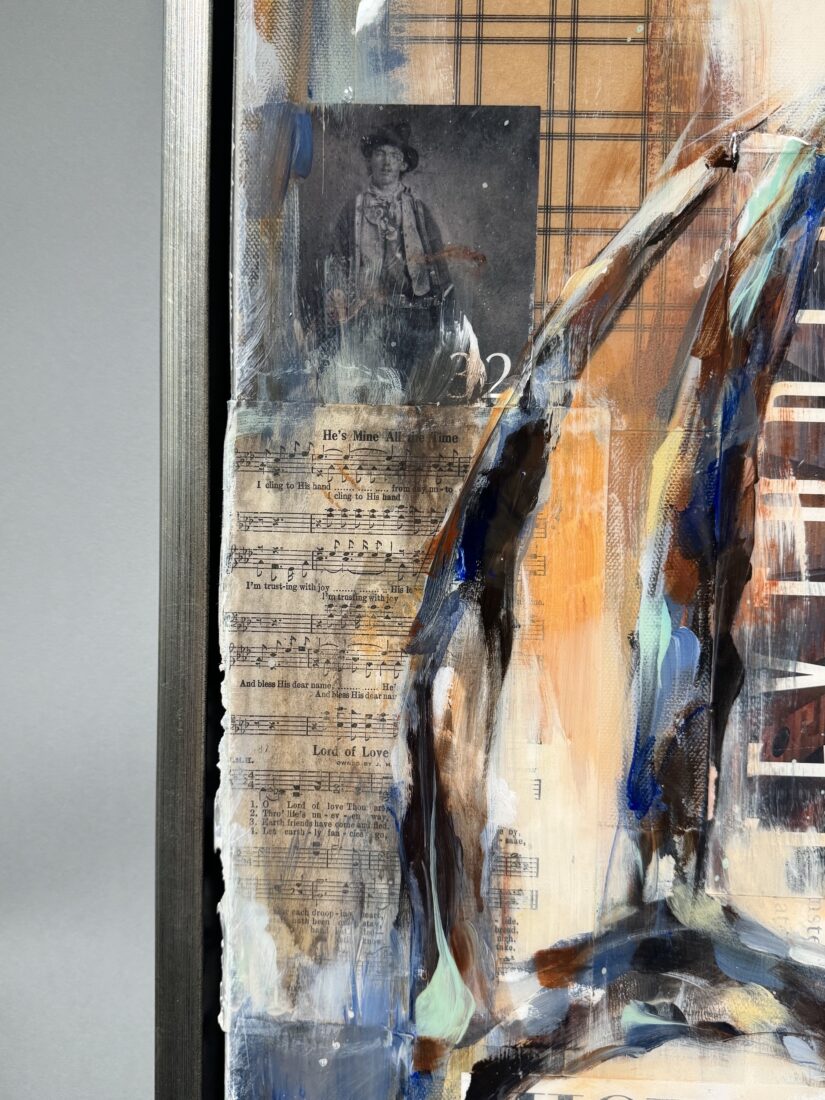

Consider her portrait of a white-tailed deer skull, titled Found in Translation. The eight-point rack seems to float above a foundation of clippings, textures, and paint strokes. There are magazine pages from Rolling Stone and a 1907 Saturday Evening Post, fabric swatches, more sheet music, an old black-and-white photograph of Billy the Kid, and even a yellowed playbill sheet from Richard Wagner’s opera The Valkyrie. The juxtaposition of such a viscerally organic thing as a deer skull and these cultural artifacts had my imagination reeling. I’d never considered it until that moment, but studying the painting, I thought about how hunting deer is like listening to music. There is the melody and cadence as I move through a deer season, bars of adagio and accelerando, crescendo and lament. Walking through the woods is also like moving through history—the tactile feeling of ancient ground underfoot, the connection to hunters of yore. I’ve long felt these things in some deep, unarticulated way, but I’d never been confronted so overtly with these seemingly disassociated connections.

A native and still resident of Carrollton, Georgia, Penley majored in advertising at the University of Georgia, where she squeezed in studio art classes to sate her love of drawing and painting. After graduation, she went to work for the well-known Atlanta interior designers Dan Carithers and Dotty Travis. Her proclivity for collage as a medium is rooted, she says, in her work for the designers, and her art is a mashup, as well, of her personal history and the subject at hand, be it bird dog, horse, or butterfly. Old gospel sheet music is a nod to her grandmother, who lived until she was ninety-four years old. She suffered from severe memory loss but could recall, Penley says fondly, every word of her favorite gospel songs. A history buff who listens to spy novels while she works, Penley rummages through vintage shops around the South and in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where Gallery Wild shows her art, keeping her eyes open for old newspapers, advertising flyers, sheet music, and photographs that help evoke themes of American fortitude: discovery, courage, trail-blazing. She’s even used old advertisements for Hermes and Chanel No. 5.

Constructing her pieces, she says, is akin to putting together a large puzzle. “There’s a push and pull between the background collage and the foreground painting,” she explains. “I want the collage, even though it’s in the background, to have weight. I’ll work on a piece at the studio, then bring it home and live with it for a while. If something doesn’t work, it’s no big deal. I just collage over it. I can get more daring with this approach.”

Daring and playful. She never points out to her buyers all of the hidden pieces in the background. Many are partially obscured with brushstrokes of paint or overlapping elements. Some buyers contact her months later, having recently discovered some hidden gem on the canvas. “I want the painting to give you a particular feeling,” she explains, “but as you experience the painting over time, you get to write your own story with it.” And not every element has to carry the emotional heft of a nineteenth-century German opera about a tragic love affair.

“I don’t want to be so damn serious all the time,” she says with a laugh. “So, with the bird dog painting, I cut out a big headline that read ‘Howdy’ and tucked it into the collage. Life can be deep and meaningful, but it’s also fun, right?”

Follow T. Edward Nickens on Instagram @enickens and find more Wild South columns here.