It’s an incredibly vulnerable thing for me to even admit, but for a long time, being a chef on TV saved me from being a chef in real life. So much so that by the time I turned forty, the restaurant that once upon a time couldn’t run without me—my flagship, Chef & the Farmer, in Kinston, North Carolina—could no longer run with me.

In the years my series A Chef ’s Life aired on PBS, Chef & the Farmer had morphed from a special-occasion restaurant into a pilgrimage destination. Guests traveled from near and far to scratch an itch more gnawing than hunger. Fans of the show wanted to see me, and when they did, whether they hailed from Raleigh or Rhode Island, they wouldn’t leave their seats till I visited their tables. My presence halted the flow of service.

I was a distraction and needed to remove myself, and my dirty little secret was I wasn’t 100 percent mad about it. At that point, I felt relieved that my life was no longer going to be a revolving door that only opened into C&F. At the same time, I also felt like a fraud. Viewers who had watched me toil, chop, laugh, and complain at the edge of my cutting board had been touched enough by those messy scenes to journey to Kinston. I imagined their giddy anticipation as they boarded planes and Google Mapped their way east. The show told them I’d be perfecting food at the kitchen pass, which I hadn’t actually done in years.

It’s not that I disliked being a chef. I relished every single creative aspect of the job. I loved the rhythm and camaraderie of the kitchen. I even appreciated the pressure of service—one so urgent it made our dining room feel more like an emergency room, even though we were only searing scallops, not suturing wounds.

What I couldn’t stomach was how running a restaurant ate up every morsel of time and energy I had. Since opening in 2007, I had traded everything, it seemed—including sacred milestones like friends’ weddings, my high school reunion, and my thirtieth birthday—to flip fish at the sauté station or sear steaks on the grill. I was grateful and a little surprised that we had pulled off the impossible: building a busy business out of a high-end restaurant in a tiny town. But I wondered how long I could keep it up, and to be frank, I wanted both more and less out of life.

Growing up on a farm, I saw what it looks like when people live to work. My dad ate, slept, and breathed the farm. Every facet of my family’s life orbited around tobacco, cotton, corn, droughts, and downpours, and by age eight, I vowed I would never be nor marry a farmer. Clearly, I didn’t know anyone who owned a restaurant, or I would not have jumped headfirst into a profession that’s arguably even more uncompromising. Unless a hurricane is coming and the cotton crop depends on it, farmers don’t work nights. Farmers get weekends, too, at least during the winter. That’s more than I can say for restaurateurs.

When the pandemic hit, the conundrum I’d created came knocking. For the first time in a decade, I couldn’t rush out to tend to a cookbook tour or show up for a shoot schedule. And at that point, my media career meant I was often fully removed from C&F’s daily operations, much less the kitchen. I took an unpleasant look at C&F’s upside-down situation and decided to close its doors with no thought of how it might reopen—not a popular decision. The Kinston community was furious, and to this day, many of them (erroneously) purport I’ve moved to Charleston, South Carolina, where I’m grateful to have two restaurants. Why else would I shutter a point of pride in our burgeoning town? My family argued that the restaurant was my legacy: I was shortsighted and full of hubris to close it. But my close colleagues and friends understood that my legacy was exactly what I was trying to preserve.

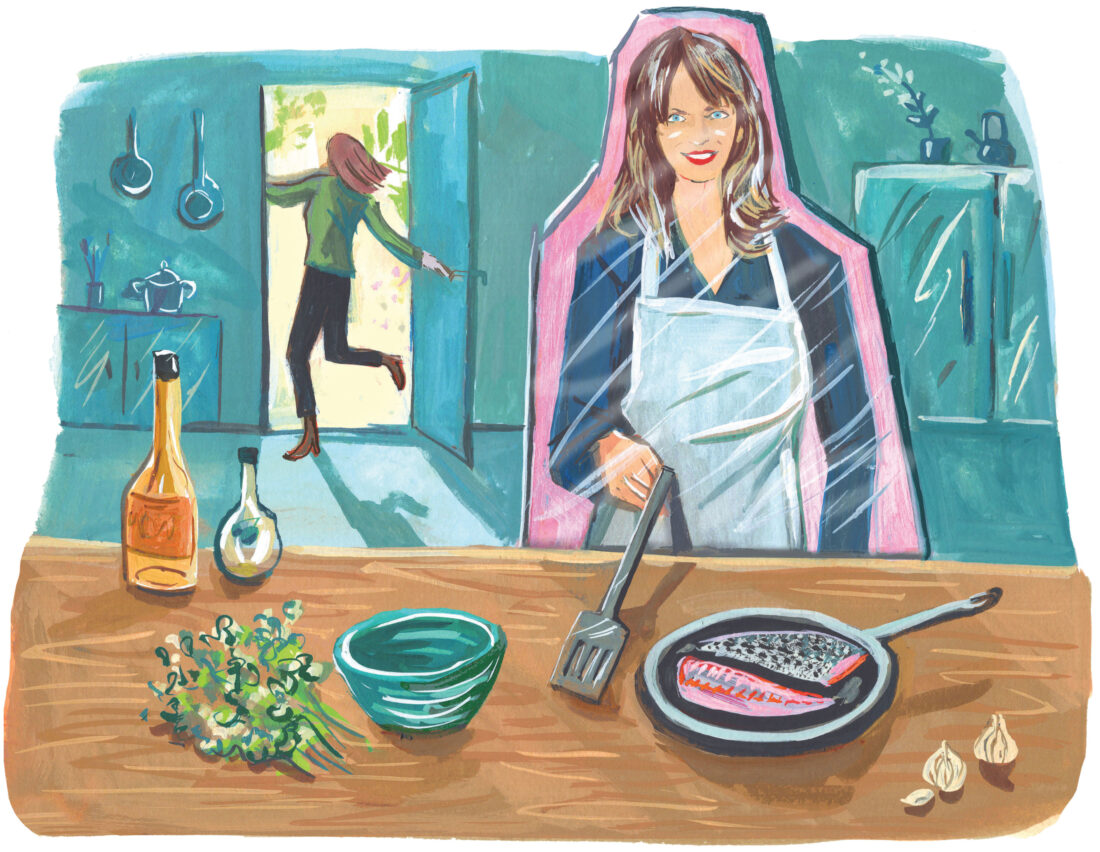

Reopening a restaurant often means bank loans, concept development, and lots of hiring. To reimagine C&F with me at the helm—eighty seats, six days a week—would require all of that and more. And as happens to so many of us midcareer, my priorities and desires had changed. I have a remodeling project I’m dying to tackle, a book I want to write, maybe even another promising TV idea. If I’m lucky enough to embark on any of those endeavors, I wouldn’t be able to hone plates on a daily basis in Kinston. Could I do something temporary, I wondered—something small but ambitious, with me at the center? Something that would help, too, with the financial burden of keeping the Kinston space? Would I even be able to orchestrate dishes or organize myself on that level anymore? Had being a chef on TV simmered me into a glorified home cook who only had digital tips and recipes to share? There was only one way to find out.

The former C&F has a beautiful, custom, new-to-me kitchen surrounded by sixteen seats—my inspiration. I planned three weekends of tasting menus between Thanksgiving and Christmas at what I would now call the Kitchen Bar at Chef & the Farmer. I told myself if the weekends were a bust, I would chalk the experiment up to the holidays and hope no one thought any more of it. But as I started dreaming up a menu of C&F classic dishes, reimagined through a modern lens, I became more and more excited. I was rediscovering my command and love of my craft—along with a healthy dose of something-to-prove.

The first Friday night back was really hard. I originally had grand designs for a one-woman show. I planned to dye my own napkins as well as paint, clean, and reconfigure the restaurant myself with the occasional helping hand from a friend or colleague. I accomplished all those feats but wildly misjudged how long they would take. I also forgot how many hours it required to prep sixty orders of anything. And I legit had to learn how to operate the custom range the restaurant had bought after I stopped cooking there.

You might say I had a lot of variables working against me. I shed actual blood while filleting a black bass and had to lean in to my charisma a little more than I had hoped. But Saturday was different. I was ready. I was present and proud of my food. I worked seamlessly with my team of three, and we served women who had watched A Chef ’s Life while in Siberia working for the Foreign Service. We also welcomed C&F regulars who used to feel like family. We hosted my parents to convince them I’m not crazy. It was all a joy.

I have a handful of weekends under my belt now, serving dishes like speckled trout with preserved tomato–crab gravy and stewed rutabagas with shallot chili crisp, with no designs on calling it quits. I like the rhythm of it: a project with planning and execution phases, a clear beginning, middle, and end. And I’m motivated by the transparency of it. With nary a sous-chef to hide behind, I am accountable—just not full-time.