In a just world, Nancy Hale (1908–1988) would need no introduction. Her name would be soaked into the American book consciousness as thoroughly as those of her contemporaries F. Scott Fitzgerald and Thomas Wolfe. But the world isn’t just, as we all know or eventually learn, and thus chances are slim that you’ve come across mention of her name, much less ever read a sentence of hers. Hale wrote bits of everything (memoirs, plays, biography, children’s books), but the voltage ran highest and hottest in her fiction: in her eight novels, such as her 1942 best seller,

The Prodigal Women, but especially in her hundred-plus short stories, so many of which appeared in the New Yorker that for a time she was all but a columnist. Hale’s stories, like her characters, tended to be cool to the touch, but, as with Edith Wharton, roiling just beneath the surface was a red-hot molten core. At the time of her death, however, her renown had already begun to blink and fizzle; only two of her many books remained in print. After that, it was mostly lights out.

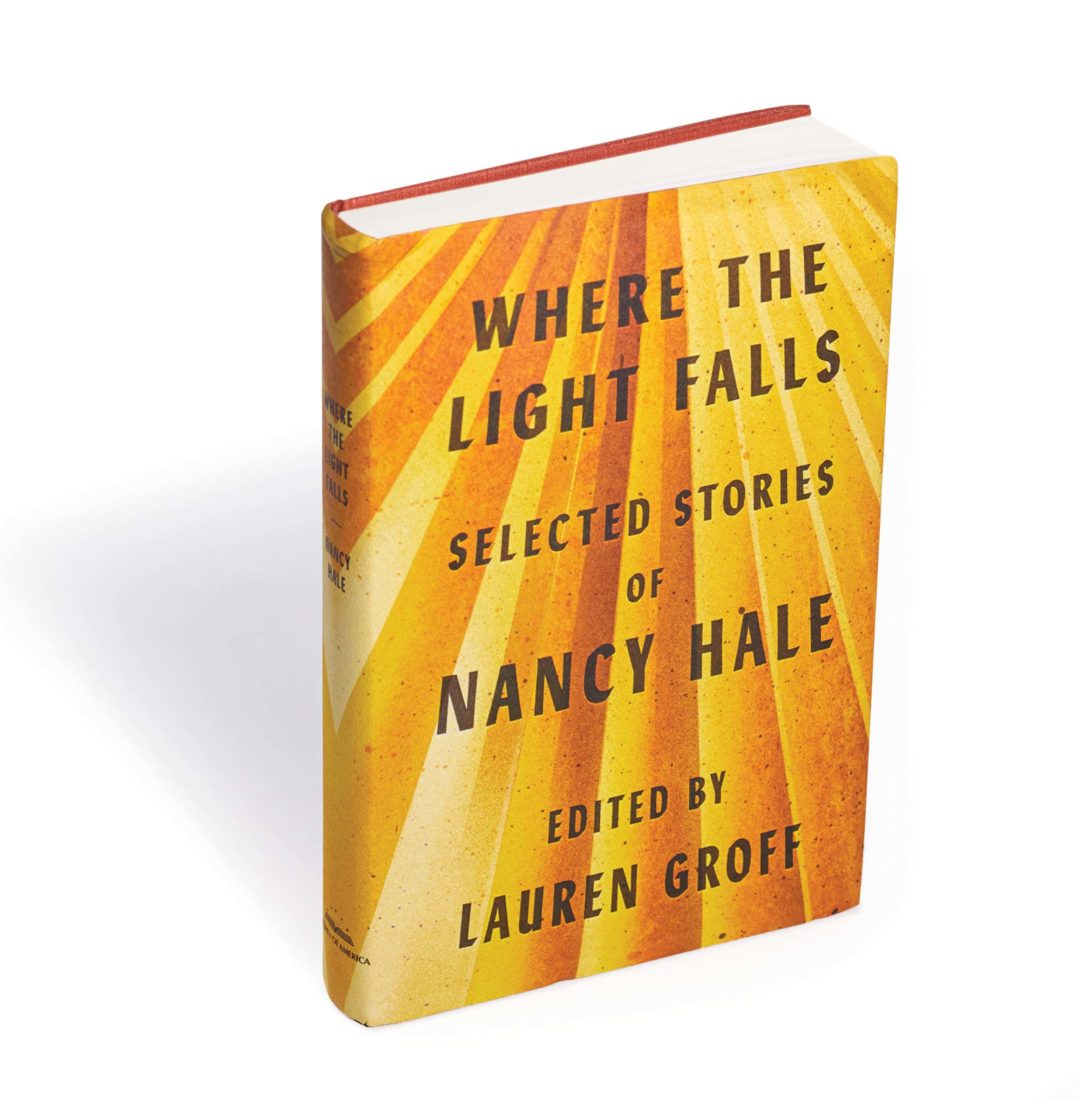

Obscurity in prose is often the realm of error, as Luc de Clapiers wrote, but obscurity in literary regard can also be a realm of error. Where the Light Falls: Selected Stories of Nancy Hale, edited by the novelist and short story writer Lauren Groff, aims to correct that error. “It makes me riotously angry that such a brilliant and important writer as Nancy Hale could fall out of public consciousness,” Groff writes in her introduction, and to make her case she’s assembled twenty-five of Hale’s stories, from the 1930s through the 1960s. Groff’s anger is fair; Hale’s decades-long disappearance from bookstores (not to mention the nebulous canon) is, at best, a monumental oversight, and, at worst, an equally monumental example of what Groff calls the “quiet, deadly, constant devaluing of women’s work.”

The stories, like Hale’s life, are chiefly set in two locales: the prim quarters of New England, including Hale’s native Boston, and the courtlier parts of Virginia, where Hale lived for almost fifty years. (New York City, where she resided as well, also makes a few cameos.) Most of the protagonists are female, from girls to grandmothers. “I specialize in women,” Hale once told an interviewer, “because they are so mysterious to me. I feel that I know men quite thoroughly, that I know how, in a given situation, a man is apt to react. But women puzzle me.” We encounter these characters in various straits of satisfaction, dissatisfaction, or more commonly an ambiguous space in between: a sixteen-year-old whose sexuality burgeons like a tornado, “incomprehensible to her and pulling her apart,” and draws into its vortex her bewildered Irish riding instructor; the acerbic, no-nonsense mother of a teenage boy who, after depositing him at his Virginia boarding school, finds herself unable to withstand a tidal surge of emotion that both is and isn’t maternal nostalgia; the femme fatale of a small Southern town who turns out to be not quite so fatale as the townsfolk believe.

Plot and character description, however, sidestep the essence of many of Hale’s stories. They’re often, like paintings, studies in emotion, and as with paintings the intensity of feeling can sometimes sneak up on you, hours or even days later. Behind the soft gloss of her prose, and the polished manners of her characters, Hale explores the spectrum of feelings, never more penetratingly than when she charts the overlap or collision of contradictory emotions: the simultaneous joy and melancholy of motherhood, for instance, or the terrible yet exquisite agonies of young love. Or in this passage, from “The Earliest Dreams” (1932), in which Hale describes a child in bed listening to “bitter and sweet and sorrowfully reckless” music wafting up from the room below: “You felt so sad, so happy and so sad, because something that was all the beauty and the tears in the world was over, because something lovely was lost and could only be remembered, and still you knew that for you the thing had not yet started.”