Food & Drink

Barbecue Road Trip: The Smoke Road

Photo: Peden + Munk

Jess shook his head, tapped his nose, and mouthed the words No smoke. But I insisted. How often do we get to Covington, Tennessee? I thought, as we pondered our third barbecue pit stop of the day. We might as well give their sandwich a shot.

My boy remained dubious. He stepped to the counter and asked the gentleman in charge how they cook their pigs. “With charcoal,” the fellow said. “Gets it tender, and the sauce does the rest.” Jess looked up at me with all the world-weariness a ten-year-old with a shock of blond hair and a snaggletoothed grin can muster. He didn’t have to say a word.

As we drove away, bound for the last stop on our semiannual road trip through rural western Tennessee—a region I’ve come to think of as a Land of the Lost for hickory-cooked pork barbecue believers, where roadside purveyors still fuel masonry pits with hickory and oak logs and undiscovered treasures always seem to lurk around the bend—I caught his eye in the rearview mirror. Jess smiled, shook his head, and tapped his nose again.

Jess knows barbecue. He ate his first solid food, a shoulder sandwich with slaw and sweet red sauce, in the parking lot of Spruce’s Bar-B-Q in Griffin, Georgia. Through the years, on family trips to Alabama, where my wife grew up, and Georgia, where I was born and raised, he’s learned to case a joint. In addition to working his nose, he knows how to survey the woodpile, ferret out freezer case menu conceits, and spot steam table pork at twenty paces.

Photo: Peden + Munk

The pork sandwich at Helen’ Bar-B-Q in Brownsville.

A couple of years back, Jess and I began to take just-the-guys jaunts north, from our home in Oxford, Mississippi, through the small Tennessee towns that sprawl between Jackson and Memphis. Jess discovered how to scan for armadas of martin houses, made from whitewashed gourds. He wondered, rightly, what really goes on inside tanning salons, twirling academies, and taxidermy studios. And he learned to eat, with discernment, intelligence, and gusto.

On one of those trips, I tried to get Jess to read the text of a historical marker, erected in tribute to some long-forgotten graybeard statesman. He feigned interest, as any dutiful son would. Five minutes later, he recovered his gumption. “What if I could play laser tag and you could get a really good barbecue sandwich in one place?” he asked. “That’s what we really want, right?”

Over time, Jess and I have learned each other’s palates. I’m a thin vinegar sauce guy. Jess likes molasses and ketchup-thickened concoctions. I prefer whole hog, pulled into long strands. Jess likes shoulder meat, hacked into shards and piled high on a white-bread bun.

More important, we have developed a shared love of western Tennessee barbecue and the people who cook it. As he grows from a goofball boy, who sings in the shower and hugs me good night, to a querulous teenager, who questions my authority and demands the keys to the family sedan, I hope we’re also honing an enduring friendship that won’t depend solely on blood and genes.

On our most recent expedition, Jess and I hit two stellar spots before that misstep in Covington. (We also did a drive-by of the Mindfield, a skyscraping folk art environment on the edge of downtown Brownsville, and made a quick tour of the Alex Haley Museum, an homage to the author of Roots tucked in a modest neighborhood in nearby Henning.)

Photo: Peden + Munk

Pit master Helen Turner.

Helen’s Bar-B-Q in Brownsville came first. Set in a metal hutch, on a hard curve north of the courthouse square, the six-seat café sits next to a retailer of discount jewelry and hair extensions. Across the street is a derelict tourist-court-style motel. Inside, Helen Turner, one of the few female pit masters in the South, stokes the fire and works the sandwich board. She’s a dervish. Behind the café, in a screened pit room, she burns hickory and oak down into coals between two sheets of corrugated tin. With a long-handled shovel, she slides those coals into a concrete block berth. After they spend ten to twelve hours in a swirl of smoke, she pulls pork shoulders from that pit, chops them with a cleaver, piles the meat high on buns, and douses all with a red sauce that straddles the line between ketchup and vinegar, between sweet and hot.

Jess ate his sandwich in four greedy bites. He moaned as he ate. Literally. But he also kept glancing up at Ms. Turner, who was wearing a blue floral-print hairnet and pink hospital scrubs. As she loped about the pit room, Jess watched. As he chewed through smoke-blackened hunks of pork flesh, his eyes tracked her movements. And his mind engaged.

Photo: Peden + Munk

Turner’s house sauce.

When we drove away, Jess was cradling a pickle jar of Helen’s sauce and plotting the many ways he could employ it when we got back home. His eyes were wide. And so was his smile. He got it, I told myself. I didn’t have to make some fatherly point about how women can do anything men can do. About how women work as hard as men. Ms. Turner had made those points for me. And she had dished a stupendously great sandwich, too.

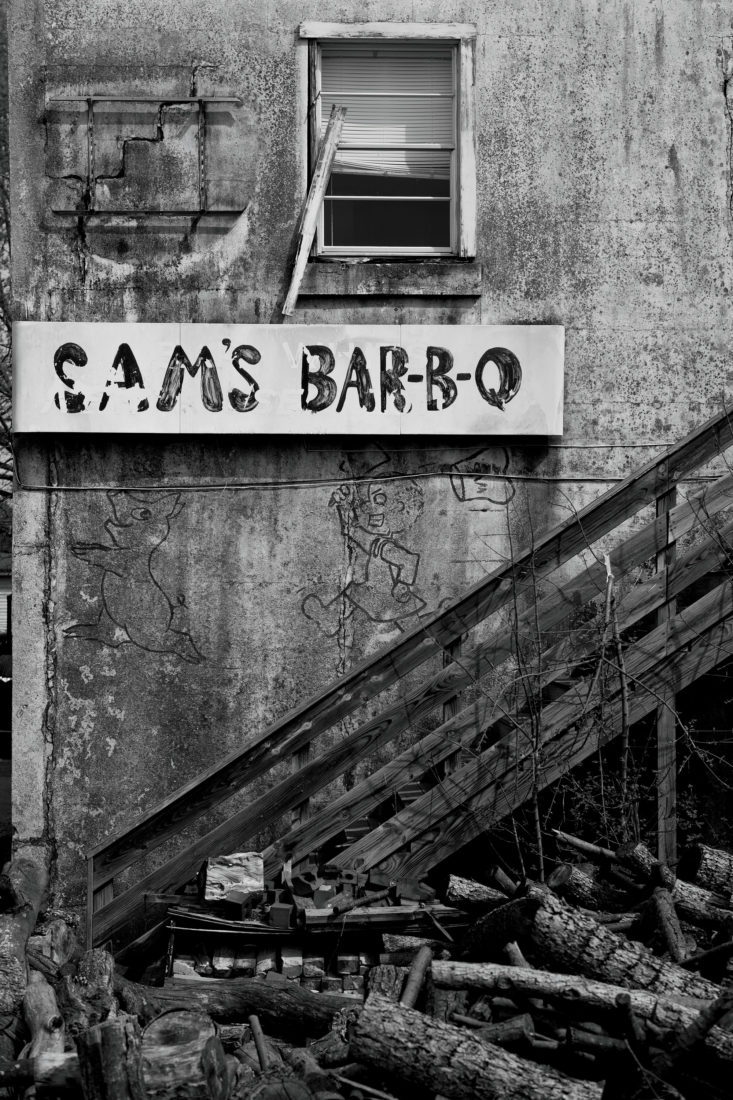

Sam’s Bar-B-Q in Humboldt was next. When Jess spied the woodpile, just south of downtown, he yelled for me to brake. A jumble of hickory trunks and oak stumps—delivered by friends and neighbors as they cleaned up from last spring’s tornadoes—that wood served as a kind of free-form art installation and a de facto advertisement that announced HONEST BARBECUE COOKED OVER WOOD HERE.

The building is made of white block, patined with soot. The pit, set in an adjacent building, is an iron-lung-shaped double-decker, with wood burning down to coals on the bottom and shoulders smoking on racks up top. It’s a feat of country-boy engineering, designed by the founder, Sam Donald, and now manned by his son-in-law John Ivory. The efficacy of that design gets proved every time customers heft a sandwich to their maw.

Photo: Peden + Munk

The woodpile outside Sam’s.

And that’s just what Jess and I did. We hefted two beautiful sandwiches and a slice of chocolate chess pie, still hot from the oven. And we listened as locals came streaming in. “Now, you’re the baby girl, aren’t you?” Mr. Ivory asked a woman who ordered a barbecue bologna sandwich. “Give me a sandwich with fatty meat and slaw,” said a fireman with soot on his hands.

Photo: Peden + Munk

Pit master John Ivory at Sam’s Bar-B-Q in Humboldt.

We could have stayed all afternoon, rubbing our bellies and listening to the dulcet tones of happy eaters. But we motored on, bound for Covington. Two stops don’t make a barbecue road trip, I told Jess. Three is the minimum. Everybody knows that.

By the time we left Covington, we didn’t need another sandwich. We had eaten well and often. But we pushed on. That’s what you do on a barbecue road trip. You push on, no matter how full you might be, goaded by the promise that the next experience might prove to be the best.

As rain began to splatter the windshield and night began to fall, we pulled into Millington, Tennessee. Our goal was Woodstock Store N’ Deli, a cinderblock rectangle where Anthony Bledsoe serves a green-hickory-smoked shoulder sandwich, piled perilously high and capped with slaw. He calls it the Sleeper.

The source of the moniker became clear when Jess and I stepped back into the gloam and spread paper towels on the hood of our station wagon. Our sandwich was an overstuffed behemoth. Fatter than fat. Stacked like a napoleon of meat, slaw, and sauce. Wretched and lovely excess. Enough to put any eater to sleep.

As we picked at stray bits of meat that had fallen from the sandwich and worked up the courage to take yet another bite, a woman approached us. She was stooped. And slight. She carried a ragged umbrella. Her hand was out. She said her belly was empty. She looked directly at Jess. I reached into my pocket for some cash. Jess folded the sandwich back into its tinfoil pouch and asked if she would accept it. She did. And then she was gone.

Photo: Peden + Munk

The Sleeper.

Five miles from home, I asked Jess what he learned on our barbecue road trip. “Respect what you have while you have it,” he said. That insight applies to issues of hunger and poverty. And to the barbecue traditions of the South. Not to mention father-son relations.

Though our barbecue buzz had faded by the time we rolled back into Oxford, my road-trip-fueled appreciation for Jess had grown, as had my conviction that we needed to plot another expedition. Before his hunger fades. Before he grows up.