When I moved into a new-construction house in Charleston, South Carolina, flanked by little patches of mulch and trimmed lawn on both sides, I longed for the sense of place in the old Southern gardens I write about for G&G. The grass is always greener, right? Well, I didn’t want grass. I wanted a romantic garden full of ferny, mossy textures, tons of patina, and gracious character. So, I started braking for old bricks. I studied every trash pile on the curb and even jumped in a construction site Dumpster. A time or two or six.

With the help of my neighborhood friend JoJo, I laid a small patio area with my mismatched brick collection and lined it with thrifted terra-cotta pots. I stuffed them with whatever was on sale at the “I’m about to die” rack at Lowe’s.

My garden took a few leaps ahead when I met (and recently married!) Max, a florist by trade and total green thumb. He’s all about native plants, layers of texture, and, unlike me, patience. Max taught me that the best way to make a garden look older is to take care of the plants themselves so that we can enjoy them for years to come. Now we shuffle plants inside when it gets cold. We prune. Max tore down my temporary plastic garden shed and built one out of cedar. I open the door just to smell it. He’s also a big advocate of the garden coffee walk—a regular time to take stock of what might need help, and to simply enjoy our work, no matter what state it’s in.

Inspired by Max’s fortitude—but still wanting a couple quicker fixes—I asked a few of my favorite sources around the South: What’s the best way to make a new garden look older? Here’s what they said.

Let the roses meander and climb.

“There’s nothing better than seeing a rose going wild,” says the interior designer and tastemaker Charlotte Moss. She orders antique roses from all over, and says she particularly loves the climbing varieties Mme. Alice Garnier, New Dawn, Cecile Brunner, and Constance Spry. Another abundant bloomer with an incredible Southern story, the Peggy Martin rose is also a favorite in new and old gardens across the country. I planted it when I moved into my home, and in just two years, it has already taken over an entire exterior stair rail.

Research if there is a bit of history there.

Seek out any plant that will make your garden feel like a part of a timeline. Frances Mayes, author of Under the Tuscan Sun, wrote in her lovely most recent book, A Place in the World, about her onetime home in North Carolina and its rose history. She found local gardening club brochures and materials that shared more about the former homeowner’s rose collection and then tended the garden in homage. Do a little sleuthing—ask a neighbor or read about your area—and see what kind of botanical history winds through your place. I learned that around my block of Charleston once grew a strawberry farm, and every spring now, we tend a couple of strawberry plants.

Go perennial.

“Every year I fill in my beds with potted perennials that give the illusion of having been there for years,” says the tastemaker Keith Meacham, who sells garden goods through the shop she cofounded with the late Julia Reed, Reed & Smythe. “They come back the next year, perhaps smaller than when transferred from their nursery pots, but still reliably perennial.”

Plant in unglazed terra-cotta pots.

“Try to find old clay pots that look like they’ve been aged,” Moss says. Over time, terra-cotta pots weather beautifully in a way that a glazed pot never will. Even new terra cotta pots, affordable at Lowe’s and Home Depot, look more cohesive and natural than something shiny or plastic. One great source for investment-worthy terra-cotta pots, made in Italy, is Seibert & Rice. In the States, the legendary living potter Guy Wolff wheel-turns pots inspired by estates in England and the South. In tiny Gillsville, Georgia, the Hewell family has been making big garden pots with Georgia clay for almost two centuries. Hewell’s Pottery is worth the drive—call before you go—for Southern-made garden pots.

Make the most of moss.

Mosses are the oldest plants on earth. You don’t have to go all-in, like this serene moss garden in North Carolina does, but touches of moss between bricks and along a walkway can instantly make a garden feel ancient and moody. “I always suggest people walk around the woods and in old neighborhoods and collect mosses growing along sidewalks in the worst possible conditions,” says the garden designer Chip Callaway. “Collect clumps for high traffic areas in your garden path.” The North Carolina company Mountain Moss Enterprises also grows and ships native mosses around the country.

Build with old bricks.

For an epic greenhouse and garden pathway in Georgia, the homeowner and landscape architect Thomas Angell of Verdant Enterprises used leftover Savannah-gray bricks from the main house. Consider using surplus materials from another project or scour Facebook Marketplace and other neighbor-to-neighbor sales to find old bricks local to your area. (I can’t officially advise Dumpster diving like I do, but I can unofficially say that people throw away some surprisingly good old stuff.)

Make new surfaces look older…with buttermilk?!

This is not a Southern magazine spoofing itself…this is bona fide advice: Paint buttermilk across bricks, stones, and terra-cotta pots to encourage a natural patina. “Buttermilk on masonry promotes moss growth,” Angell says.

“Bury pots in the dirt and slather them in yogurt or buttermilk—that’s what we all did back in the day to age our pots,” says Moss in agreement. “Mist them down, slather yogurt on them, and go to bed. Even overnight, they’ll look older!”

Become a bit of a mad scientist.

The landscape architect Mary Palmer Dargan takes the buttermilk thing even further: “To soften the appearance of new masonry,” she says, “I put a slurry on that consists of yeast, yogurt or kefir, dark corn syrup, some spores from moss nearby, water, and olive oil. Rub it on whatever item, like a bird bath or statue, and then wrap it up in rags. Keep it moist. Put a black plastic bag on top, duct tape it in place, and in about four weeks you will see a marked improvement.”

Callaway has a couple of other techniques for aging masonry: “I use acrylic paint watered down and applied with a sponge, which works wonders to age new terra-cotta,” he says. “I also love to use a thin application I make out of the puffy outer coating of black walnut shells I soak in water for a few months to make a stain which can quickly age new mortar.”

Grow plants with meaning.

“Planting varieties you remember from childhood and taking cuttings from other people’s gardens link their gardens to yours and provide continuity through generations,” writes the artist Virginia Johnson in her lushly illustrated and charming guidebook Creating a Garden Retreat. A plant cutting could come from a neighborhood plant swap or a friend’s garden (with their permission of course). Herbs are some common varieties to grow from cuttings, but even showy floral stunners like camellias can be propagated through a process called air layering, described here by the Middleton Place camellia steward Sidney Frazier.

“You may remember lilacs from your grandma’s yard by their fragrance and size,” says Kristen Pullen, a manager at Star Roses and Plants. She suggests planting flowers you have a connection to—you’ll be happier to tend them and keep them going for longer. And for those lilacs, her pick is New Age Lavender Syringa, a compact, mildew-resistant variety that will mature faster than traditional varieties. Scents included.

Plant in the cracks.

“If you have a courtyard garden and it’s part flagstone, plant things in the cracks of the stones that look like they’re spilling over the edges,” Moss says. “A creeping thyme or button fern or Irish moss.” A plant that sprawls and tumbles gives the impression of age and character. “It makes it look like the stones have really been there a while if they are partially covered up.”

Group bulbs.

The plantsman Jenks Farmer has for decades driven back roads and hunted in cemeteries and ditches and abandoned dance hall lots to find his incredible collection of rare plants, namely the crinum lilies he’s staked his reputation on. “I look at how bulbs grow in old gardens—they’re always in clumps like little ponytails,” he says. “So, when you plant your bulbs in a new garden, or any garden for that matter, plant in groups of eight to ten. Use a post hole digger to make a perfect circle and plant the bulbs side by side.”

Pick a main color.

“If you look at established gardens, you see that there is often a flower color that’s gone wild throughout,” Farmer says. Repeated colors bring harmony and draw the eye along. “You can achieve this look easily with biennials and annuals. Cool season plants that you would seed in the fall include nigella and larkspur. In warmer seasons, cosmos are reliable.”

Create a base of evergreens.

Something that will always be green year-round gives a garden structure or “good bones.” “Evergreen trees are great in this regard,” Dargan says. “I go for large plants with character, such as an odd-shaped limb with upturned appearance.”

Throw around old words for effect.

Got two lemon trees in pots? No, you have an orangery, a potted citrus garden. Those bushes over there? That’s the beginning of your parterre garden. And the shed is much more jolly as a folly. Words matter when you’re writing your garden legacy!

Keep transitions in mind.

A harsh line between concrete, grass, and edges is great for a pop of modern design, but if you want an older look, blend a bit. Let native grasses lean over a walkway; transition with stones or pebbles or pea gravel. For a truly Southern look, use oyster shell gravel, like on this Charleston patio.

Use historic paint colors.

On an outbuilding or fence, watered-down whitewash is always a classic choice. Historic colors for sheds also include dark greens. On our cedar shed, we used the happy green shade Acanthus from the Colors of Historic Charleston palette from Sherwin-Williams.

Get creative with fencing materials.

If possible, construct fences and outbuildings with reclaimed wood like the treasures unearthed by Re:Purpose Savannah and at salvage yards. A design team in Texas even built a gorgeous fence with antique tobacco-drying sticks for immediate charm around a potting shed.

Plant ferns.

Ferns date back some 360 million years, but they don’t have to give off Jurassic Park vibes. Native ferns tucked into a brick wall, grouped in a shady spot, or even hanging from a basket on the porch look cool, romantic, and timeless.

Get wild about vines.

“Quickly cover new walls to dull the sharpness of fresh masonry,” Farmer says. “Vines indicate the passage of time. And you just can’t fake it—but you can mimic it with fast-growing vines.” Farmer’s go-to option is, surprisingly, gourds. “Loofah is at the top of my list,” he says. “But cucuzza or any old gourd seeds that you shake out of a dry gourd will work.”

Fast-growing native vines do double-work as pollinator supporters, too. Kelly Funk, the president of Jackson & Perkins, prefers Major Wheeler honeysuckle, a native to the Southeast that draws hummingbirds and butterflies. “This native variety of honeysuckle brings any garden to life with tones of red and yellow,” she says. “The lush leaves remain dense and lovely until frost, and the flowers keep blooming as well, unbelievably abundant until summer’s end.”

Prune.

It might seem counterintuitive, but trimming plants makes them grow bigger and healthier. Pruning for shape also helps light and air move through plants, giving them a look and sense of longevity. (See: The timeless joy of an espaliered fruit tree).

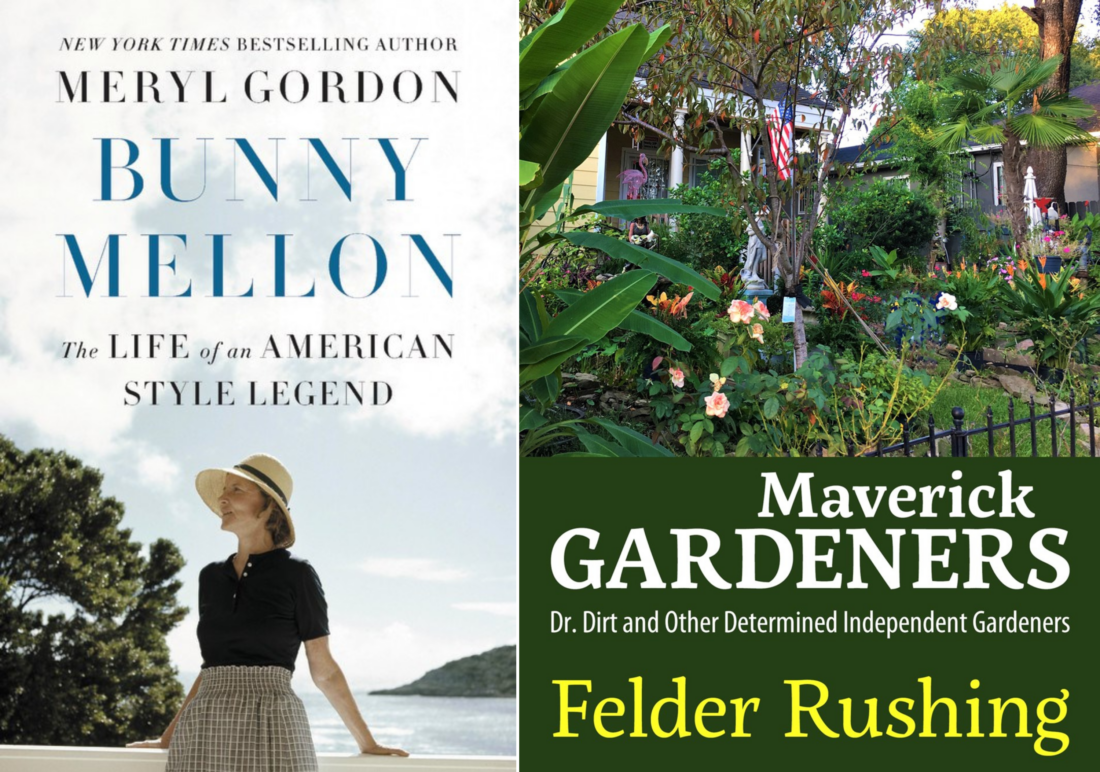

Perhaps no garden tastemaker was as powerful a prophet of pruning as the late Bunny Mellon. She redesigned the White House Rose Garden in the 1960s, and across her properties, including at her estate Oak Spring in Virginia, she was a masterful pruner of trees and little potted topiaries. In the fabulous memoir Bunny Mellon: The Life of an American Style Legend, the author Meryl Gordon writes, “At the Mellons’ properties in Virginia and Cape Cod, the gardeners who maintained the grounds frequently discovered little piles of trimmings beneath the trees and bushes. The twigs and branches had been left by Bunny, who liked to walk the land using her pruning shears in the way an artist wields a paintbrush, improvising to change shapes and the play of light.”

Accessorize just a bit.

“Plants alone do not a garden make,” says the Mississippi garden writer Felder Rushing, author of the delightful Maverick Gardeners. “All good gardens, no matter the style or size, have some sort of accessory or art that truly personalizes it. Hard features create instant style and mood and keep a scene going all year. Accessorize with an antique urn, Victorian metal bench, oversized birdbath, heirloom gate, or wooden structure that glows with a patina of color stain. One caveat: It is entirely possible to over-accessorize. All it takes is a strong hint.”

Purge plastic.

Nothing kills an old-school vibe more quickly than plastic. Get plants out of those thin plastic pots they come packaged in, whether you plop them in the ground or tuck them into terra-cotta with a natural trellis made from a stick or bamboo. “I love to plant nasturtium in my old terra-cotta pot and let it trail up a primitive trellis made by tying three bamboo garden stakes together at the top,” Meacham says. Remove any stickers with barcodes on pots, as well as those plastic label sticks. Swap them out for cool metal tags, or hold onto them to remember what varieties you planted…

…And keep records in a garden journal.

Many of the great gardeners of generations past kept meticulous garden journals, and it’s just as important today for anyone who wants to keep track of which varieties thrive and which are duds from season to season. G&G contributor Kinsey Gidick chatted with a few pros about the best way to keep notes here.

Beware of storms.

In the coastal South, hurricanes threaten life in all forms. In areas that deal with major storms and flooding—most of the world these days—consider the native plants that have withstood storms for eons. The South Florida landscape architect Raymond Jungles works with natural formations of hardwood hammocks, mangrove forests, and coastal dunes in his designs. In one, the Coccoloba Garden, a seven-acre spread in Islamorada, Florida, featured in the book Beyond the Garden: Designing Home Landscapes with Natural Systems, Jungles took note from Everglades ecosystems when he created terraces and pools for drainage, saved tall Bailey palms and native grasses, and planted dune-loving spartina, silver saw palmetto, and spider lilies that can withstand storms and even thrive when nearby non-native plantings get totally uprooted and gardeners have to start again.

Don’t kill it!

Plants and trees, like people, age, get sick, and heal. Some of the most interesting sights in nature involve gnarled tree branches and healed-over bark spots on ancient trees that have lived to tell tales. If a plant or tree in your garden suffers cold or storm damage, research ways to nurture it back to health. The Arbor Day Foundation has a super helpful website with tips for storm damage.

Plant bigger plants…

This sounds too simple, but it’s true—plant older trees and plants when you can. To figure out which trees will thrive in your area, you can use Arbor Day’s Tree Wizard tool to identify hardiness zone, soil type, and sun exposure. Then you can specify your results by height, spread, and growth rate.

…Or maybe smaller ones.

In his forthcoming garden book, Jon Carloftis Fine Gardens, the Kentucky designer describes the intrigue of using dwarf plant varieties. A dwarf magnolia or hydrangea quickly gives dimension beneath a larger tree and is easier to maintain.

Callaway agrees: “One trick I love to do is vary the size of repeated plants,” he says. “The English call it ‘cloud’ planting. Instead of a clipped parterre with perfectly matched boxwood or holly, vary the sizes slightly to hint that they were not all planted last week. I buy three-gallon, five-gallon, and seven-gallon plants of the same varieties and artfully arrange them to make edging for flower borders. Dwarf yaupon hollies, blight resistant boxwood, and Japanese hollies are great for this.”

Take stock of your tools.

Classic tools are handheld history. The forged tools coming out of Virginia’s Blanc Creatives are heirloom-quality, and a set includes a hand rake, trowel, and weeder. The English company Haws has been making watering cans since 1886; they’re classic and time-tested. The Maryland company Garden Artisans sells these gorgeous myrtle-wood trugs (a neat old word for a garden basket) handmade by a retired shipbuilder and fastened with copper nails. Fill it with cut blooms or herbs for garden-to-countertop style.

Seek out historic gardens when you travel.

On a blustery cold trip to Amsterdam this January, Max and I found warmth—and tons of ideas—in the Hortus Botanicus greenhouses (among their many plants, they even grew Southern okra from Clemson!). Seeing how other horticulturalists have grouped plantings or laid out their designs will help with your own gardening plans. And you don’t have to take a trip to see the gardens of France, Italy, or England (but say yes if you get an invite). The South offers plenty of inspiration too, whether in the 1700s camellias at Middleton Place near Charleston, Winston-Salem’s Reynolda and its historic greenhouse, or the gilded age estate Vizcaya and its meandering tropical gardens in Miami.

Wait and see.

Of course nothing will help a garden feel older and more established than time itself. (I hear you loud and clear, Max!) As gardeners, we must spend time in our gardens every day and notice things—what plant is doing well over here, and what might need a change. Time tells all.

Take this encouraging reminder from the British gardening guru Monty Don: “There’s a huge temptation to fix a garden in one point in time and to see it as an installation. The truth is no garden is like that. They change all the time. They’re not precious things. They’re both very robust and very capable of reinventing themselves.”

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book. All books are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.