Patrick Doughtery isn’t concerned with making his art last forever. In fact, the lifespan of his imaginative stick installations is surprisingly short—especially in the South, where humidity wears them down after two or three years. But for the North Carolina artist, who just finished his final piece in West Palm Beach this December, there’s beauty in the ephemeral. The legacy of his forty-year-long career lies in the memories of those who have seen, walked, hid, and played among his gigantic designs.

“My favorite thing is when we’re working somewhere, and someone comes up to say they’ve seen the sculptures,” he says. “Someone’s phone might have fifteen years of photographs, and they tear through their past picture life to find one photo of them or their dog with a sculpture that’s been down for ten years. They remember the day they were there, the feelings they had.”

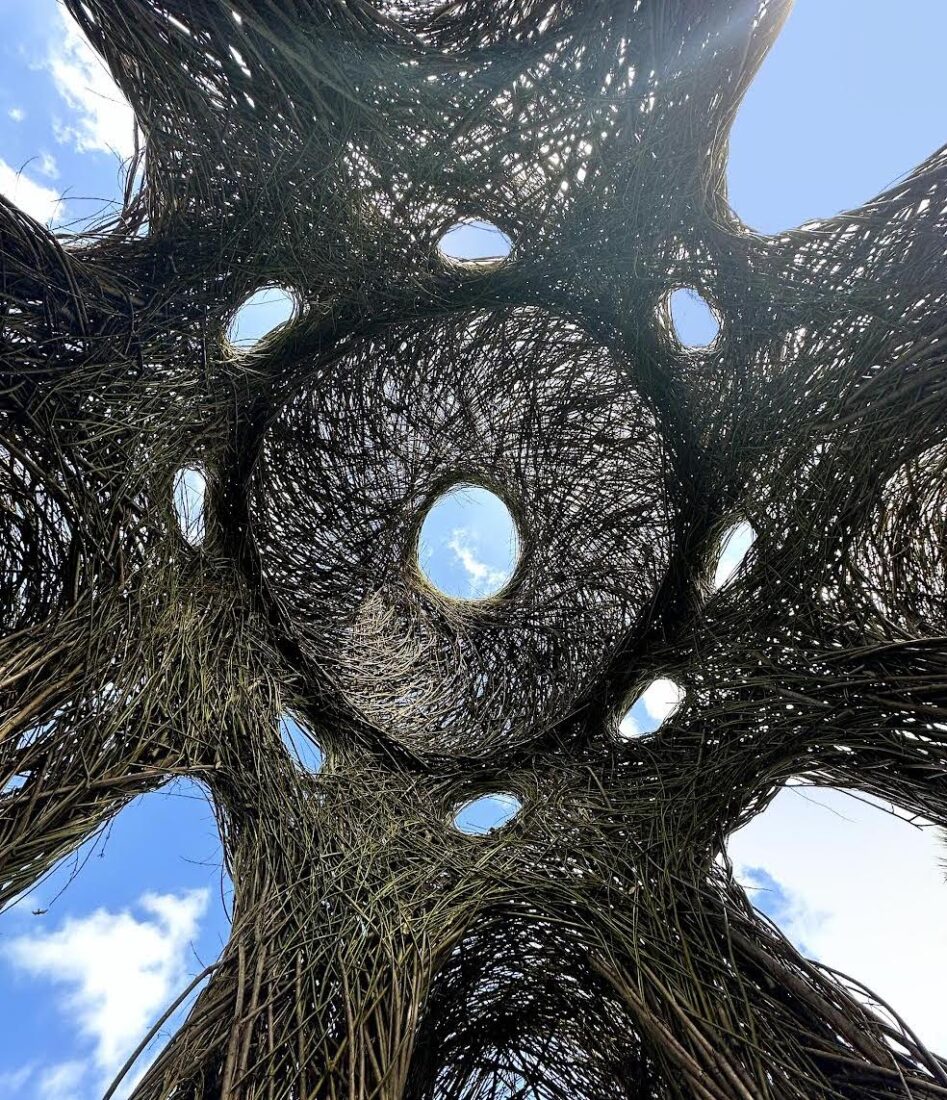

Since he started building stick works in the seventies, Dougherty has formed over three hundred sculptures across the globe, bending and shaping limber saplings into fantastic shapes. Imaginative castles, pointed towers, twisting walls, and airy domes sprawl across public spaces, allowing visitors to step inside or poke their heads through window-like openings. And although the whimsical structures look like they’ve floated seamlessly off pages from Dr. Seuss, they’re anything but effortless.

A single project demands three straight weeks, rain or shine, of labor-intensive, on-site work with a team of volunteers led by Dougherty. His son Sam joined as a full-time assistant about six years ago, taking on the role of climbing up scaffolding to help complete sculptures’ upper sections and towers. “He was part of my retirement plan,” Dougherty says. And although he’s perfectly healthy, the seventy-seven-year-old wasn’t certain he’d be able to fulfill future commissions, which he generally accepted two years in advance. “I didn’t know if I’d be there to do the same kind of work. As time goes on, you have to stop eventually.”

G&G asked Patrick and Sam more about their favorite works in the South, the memories they’ve created with their legions of volunteers, and where they’re headed next.

What’s next for the both of you?

Patrick: I’m helping Sam get his pottery kiln together. I’ve always had projects in my own studio, very low-level, pleasurable things. I’m doing a lot of work with rocks, like big rock walls. We don’t know yet if we’ll do a photo show of the [stick] work. But my wife is glad to see me home after traveling for the thirty years we’ve been married. It’s like a big reunion.

Sam: During the next year, I’m setting up a pottery business in Stokes County, North Carolina. I practiced in college, near Asheville, and I took some classes and really liked it. I think sticks and clay are similar materials—they’re both really reactive and soft. If you’re a woodworker or metalworker, everything is hard. You have to measure a lot and be real precise because you’re joining things in permanently. With clay and sticks, you react as you go. In clay, you push and pull on it. You can carve it easily. You have an idea—you don’t have to draw it out.

Your stick sculptures are a group effort. How many volunteers have you worked with over your career?

Patrick: We meet a lot of characters and we’ve had thousands of volunteers—there are a lot of closeted stick gatherers out there! We send Christmas cards to people who have sponsored the work or people we’ve worked with. We don’t have any fences where we’re working, so people are invited to come and speak to us. That has constituted tens of thousands of people we can talk to in the last forty years. It’s been so nice—at a gallery show, people only see the work during the opening. Since we’re in such public places, people have had access to look at the work, seek out our other works. They write to us and ask where they can see more.

Why exactly do the sculptures have a short lifespan in the South?

Sam: In the South, it’s humid and rains all the time. At my house [in North Carolina] right now, it’s a horrible mud hole. But in Montana, nothing can rot when it’s frozen, cold, and dry.

Patrick: In the South, the sculptures get two good years. But temporary is an okay thing. You’d think people want it to be permanent, but it holds public interest for only a few years. Like a good flower bed, you take it out and put new ones in.

Any other observations about working in the South?

Patrick: Oftentimes, there’s a general kindness in the South. The people that walk up to us have a more polite way of dealing with things. Southerners are more story-based—they stop and talk about their family, the things they’ve done, their adventures.

Last year, we worked at the Patterson School in Lenoir, North Carolina. Farmers would pull their pickups into the yard [where we were working] and talk through their window. “Generally, even though I don’t like art, I like this,” someone told us. We’re trying to make things that are appealing to the general public and people’s inner life.

What’s one of your favorite projects in the South?

Patrick: We have one in Cary, North Carolina, we really like [Fly Away Home].

What was it like working on your final sculpture, Fit for a King, in West Palm Beach?

Patrick: We had worked down at Mounts Botanic Garden before, and in 2019 they asked the minute we got there if we would come back. It was a nice bookend.

When you work for somebody a second time, you have to do twice as good, and the expectations are twice as high. They brought us Cuban food and treated us so well. We made a geometric piece before, with intertwined squares. [In 2022] we decided to make something bigger, with more height to see more places in the garden. A grand-looking place—a temple, castle, edifice—with big windows in the interior, lots of ways to look out into the garden. I imagined visitors could go over and walk through it with a grand feeling.

How did you plan and imagine so many different designs?

Sam: Patrick has a real minimal drawing [of a sculpture]. People ask for a copy and then you give it to them, and it’s like a kid giving you a painting they made—you have to pretend it’s great. There’s an idea there of what we want to make, but there’s no model or really involved drawing. We’re so used to making things.

Patrick: We have to have a sculpture idea that’s loose enough to imagine into it. As we chew it up, that’s where the beauty and character of the work come in. It’s more dynamic, working toward a feeling and idea.

Read G&G’s 2017 feature about Patrick Doughert