Food & Drink

Black Moonshiners Get Their Turn in the Spotlight

This white lightning is Black made—and draws on the expertise of the South Carolina elders who once worked in the legendary but illegal moonshine trade

Photo: CLAY WILLIAMS

As a boy, Howard Conyers tagged along with his father, Harrison, to auctions and estate sales all across their native South Carolina. A longtime professional welder and farmer, Harrison might pick up a vintage washing machine at one stop, perhaps a pea sheller at the next. He’d often let his young son make the bids, directing Howard when to raise the paddle and when to let it fall.

In the early 1990s, Harrison, who is now seventy-two, joined a group standing around a machine at an auction. “I didn’t know what it was,” he recalls. “But the other fellows didn’t know either.” Harrison forked over ten dollars and took it home. A bootlegger friend then helpfully explained what the contraption could do: crush corn into meal. And with a heap of sugar, the right equipment, and a little discretion, that cornmeal could become moonshine.

Even decades after Prohibition, there was still money to be made in the open-secret liquor trade. In the Conyerses’ corner of South Carolina’s Pee Dee region, in Clarendon and Sumter Counties, “revenue men” and other authorities had never quite managed to eradicate illegal liquor making in tiny places like Pinewood and Rimini. And farming, always a risky profession, had never employed Harrison full-time. A hurricane or ravenous deer could doom a season’s corn, his extraordinarily flavorful sweet potatoes, his bottom line. He became a handyman to moonshiners, wielding his metalworking prowess to repair stills. They’d bring him components piece by piece until they trusted him enough to show him their distilling operations. He also began supplying them cornmeal, thanks to his new mill.

Preteen Howard ground bushels of that corn regularly and thought little of it—just another chore on the family’s now-eight-acre spread outside Paxville, where he’d tended his own patch of vegetables since he was six. He also dropped off large bags of corn at church for a fellow congregant who—he’s now fairly certain, in hindsight—was distilling “stump.” And he didn’t think to ask why milk jugs of clear liquid sometimes appeared in the family’s barn during overnight roasts of whole hogs for the Conyerses’ family barbecues.

That lack of curiosity was rare for a boy whose mother, Hallie, describes him as a “challenging little fellow” who overflowed with questions and politely but stubbornly demanded proof of the answers. But his father had perfected a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy when it came to moonshine—why worry about whether his cornmeal went to feed chickens or other people’s drinking habits?

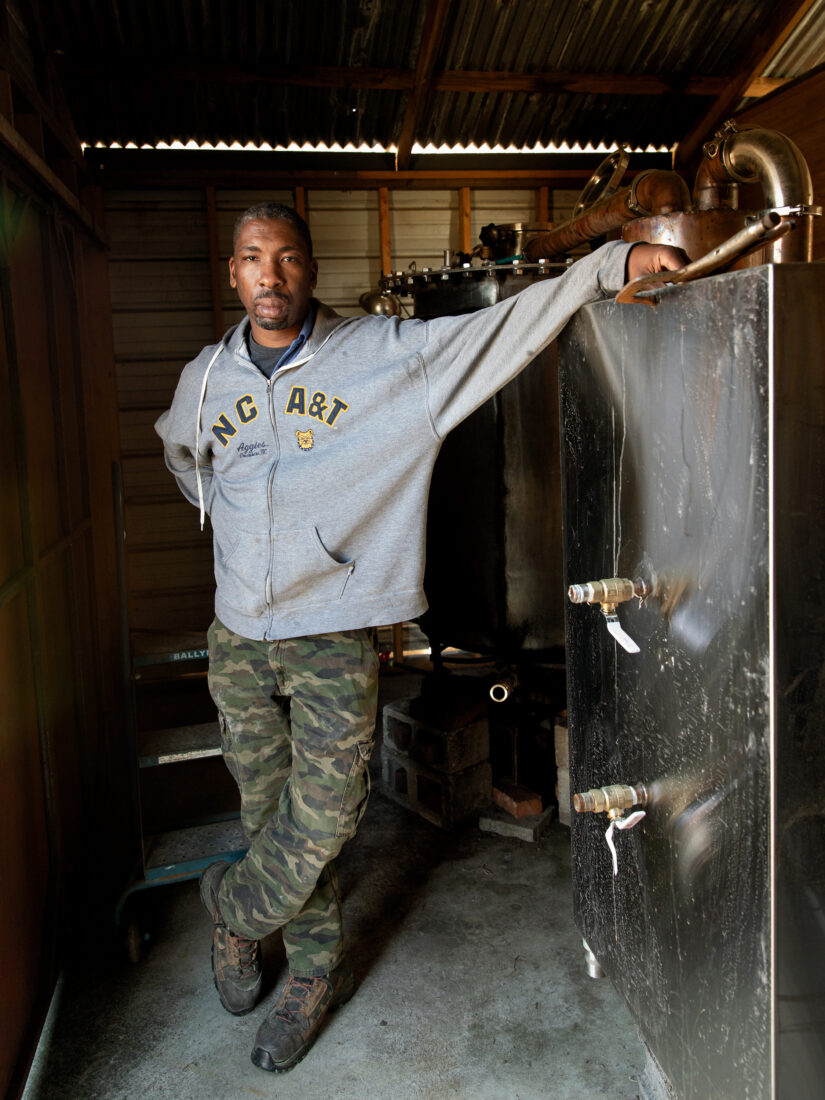

Eventually, Howard’s love of science and math took him to North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, where he studied agricultural engineering, with plans to work for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Next came Duke, where he earned an engineering doctorate, which landed him a job at NASA’s Stennis Space Center, outside New Orleans, as a literal rocket scientist. While in Louisiana, he’d barbecue whole hogs, just as his father did, to feed charity fundraisers and to uplift the overlooked tradition of Black pitmasters, a passion that resulted in his hosting the 2018 PBS food series Nourish.

Meanwhile, South Carolina had finally passed a law in 2009 allowing for microdistilleries. In 2015, Harrison read an article about the ensuing craft liquor boom and approached his son. What if they started their own venture, one that could operate in the sunshine and put some of Harrison’s corn-liquor knowledge—along with Howard’s engineering expertise—to profitable work? That’s how Backyard Distillery, one of the few Black-owned, moonshine-only outfits in the country, eventually came to be, at the height of the pandemic in 2020. Moonshine was now legit.

When people think of moonshine, they probably don’t envision makers like the Conyerses. They more likely picture Appalachian men with ZZ Top beards and overalls—like those with jugs marked “XXX” on the country-comedy show Hee Haw and in old Mountain Dew ads—or those who built NASCAR’s hot-rod prototypes to run liquor and elude the Man. The moonshiners of the collective imagination walk straight out of Deliverance, banjos twanging—white but darkened with the grime of life and the stigma of extrajudicial liquor. But they’re always white.

Despite the equally rich and varied distilling traditions of Black Southerners, the record of their contributions rests mostly in family memories and community oral histories. As part of Backyard Distillery’s mission, Howard, who’s now forty-two, is constantly chasing stories and recording oldheads who made the hooch. Last fall, while he was visiting Drefus Williams, a nonagenarian agricultural teacher who once worked in nearby Pinewood, his eyebrows shot skyward as Williams reminisced about the good-time house on his parents’ street in bordering Sumter County.

Photo: CLAY WILLIAMS

Harrison Conyers with sweet potatoes harvested on his farm.

“The Rock,” Williams recounted, “was known by Negroes far and wide. And it was known for its white liquor and its barbecue.” When the Rock reached capacity, latecomers hung out in their cars and bet on races, Chevrolets versus Fords. Drag racing, “drank,” and a pulled pork sandwich became the holy trinity of Black merrymaking.

The official accounts of African American moonshiners that do exist often involve law enforcement: newspaper articles about cops busting stills, a landowner snitching on his sharecropper’s “extracurricular” activities. In 1943, the University of North Carolina sociologist Sanford Winston and probation officer Mosette Butler published their take on the bootlegging problem in Eastern North Carolina, next door to the Pee Dee. Those moonshiners came “primarily from the sharecropper and tenant-farmer class,” whose seasonal work left hungry months. In the otherwise unidentified “Community A,” they wrote, “practically the entire Negro population years ago turned to the manufacture of liquor as an accepted source of livelihood.”

That also could have described Rimini. In the unincorporated Clarendon community, Richard Jefferson, who grew up there, his family, and friends erected a monument that includes depictions of a fish (for its wetlands) and a barrel. An outsider might assume the barrel references the town’s once-vital lumber industry, Jefferson says with a laugh. But anybody who really knows Rimini instantly understands it symbolizes the moonshine that accounted for (or padded) many a household income in times past.

Ignoring factors like white land ownership, separate and unequal schools, and Black disenfranchisement, UNC’s Winston and Butler blamed the Eastern North Carolina problem on poor soil: It forced young Black men—the majority of their sample, all arrestees—to seek out “anti-social” activity. The coauthors failed to realize that bootlegging was, to the contrary, a supremely social activity. During Prohibition in particular, Black moonshiners sold to both Blacks and whites, and illegal hooch flowed to city shebeens, white-only gentlemen’s clubs, plantations, juke joints, and country liquor houses. Not only that, but they coexisted mostly peacefully with the likes of churchgoers (many of them were churchgoers) and law enforcement.

Clarendon County experienced all of this and more. During much of the twentieth century, the county was overwhelmingly Black, with many working as sharecroppers for pennies on the dollar. In 1947, a farmer named Levi Pearson filed a petition for a school bus there for Black children, and in return, banks and other institutions blacklisted him. Other farmers who joined the NAACP found themselves unable to buy feed or gas on credit, so in 1957, a group of them organized the Clarendon County Improvement Association to help one another with small loans. In the 1980s, Harrison couldn’t get the time of day—much less a loan— from the local farm office, even as a property owner. Even now, when word got out about Backyard Distillery, a white resident told Harrison to his face that he hadn’t believed the elder Conyers “was smart enough” to make the moonshine venture happen.

But when he read about the craft liquor boom nine years ago, Harrison began envisioning another income stream—and another future. Given how small Black farms have often struggled to keep their operations afloat, “I thought it would be a way to generate wealth for generations to come,” he says as we sit talking in a farm shed. This plainspoken statement renders Howard—who can riff for hours on distilling tech and barbecue history—silent. “He never said it to me like that,” Howard explains later. “He said it would be a good thing for the family…and ‘I got a certain set of knowledge. Either [you could] get it or it could go to the graveyard.’”

Hallie Conyers, however, took some convincing. A career social worker, she’d witnessed alcoholism’s damage to her own family and her clients’. It took years for Harrison to admit to her that some of the corn their young son was grinding was destined for the still. “When I really found out [Harrison] was involved,” Hallie says, “I told him I was not going to jail about no moonshine.” She briefly fretted about what church members might think, because “we are trying to bring people to Christ, and making moonshine, we’re taking them away from it.” And she wasn’t thrilled about her beloved son—the former Boy Scout troop leader with impeccable educational credentials and a respectable job in the aerospace industry—getting caught up in a sometimes less-than-savory business.

“Is this what you’re going to do with your PhD?” Howard recalls her asking. So he arranged for his parents to tour several Kentucky distilleries. Hallie saw that making bourbon required chemistry, sanitation, marketing—and that many of the workers had degrees and weren’t ashamed about their vocation. She gave her husband and son her blessing.

She’s been known to change her mind on important matters: Raised on a farm, she once vowed never to live on one again—and then married a farmer.

On a crisp October day, Harrison stretches his long legs near a truckload of uncured sweet potatoes fresh out of the ground. His eyes crinkle with mischief as he recounts how once upon a time, in the Clarendon County seat of Manning, a woman operated a liquor house within a block of the courthouse. “The sheriff had to know,” he says.

Raids meant little. “If they bust you, and you had twenty-five gallons and got you selling it,” Harrison explains, “they’d claim they’d pour it down the sewage system in town. But that didn’t happen.” Law enforcement would shoot holes in stills—but often only into the easily resoldered kettle, he says, avoiding the harder-to-replace condenser.

Photo: CLAY WILLIAMS

An old-time handmade pot still, erected as a memento on the Conyers farm; Jimmy Red corn.

Substantiating such tales can be difficult—bootlegging produces as much lore as liquor. Take the stories about riderless mules trained to deliver supplies to remote stills, or the rumors about the local Piggly Wiggly. While cruising through Manning, Howard points out the grocery store. “I’d heard that bootleggers would pull to the back after hours,” he says, to load up on sugar—the sheer volume needed made large purchases a telltale sign someone was making ’shine. Then there was the Rimini family who worked as the moonshiners of record for a South Carolina governor. Or the brothers who locked their own stores of moonshine away from each other, betting blood was in fact not thicker than firewater.

Since firing up their outfit in 2020, the Conyerses have themselves occasionally quibbled about, say, the best way to fashion parts of the still—a largely lost art. But their strengths complement each other. Howard calls his father an expert in fabrication. Harrison’s mental blueprints informed their 240-gallon stills—tangible evidence of his big ideas—and his know-how allows them to tweak traditional methods for efficiency.

Howard, on the other hand, thinks in computer drafting languages, and oversees research and development for the distillery. He designed still parts to fit so snugly no vapors can escape, replacing the old-timey method of plugging equipment with dough. He’s stuffed a binder with copious notes on how to transmogrify mash into potent, safe “happy juice,” and whether the rare Cocke’s Prolific corn—an early nineteenth-century heirloom that had vanished before an Upstate farm rediscovered it—yields enough to make mash.

The Conyerses take pride in their traditional Pee Dee “cane and grain” recipe. The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, Howard points out, doesn’t recognize moonshine as a legally defined spirit type, so therefore distillers may label anything as moonshine. He likens Backyard Distillery’s product, then, to a “pasture-raised hog” versus a “commodity hog” raised by Big Pig.

As the pair have fine-tuned their hooch, they’ve recently relied on outside counsel, too, primarily from Matthew Dubose, a seventy-eight-year-old who’s retired from a soup factory, farming, and moonshining. The local legend advises the Conyerses on everything from how finely they should grind their corn to production times. “How long did it take you to get a batch done?” Howard asks. Three days, Dubose says, a full week less than it took the Conyers men during their earliest tries. His hack: swaddling the vats of fermenting mash in fuzzy pink insulation.

Photo: CLAY WILLIAMS

Firing the still; measuring alcohol by volume with a hydrometer.

Wearing a trucker hat low over his brow, Dubose tells his own story so softly I lean to catch the words. How much did you sell your whiskey for back in the day? I ask. “Well, I didn’t sell it,” he answers, with a small smile. “It was gifts.” I note the former bootlegger’s reticence, and I recall that Howard asked me if his father could face legal punishment as an accessory to moonshiners, even all these years later. I rephrase my question, leaving out that implicating “you.” He promptly answers: Six dollars or so. He’d learned the trade from his father, a swamp fox who could read directions in the leaves and the slant of the sun. The elder Dubose worked as a farm laborer, but his fourteen children had to eat. So he also ran a liquor operation near Rimini, tucking stills in the wilderness where duck hunters and paddlers now roam the Sparkleberry Swamp. Some of the Dubose children, including Matthew, helped tend the operation, often set deep in the woods to avoid detection.

After all, there was a national crackdown happening. By the early 1960s, federal, regional, and local agents had launched “Operation Dry-Up,” arguing that moonshine constituted a public health threat, and targeted South Carolina first. In 1965, the Sumter Daily Item ran ads with crude hand-drawn skulls and bones, warning readers to avoid the scourge of white poison—bootleggers sometimes used radiators that leached toxic metals. Other publications described habitual moonshine drinkers in terms like those used to characterize meth users today: “Their lips bleed, their skin shreds, sores pop open on their bodies, and they spend their nights vomiting up parts of their insides.”

The feds enlisted hometown heroes and TV lawmen to their cause. Bobby Richardson, a Sumter native and Yankees second baseman, featured on a radio spot about the evils of homemade drink. Raymond Burr, TV’s Perry Mason, intoned in an ad, “On my television series, I am confronted with the problems of the innocent and the guilty. Today let’s talk about the guilty. Did you know that in your community killers are poisoning people?” Andy Griffith—the smiling sheriff without a gun in fictional Mayberry, North Carolina—added his two cents. “Now, you might have some funny thoughts” about moonshine, he chided, “or even laugh it off sometimes.” (Never mind that his eponymous show had played moonshine for giggles.)

By the late sixties, national authorities had “put a big cork in the bottle” of moonshine production. Or so they claimed. But in the backwoods, many carried on. In 1982, for instance, cops uncovered a still within five blocks of downtown Sumter—the woody air wafting from a neighboring plywood factory had supposedly masked the distinctive warm, yeasty scent.

To avoid getting busted themselves, bootleggers like the Duboses had to show a little ingenuity. At one point, Matthew’s family constructed a still that floated on a raft in Sparkleberry Swamp. “You put enough mud [underneath the fire],” he explains, “that the wood wouldn’t burn.”

Even so, in 2007, Dubose made front-page news when he was arrested on charges related to a moonshine operation unlike any other ever seen in Sumter County. In the shadow of Milford Plantation, one of the country’s finest antebellum Greek Revival mansions, sheriff ’s deputies had found a buried fifteen-by-twelve-foot bunker storing five hundred pounds of sugar, thirty gallons of finished white lightning, and enough mash to brew another hundred. The Sumter newspaper reported that a hose ran straight to Dubose’s former house. The police had followed a tip (and the aroma) to the hidey-hole.

Dubose bristles at the suggestion that cops could have smelled the operation. The pipes that funneled the fumes outdoors had been rigged to run up towering trees to discharge above nose level. That kind of bootleg construction might attract notice elsewhere. But here, among tractors rumbling down two-lane roads, no one blinks when a backhoe scoops great chunks of clay from the earth.

Photo: CLAY WILLIAMS

The finished product; father and son on the farm.

Talking to men like Harrison Conyers and Dubose, you begin to understand why moonshiners have become folk heroes of a sort—hardy, independent, able to coax income and pleasure from the most inhospitable environments. “People don’t realize it was not easy work,” Howard says as he drives his pickup through the countryside. You had to be part lumberjack, part chemist, and always a sentry: cutting trees to keep old-fashioned still fires going, lugging propane into remote areas, dodging the law, making liquor that was illegal but safe. One day, he asked Dubose, “What happened when it started lightning?” Dubose shrugged off the idea of toiling near a big metal pot in an electrical storm: “We keep going.”

“We keep going” might well be Backyard Distillery’s motto, too (though its official slogan is “the smoothest stump in the South”). Howard points out a few fields with decrepit tractors or desiccated cornstalks. He moves between tenses when talking about the area’s Black farming families: present for the ones who remain, past for the ones who sold their farms, conditional for the ones on the edge. Sometimes he leaps into the future. He’s moved back to South Carolina from Louisiana, and he aspires to own a hundred acres around his family’s homestead.

In the meantime, he and Harrison will keep building Backyard Distillery, selling their two moonshines, regular and barrel aged, along with the occasional seasonal offering—rye, sweet potato, Jimmy Red corn, and soon, perhaps, muscadine—in tiny plastic milk jugs that mimic the larger ones Black moonshiners of yore reused to hold their hooch. Right now, their sales are limited to their farm, where they regularly open their doors for the public and for by-appointment pickups. But the Conyerses know this: In Clarendon, other South Carolina counties, and beyond, they will herald the history of Black makers wherever their white lightning strikes.