Typically, a mid-summer hike in Central Virginia is not an experience that cools one down. Unless that hike incorporates the Blue Ridge Tunnel, a nearly mile-long, 165-year-old passage through Afton Mountain, situated between the nearby towns of Waynesboro and Charlottesville.

During the railroad boom of the mid-nineteenth century, the tunnel was a means to traverse the mountain gap that divides the state’s Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley regions, ultimately linking Richmond to the Ohio River. The Herculean task of building it fell to Claudius Crozet, a French immigrant who served in Napoleon’s invasion of Russia before becoming an engineering professor at West Point and chief engineer for the state of Virginia. Blasting with black gunpowder began in 1850 and was forecast to be completed in three years. The rock, however—especially the greenstone on the tunnel’s east side—had other ideas, its unexpected density causing delay after delay. (Crozet referred to hard rock ninety times in letters to government officials.)

It was brutal work. The tunnel was blasted largely by Irish immigrant laborers, including boys. At least fourteen perished in the tunnel from explosions and rock falls, and plenty more in the 1854 cholera epidemic. Though enslaved laborers weren’t allowed to handle explosives, that didn’t spare them, as several died while preparing the railroad bed for traffic. In 1856, the two sides of the tunnel finally met within inches of Crozet’s calculations. At 4,273 feet long, it was a triumph—the longest railroad tunnel in North America at the time. But sixteen more months were required to reinforce portions of the tunnel with brick and lay track. Criticism over the project’s slow progress caused Crozet to resign just three months before the first train loaded with dignitaries passed through his tunnel. Countless more freight and passenger trains followed until it was replaced in 1944 by an adjacent tunnel that could handle larger locomotives.

After the disused tunnel was donated to local government in 2007, a nonprofit foundation undertook the work to make it a public amenity. (Before the cleanup, curious interlopers would sometimes encounter curious bears inside.) Today, it sits five hundred feet beneath a convergence of I-64 and U.S. 250 at Rockfish Gap, just a stone’s throw from Skyline Drive, the Blue Ridge Parkway, and the Appalachian Trail.

Traversing the tunnel is an experience unto itself. On a recent morning, I arrive shortly after a rain to find runoff spraying over the tall, egg-shaped eastern entrance like a misty curtain. Just steps into the tunnel, the darkness is deep enough that I feel compelled to switch my headlamp to its brightest setting. (The tunnel offers no artificial light; a strong flashlight or headlamp is strongly recommended or you can’t even see your feet on the crushed gravel path.)

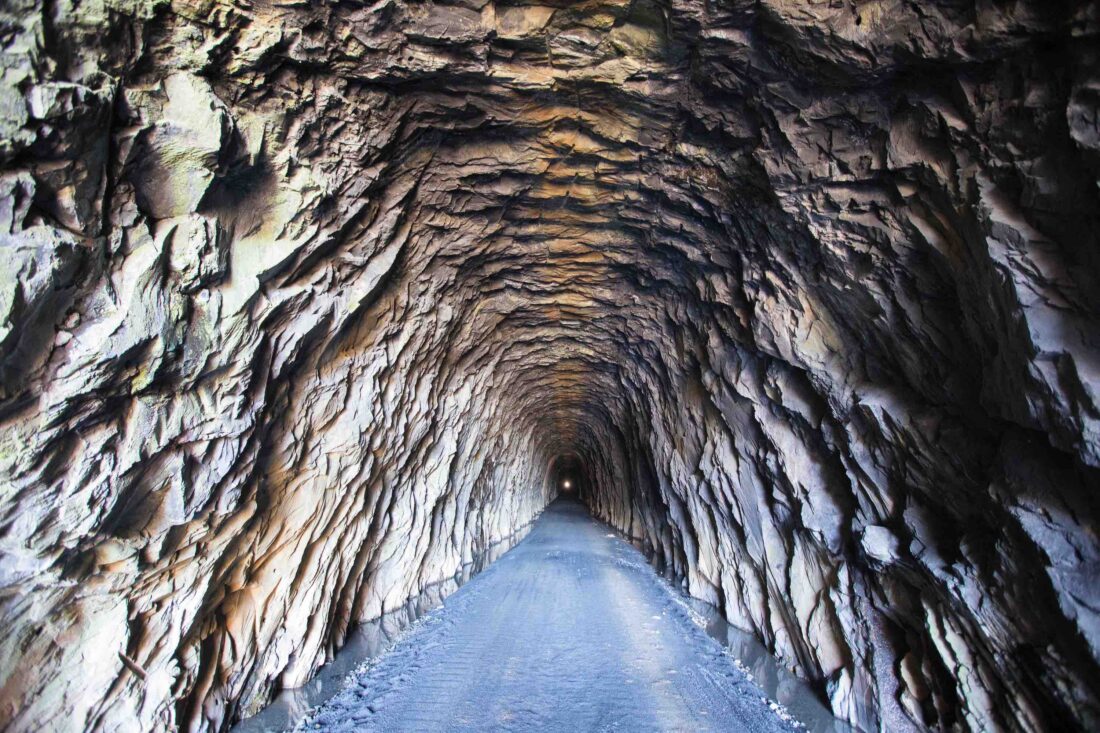

With the tracks removed, the tunnel can look and feel more like a cave, especially as your beam sweeps rippled crags of exposed rock. Though the summer heat and humidity are climbing outside, the tunnel grows cooler as I walk, dipping to maybe 60 degrees, and I’m thankful I’m wearing a light jacket. Near the midpoint, light from the ends—dim and distant even on sunny days—is non-existent. The silence here can be a tad spooky; break it with a shout and the resulting echo is dramatic. Another headlamp bobs from the other direction, and I can’t help but grin at being passed by a young couple casually pushing a baby in a stroller.

As the light from the western entrance asserts itself, one can better see that the last 1,400 feet of tunnel is still lined with red bricks laid long ago by hard, hazardous labor. The bricks are darker and smudgy at the apex, perhaps from the thick smoke belched by chugging trains that insisted on roaring through a mountain instead of over it.

The exterior of the western entrance is more formal, the tunnel framed by large blocks of gray stone and moss-festooned mountain rock. After the requisite selfie, there is nothing to do but retrace your steps, which are absorbed into the silence and shadows. The entire round trip, including the access trail from the parking lot, takes maybe an hour. But it feels as though you’ve been gone longer, emerging from an underground time warp.

A great way to re-acclimate is to take a minutes-long drive to any number of local eateries. Just to the west is Waynesboro, with brick-oven pizzas at Basic City Beer Company. To the east is Crozet (yes, named in honor of the tunnel’s engineer), featuring Fardowners pub and Mudhouse for coffee and muffins. Or head south onto State Route 151, home to many of the area’s most popular craft beverage makers, including Blue Mountain Brewery, Veritas Vineyard, and Bold Rock Hard Cider.