Teddy Roosevelt was in his first term and the Wright brothers had not finished bolting that crazy engine onto their glider in North Carolina — in other words, motorized flight didn’t exist — when my grandmother Minnie Holman was born to the planters James Bradley and Sarah Perkins Holman on their farm near Camden, in the Alabama River delta, on July 26, 1903. Minnie was raised in white pinafores and velvet hair ribbons, playing round-robins of tennis with her five older brothers on a clay court that the servants swept every morning. She ate big creamy bowls of clabber for breakfast and drank blackberry acid in the afternoons. There were no cars, electricity, or telephones. Everybody rode and shot.

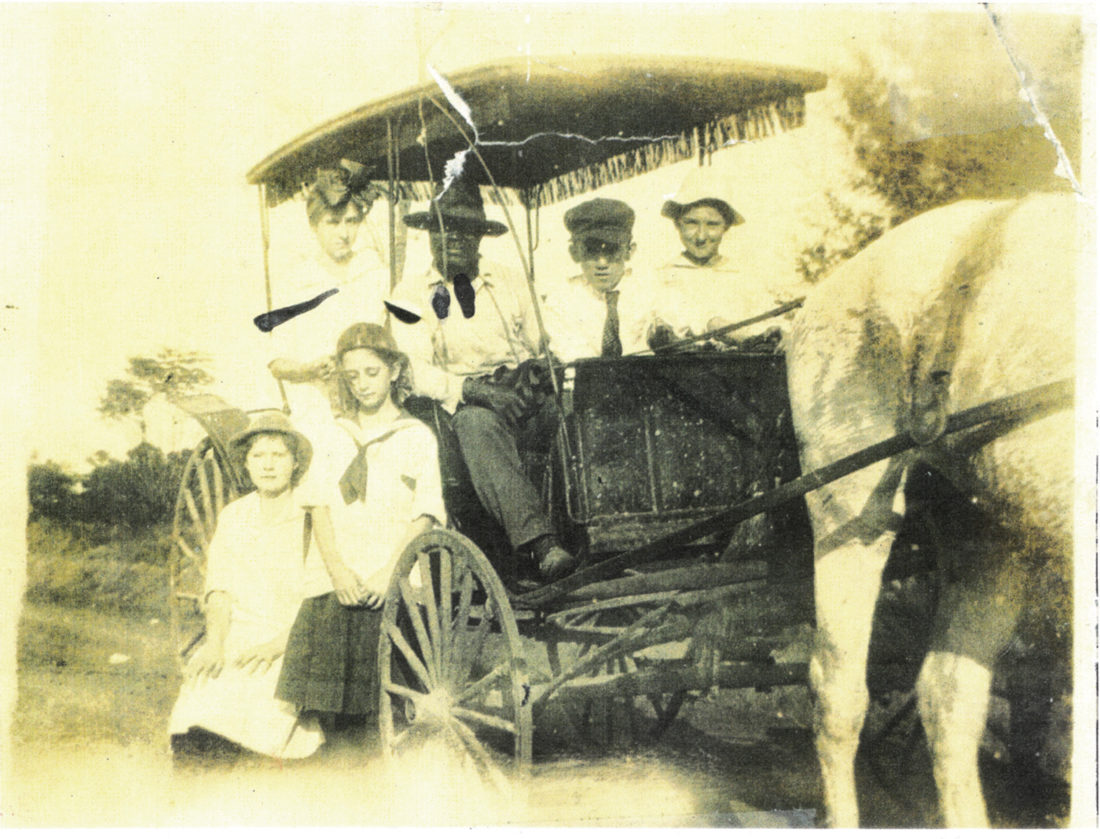

The first adults she knew were Civil War veterans, or widows such as her grandmother Fanny Tinsley Holman, or Civil War children such as her mother. When she traveled to play with her cousins, the three McLeod sisters, on their outlying farm, she was driven in a surrey with a fringed top. Although Minnie was born with the twentieth century, her childhood unfolded squarely in the nineteenth, as preserved in the amber of South Alabama.

This is not extraordinary; many Southerners are born in such eddies of lost time. What’s remarkable about Minnie, though, is that she carried the freight of the nineteenth century with such vigor so deeply into the twenty-first. Six weeks before she died at home last November, aged one hundred and four, she was grilling me on the issues of the day, asking for new books, and taking coffee up a flight of stairs to my mother every morning.

I came home to Alabama to see her last September. “How are you, Minnie?” I asked.

“Love to complain, dahlin’, but it’s not good manners,” she said brightly. “It’s boring when old people talk about their ailments. Tell me what you know — you’ve been out in the world.”

She pronounced it wuh-irld, sliding the r and putting an i in front of it, in that sugary, black-dirt way, like old bluesmen pronounce it. In Minnie’s — and Muddy Waters’ — enunciation, the word has two syllables.

We had a drink and watched the wuh-irld, then, in the form of the news from Afghanistan and Iraq. Minnie was dismayed by the wars — she had had relatives in both World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam — but she was elated by the 2008 presidential slugfest. A tenacious career woman, she’d voted in every presidential contest since suffrage was granted, except in the 1920 election of Warren Harding, for which she’d been too young. Graduating in 1924 from the University of Montevallo, formerly Alabama College, the state’s first women’s school, she went to Birmingham to teach, following her uncle and namesake aunt, both late-nineteenth-century Alabama educators. When her husband, my grandfather Joseph “Daddy Joe” Vaughn, died in 1953, Minnie enrolled in a master’s program at Vanderbilt — at fifty — and taught through the late 1960s, churning out hundreds of students.

She reveled in her retirement as she had in her work, traveling to Paris, Rome, London, New York, Japan, Norway, and her beloved Greece, puckishly referring to her jet-setting as her “little-old-lady-in-tennis-shoes” phase. In the early 1970s, she dipped behind the Iron Curtain to Yugoslavia. Marshal Tito’s intelligence service dogged her with a “tour guide” named Jidranka, whom Minnie, in vintage Southern fashion, ruthlessly killed with kindness as they toured Belgrade.

Fifteen years ago, as her ninetieth birthday rolled around, my mother, brothers, and I thought, okay, the matriarch is cresting the rise, let’s blow it out now before the down slope gets too steep for her to enjoy it. This is Alabama, after all.

We called in tents and tables, hired bartenders, bought a truckload of liquor and another truckload of the hickory-smoked pork for which Alabama is famous, invited a couple hundred people from across the South, and prayed for good weather. They all showed — relatives, friends, decades’ worth of Minnie’s students, old neighbors, new neighbors, everybody who knew and loved her, ever. Party lasted for three days. People were swilling Bloodies in the yard when the trucks came for the tents.

We coasted on this until a few months before Minnie’s one hundredth. Jesus, where did that decade go? We might be forgiven for not noticing: Late into her nineties, Minnie — captain of the 1922-1924 Montevallo basketball teams — had been sinking baskets in games of D-O-N-K-E-Y with her great-grandsons.

My mother’s idea for the hundredth was a tea dance; Minnie was in college in the 1920s, and tea dances were what people did. So, we rented out a ballroom at the old Tutwiler Hotel, bought another truckload of liquor, and invited the same crowd — minus a few faces — to dress up as flappers and swells.

Photo: Photograph courtesy of Bess McLeod Weissinger

Surrey Ride

Minnie Holman far right, in 1914 at her cousins’ farm in Coy, Alabama.

Minnie held court in one corner of the ballroom while a pianist played hits from the twenties and thirties. I found Dr. John Eagan, Minnie’s general practitioner, one of Birmingham’s most revered, and thanked him for helping her get to this day.

“Sorry, son, but I didn’t have a damn thing to do with it!” he said jauntily under his twenties-style snap-brim. “She’s just made of good stuff.”

That good stuff took her to each new day and enabled her to be herself, an outrageous anachronism, with her ancient French china and a handkerchief tucked up the sleeve of her sweater set. She was parochial, and worldly; a farm girl, and a sophisticate.

She exercised her contradictions with relish. In 2003 I was down home for another visit. She got up from her drink, went over to the secretary and pulled out a small nineteenth-century revolver.

“I’ve always wanted you to have Brad’s pistol,” she said. “Can you take it back to New York?”

Her brother Bradley, my great-uncle, had been a cavalry officer in France during World War I. His pistol was a .32 caliber service revolver with a lanyard, worn in a holster but with the lanyard around the neck so that if you fell, your pistol would stay with you.

I’d love the gun, I said, but I’d like to keep it in the secretary here in Alabama. Minnie and I had had long discussions about 9/11. The rules had changed for airplanes, I explained. The gun would get me in trouble.

“You mean you can’t take it on the plane?” she asked incredulously.

No, ma’am, I said.

“Not even,” she said, drawing herself up in her chair, “if you carried a note from your grandmother?”

The last party we had for Minnie was, of course, her wake. Off the sanctuary of First Presbyterian in downtown Birmingham, there’s a chapel named for Minnie’s aunt and uncle. In her remarks to the assembly, my mother, Sara, observed that Minnie lived so long that she, Minnie, began to introduce me and my brothers as her sons.

“Now that she’s gone, and since they are my sons, not hers, I’m here to put the record straight,” Momma said. It was the perfect joke about Minnie distorting time. People roared.

My daughter, Eliza, and my wife, Sarah, sang an old Scottish song, “Wild Mountain Thyme,” a cappella, in step-down harmony, as the Louvin Brothers would drone it. The song has a sweet line: Go, lassie, go.

And so she went.

Sometimes in Alabama in December we are lucky to get a soft April day like the Saturday of Minnie’s wake. The weather allowed a garden party hosted by her niece Ann Oliver. The sun was hot and the party flowed into the garden, as Minnie would have enjoyed it. Minnie’s cousins, the three McLeod sisters — at eighty-six, ninety, and ninety-four — showed up with a 1914 photograph of Minnie on their farm in the fringe-topped surrey.

“Your grandmother really loved that surrey,” said Bess McLeod Weissinger to me.

Minnie never gave us much chance to speak of her in the past tense. It’s what good wakes do: People practice talking about the honoree in the new circumstance, beginning with a new tense for the verbs.

Minnie made that really difficult at her wake because she had made her life span seem so normal when it was anything but. Father Time hadn’t killed her so much as she had tied him up in knots, for decades. The people a generation younger than Minnie were grandparents, or had died. Their children, Minnie’s third graders in 1959, were middle-aged. Going back beyond Minnie was also hard on the brain. Two Minnie life spans ago, Napoleon was marching on Moscow. Three Minnies ago, the United States did not exist. She threw all the clocks off.

As a result, nobody, not even Dr. Eagan, who had made a house call on Minnie the morning she died, could believe that she wasn’t at the party.

“I saw somebody sitting in her chair a minute ago,” Dr. Eagan mused. She had a customary chair at the Olivers’. “I had to stop myself from telling ’em to get up because Minnie was coming back,” he said.