Anyone who’s ever witnessed the spectacle of flying shrimp tails and flaming onion volcanoes knows the pleasures of drizzling yum yum sauce onto a mile-high pile of fried rice. Also known as white sauce or shrimp sauce, yum yum is an entirely American invention—a pinkish, mayonnaise-based condiment devised to accompany the theater and steak/chicken/shrimp line-up served in teppanyaki restaurants. Yum yum is particularly loved in the mayo-drenched South, where teppanyaki-style dining (aka hibachi, aka Japanese steakhouses) arrived in the 1970s.

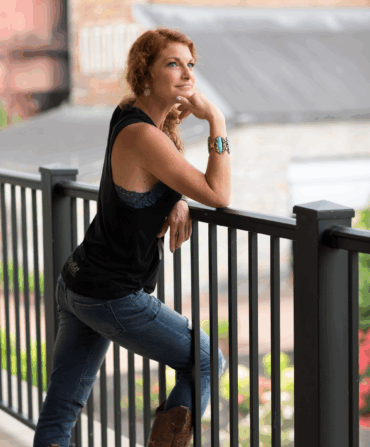

When restaurateur Terry Ho opened Hibachi Express just outside Albany, Georgia, in 2003, his customers were so primed for yum yum that they brought in containers from home so they could buy the sauce in bulk. “You’d have somebody fill a thirty-two-ounce cup, and before they got out of the restaurant, they’d be pouring it onto their food,” Ho says. “I thought, Wait a minute. Maybe we can bottle this thing.”

You’ve likely spotted the result yourself on a run to the supermarket: Terry Ho’s Yum Yum Sauce has lined grocery store shelves for a decade or so, first at regional Piggly Wiggly stores, then in Harveys Supermarkets and eventually Walmarts all over the country. In August 2021, Ho finished construction on a $12 million manufacturing plant in Tifton, Georgia, that will allow him to meet rising demand for his sauces, which now include, in addition to the original Yum Yum, a ranch version, a spicy take, a light option (now on public school menus in Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina), a Japanese-style ginger dressing, and Zum Zum Sauce, which is comparable to Zaxby’s Worcestershire-spiked Zax sauce. (Last year, with more folks eating at home, sales rose 60 percent.) “Now I control my own destiny,” he says.

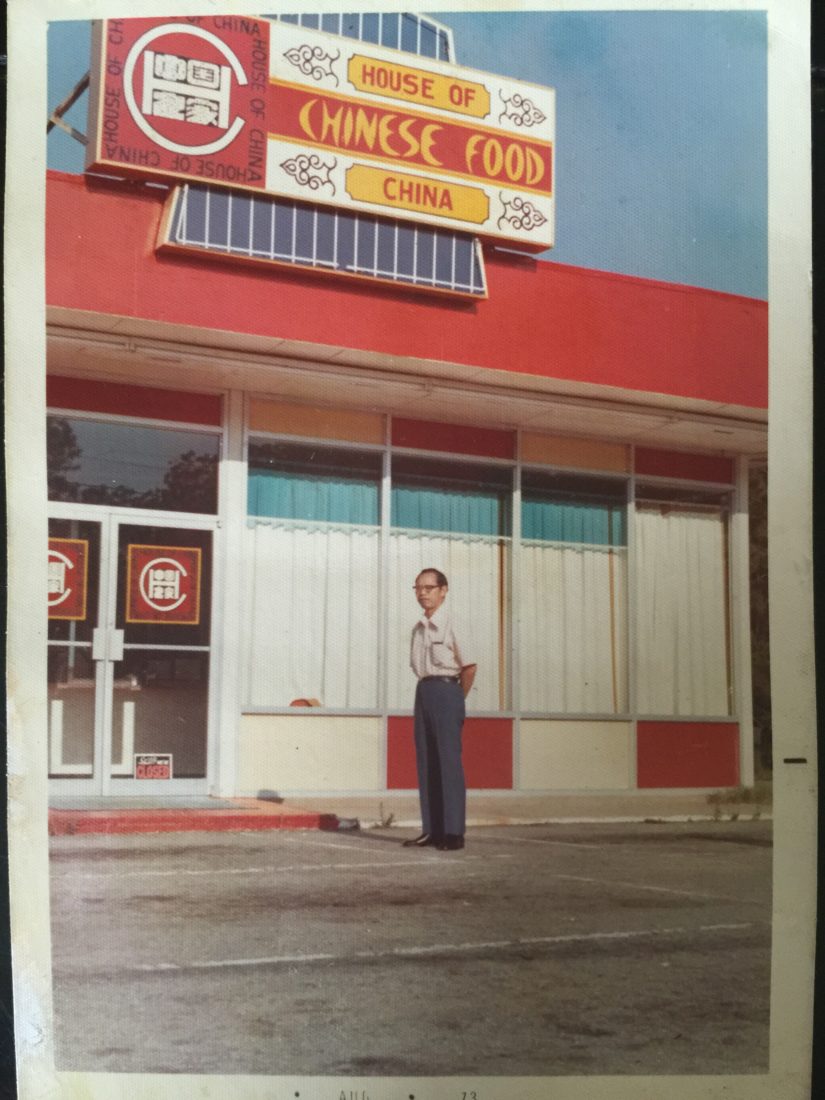

That destiny began in Taipei, Taiwan, where Ho was born in 1964. His family moved to Southwest Georgia when he was twelve. He and his older brother flew from Los Angeles to Atlanta to Albany to join their parents, who had recently purchased House of China, the town’s first Chinese restaurant. Ho sat in the plane’s window seat, and all he could see were trees and farms. “Then all of a sudden, we started descending, and I’m thinking, Where are we?” he recalls.

Three days later, Ho was working as a busboy at House of China on Slappey Boulevard, the busiest strip in town, and embarking on a new life in the American South. Now, in addition to producing yum yum sauce, Ho has his hands in restaurants in Americus, Athens, Augusta, Carrollton, Columbus, Cumming, Dallas, Gainesville, Milledgeville, Smyrna, and Valdosta, Georgia—plus a recently launched ghost kitchen, OrderEats (a low-fee delivery app used by ninety mom-and-pops in five cities)—as well as restaurants in Birmingham and Mobile, in Alabama, and Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

That evolution, though—from cosmopolitan kid to Southern restaurateur to sauce entrepreneur—was born from an intergenerational drama of war, migration, and hard work, with food as an anchor. Growing up, Ho learned the oral history of his family from elder-talk. Ken Shen Wang, his maternal grandfather, was orphaned as a child and became an apprentice to a chef in Shanghai. Wang won a cooking contest at age seventeen and was hired to prepare food on the train that ferried the revolutionary leader Chiang Kai-shek between coastal Shanghai and inland Chongqing. From that moment forward, Wang’s life would be tied up in Chiang’s political fortunes.

Chiang had helped overthrow the Qing Empire, China’s last imperial dynasty, and then unified the country. His rule began in 1928 and spanned a tumultuous period for Asia and the world. Chiang had already purged communists from the Chinese Nationalist Party (known then as Kuomintang, or KMT), and then went on to fight the Japanese in the Second Sino-Japanese War, and helped the Allied forces defeat Japan in World War II.

Wang, meanwhile, went on to open his own restaurants, as well as a barbershop and an opera house, in Shanghai, which, for a time, operated under Japanese occupation. After WWII, the KMT and Chinese Communist Party resumed a long-simmering civil war, and Wang got intel from government officials that led him to pack up and leave mainland China. “My grandfather’s claim to fame is that two years prior to the communist takeover, he booked a ship to get 147 top chefs and their families out of China to Taiwan,” Ho says.

Wang and his extended family did what they knew best. They opened restaurants, bringing their Shanghainese specialties to Taipei’s bustling Ximending district. Ho’s father, an accountant by trade, and mother, an accomplished chef, ran their own restaurants, too. But by the time Ho was a toddler, the political winds that would dislodge his family from Taiwan were already swirling.

The United States passed immigration reform in 1965 that ended preferential quotas for Western Europeans and paved the way for more skilled Chinese workers to enter the country. America was also embroiled in the Cold War and Vietnam War. Taiwan was an ally and strategic partner in both efforts, but as the possibility of Chiang’s return to power in mainland China grew more remote, the Nixon administration began to quietly explore the possibility of opening relations with the Chinese Communist Party.

In 1971, Taiwan’s political situation burst like a piping hot soup dumpling. U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger visited Beijing that year and agreed to remove two-thirds of the American troops in Taiwan. The island also lost its seat on the United Nations security council, and Nixon made his historic trip to China the next year. “The KMT felt abandoned because they relied on U.S. military forces and economic aid to maintain their power,” says Chichi Peng, a scholar of Taiwanese American immigration at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

Fearing another communist takeover, Ho’s grandfather, father, and uncle left Taiwan in 1971 for the safest place they could imagine: America. Through military connections, Ho’s family made their way to Georgia. His uncle had married the daughter of a KMT general who trained at Fort Benning. The general told the family: “Go to Columbus, Georgia. There’s a bunch of soldiers there coming in and out of Asia. They know Asian food,” Ho says.

The three men opened China Star in Columbus in 1973 and helped a friend open House of China in Albany the same year. Wang wasn’t fond of rural living, though, and moved to California. Ho’s father briefly decamped for Scottsdale, Arizona, and with a fresh Green Card, he could finally bring his young family to the States. A year later, in 1976, Ho’s parents bought House of China and settled permanently in Albany.

“The friendliness of the people here was very evident from the start,” Ho recalls. “That’s what I still love today about southwest Georgia.” Ho says he quickly warmed to collard greens and chicken and dumplings. He played linebacker and defensive tackle on his high school football team, and married his wife, Karen, a local Albany girl.

Today, the dining room at House of China is Ho’s natural habitat. He’s a born maître d’ with a natural warmth and a gift for gab. And he savors his role and lineage of culinary professionals. “My mother was a restaurant legend,” says Ho, who gradually took over and expanded his parents’ businesses. “The difference between House of China and any other Chinese restaurant is that the sauces are all my mother’s recipes,” as are the eggrolls, the wontons floating in chicken broth, the salt and pepper seafood, and the sweet-rich beef stir-fry that are all still served at House of China II, which opened in 1984.

But as for that yum yum sauce? For generations, the restaurants’ cooks came from the Ho family, but over the years, as his children took up new professions, Ho found it difficult to recruit skilled Chinese chefs to the rural South. When he first encountered fast-casual teppanyaki concepts, he saw a business that would solve his number one challenge: labor. “The average Chinese menu has 130 items,” he says. “Hibachi is a lot simpler.”

Anyone trained on a Waffle House flat-top can learn to crank out teppanyaki’s greatest hits, first popularized in post-WWII Japan. (Although the terms hibachi and teppanyaki are used interchangeably in the States, hibachi technically refers to a small open-grate grill, and teppanyaki to cooking over a large metal plate.) And although several restaurants lay claim to inventing the accompanying yum yum sauce, no one knows exactly when it came into the picture. The sauce’s popularity, though, has helped give rise to express teppanyaki restaurants like Ho’s. And the popularity of Ho’s particular spin on the sauce—crucially, he says, thinned with filtered water rather than oil, making it somewhat healthier—has given rise to a Southern empire that he hopes will keep his family tethered to food, even if future generations don’t work in restaurants.

Ho has never been back to Taiwan or visited Shanghai. “No time,” he says. So these days, his sauces have out traveled him: They’re now sold in Europe and even Saudi Arabia. “I was coming home from Columbus through Fort Benning,” Ho says. “I had just left the restaurant and finished talking to a bunch of soldiers, and they were telling me how much they love yum yum sauce. I remembered they have supermarkets on base. And the person in charge of that store? He dined at Hibachi [Express] all the time.” It only took a few phone calls before all stateside military commissaries started stocking his sauces, and the next year, Terry Ho’s Yum Yum Sauce became available at every U.S. military commissary on the planet—like a message in a bottle from South Georgia telling the story of family, food, and adapting to life, wherever it takes you.