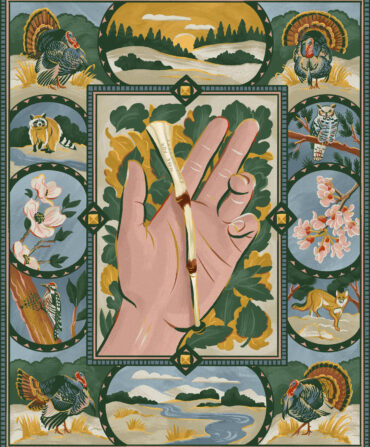

Land & Conservation

Bluegill Dreams

For a good chunk of my youth, this boy from New England was a Southerner at heart. I had fallen in love with largemouth-bass fishing and what is known as panfishing. The most renowned practitioners had Southern accents and called big fish hogs and bubbas. My heroes haunted ponds with cypress knees; their faces smiled from the pages of the Bass Pro Shops master catalog—which from when I was nine to twelve years old might as well have been my Bible. I knew every colorful lure by name—Jitterbugs, Tiny Torpedoes, Rat-L-Traps—and the names of all the pro bass fishermen, Dance, Lindner, Hannon, Martin.

Around age twelve I started seeing my mom again after a three-year absence. She’d left my dad and disappeared. Mom would come by the house once a week to pick me up and spend an afternoon with me. By my request, our outings consisted of going to a bait and tackle store. She would patiently walk the store with me as I looked wide-eyed at all the lures and rods and reels and then, before we left, she would buy me a lure of my choice.

I fished local farm ponds and golf-course ponds, and in drinking-water reservoirs posted with NO TRESPASSING signs. I caught small-mouth and largemouth bass and those panfish—crappie, pumpkinseed sunfish, and bluegill sunfish. As I cast from grassy and rocky shores, I dreamed of one day owning a Ranger bass boat like the pros used, with a carpeted floor and compartments to hold all my tackle boxes. Plastic lures and baits and jars of pork rinds would be scattered all about the deck. And this held as a vision, a salvation even, until slowly but surely my love of trout and fly fishing grew to such an extreme obsession that it pushed all that stuff to the side.

But that part of me that wanted to catch big bass and panfish (a bass over eight pounds or a bluegill over one pound, thresholds for any self-respecting angler) never really left my soul.

Last Spring I was in Raleigh, painting several murals as part of a survey of my works at the North Carolina Museum of Art. At some point it occurred to me that I was in the heartland for the warm-water species I loved as a child. And damn if that bass-and-bluegill-loving side of me didn’t come raging out. One night in my hotel room I entered the words “big bluegill” into Google, something that hadn’t been possible when I was nine in a pre-Internet world. I soon discovered a society of bluegill fanatics unlike anything I could have ever imagined.

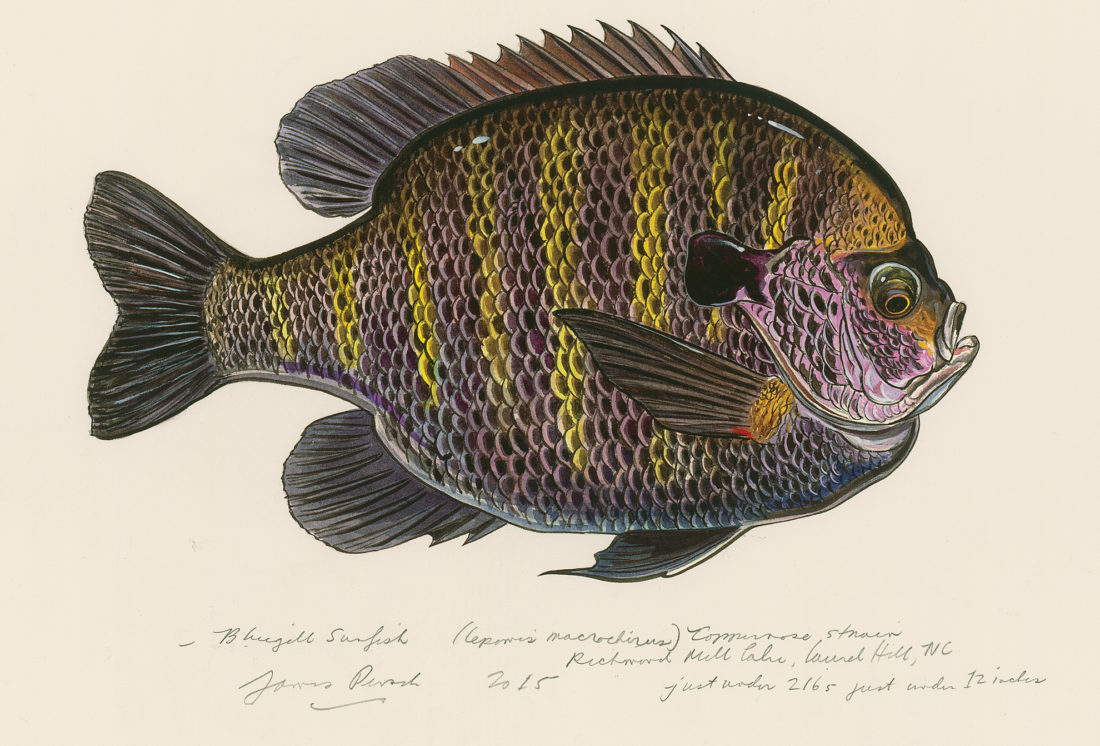

Fish in the sunfish group—redbreast, pumpkinseed, bluegills, and some others—are often the first that anyone catches on a rod and line. They can also be stunningly beautiful, with rich streaks of orange and blue and turquoise, hints of red and black and deep ocher, sienna and umber. For a person who loves fish and loves to paint fish, they are remarkable. They fight hard for their size, so are admired among anglers for their bulldog tenacity. They are forgiving and are good teachers for a budding fly fisherman. One could say that they are the ultimate ambassadors from a mysterious netherworld—a liaison between above and below the reflective water’s surface.

There was something indulgent in this Googling, some failing in my focus on the present, some giving in to nostalgia. Like surfing the great Web for traces of a first love. Was it okay to go back? Should I take this time machine back to thirteen? Would she, I mean, the fish, look the same or mean as much to me? Wasn’t part of the magic in the fantasy—me and the big bluegill—that it remain unconsummated?

What would it be like to behold a big bluegill? Does knowledge of something kill the beauty in unknowingness? John Keats famously remarked that Isaac Newton, by showing the mechanics of how white light could be fragmented through a prism into a color spectrum, had destroyed the mystery of the rainbow. In his poem “Lamia” he likens Newton’s gesture to unweaving the rainbow. Would catching a big bluegill kill the poetry of my childhood?

Naw—I wanted to catch a bubba!

Back I went, time and again, to bigbluegill.com, described as “a network for bluegill fans and people who love big bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus).” The site teemed with enthusiasm, and also new knowledge for me. For instance, I had never known that there was a distinction between a northern bluegill and a southern strain called a coppernose. The coppernose actually did have a golden-coppery blaze on the top of the head. I could see it clearly in many of the pictures. So what exactly would count if I wanted to achieve my goal of catching a bluegill over a pound? In choosing a location to catch my personal record, I had to beware of hybrid sunfish. There is now a widely disseminated sunfish that is a cross between a green sunfish and a bluegill. That wasn’t going to cut it—they grew faster and bigger than pure-strain bluegill. But over and over in my research I kept encountering enormous pure-strain coppernose bluegills from the same location. It was called Richmond Mill Lake, near the town of Laurel Hill, North Carolina, less than two hours south by car from Raleigh, where I was working at the museum. This was too good to be true.

Richmond Mill Lake is located on a private three-thousand-acre property called King Fisher Society, now run as a resort for hunting and fishing. I was returning in the summer to lecture at the museum and arranged with the owner of the Society, Jim Morgan, to spend a day bluegill fishing on his lake.

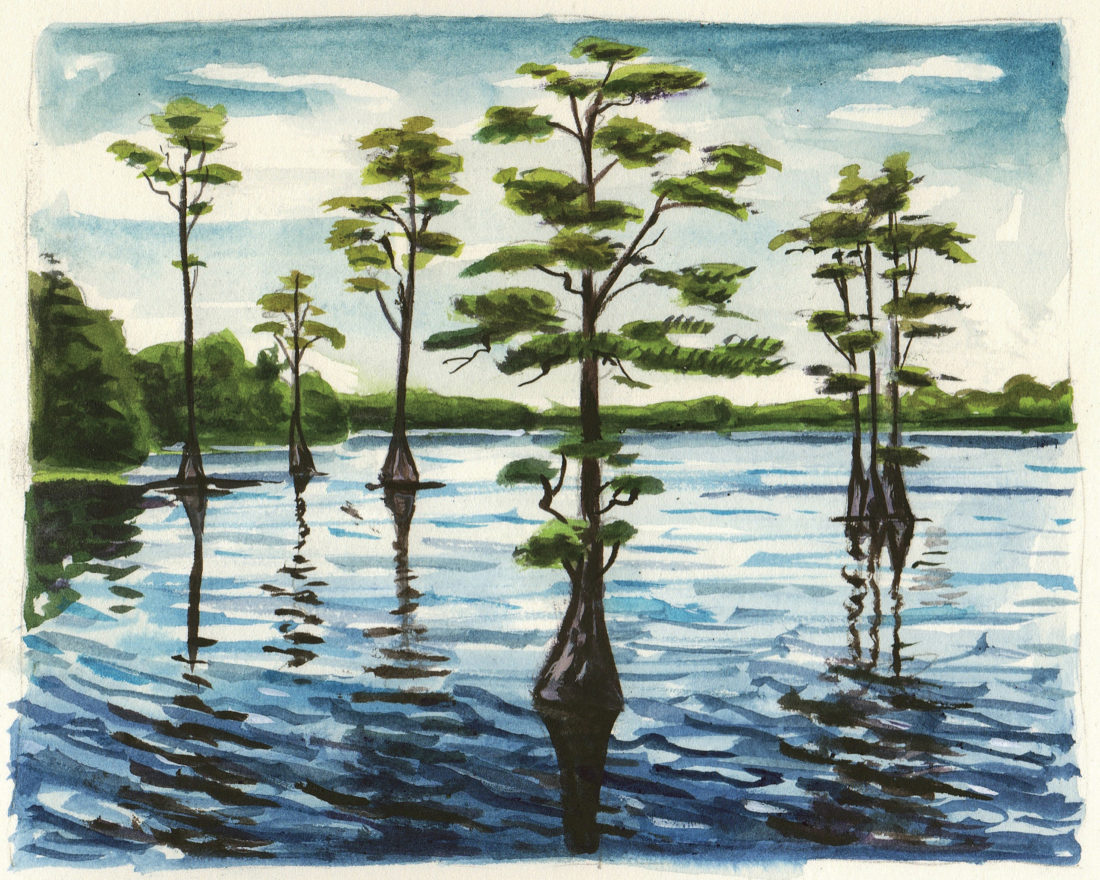

Now, to bluegill fanatics, King Fisher Society would be where they go to die. Somehow I’d always pictured catching my big bluegill in a farm pond, a one-acre puddle surrounded by cows. As I approached where I would be staying the night, I have to say, it was not what I expected. I’m not sure I’ve seen a prettier lake anywhere in this country. Pond cypresses with emerald-green leaves stood in the water like old sentinels. Morgan told me that some were several hundred years old. It was an impounded cypress swamp, he said. The first dam was built in 1835, a decade before Texas became a state. The beautiful house, now a guest cottage, had belonged to his bachelor uncle. The business had been started in part to pay for the construction of a new dam on the lake.

Morgan had arranged for me to fish the next day with one of the best guides in the area, certainly the best bluegill guide, he said, Robbie Everett. All I had to do was watch the lights dim in the sky and the pond slip behind the veil of night, the cypresses in silhouette, the frogs a-peeping. I was so excited I couldn’t fall asleep. I poured a little bourbon from the bar and sat in the screened-in porch. The air was a bit warm and heavy for June, I’d been told. To me it felt just right.

Everett met me at the dock in the morning in his chariot. It was a bass boat, just as I’d dreamed of when I was a child—the sparkly painted hull; the carpeted deck; tons of compartments stuffed with tackle boxes full of lures; a bucket of live crickets for bait; a cooler with drinks, food, and a can of worms; a trolling motor in the bow; swivel seats; several spinning and bait-casting rods rigged up and ready to go. What did I do to deserve such bounty?

The temperature had never dipped below eighty the night before, and Everett said daytime highs would exceed a hundred. It didn’t take me long to realize he was already apologizing for the conditions. He suggested that catching a big bluegill was certainly possible today, but it would be tough. This, of course, was fishing.

But the morning light was soft and orange-pink, the haze was gentle, and bobwhites were calling from the hillside beneath a grove of longleaf pines. I would start with a fly rod, casting a small popping bug, and Everett a jig with a plastic grub.

Besides guiding, Everett did some tournament bass fishing (he had been a pro bass fisherman for fourteen years, starting at fourteen) and also ran a family bait and tackle shop. The shop sells extinct lures that people decide they want ten years after the manufacturer stops making them. He handed me his business card. It smelled like bait.

“Are there other ponds in the area with big bluegill?” I asked Everett.

“Not like this,” he said.

“What is it about this lake?”

“Something about ten thousand gallons a minute pushing through here, the old creek bed, and the acidity of the lake. Bob can’t put a finger on it.”

Bob was Bob Lusk, a biologist who manages ponds all over the South. He is nicknamed the Pond Boss. Pond management at this level is something relatively new. At intervals around the lake were boxes on posts that almost resembled wood duck nesting houses. They were well hidden but became visible as we moved quietly around the lake powered by the trolling motor. Every few hours, pellet food from the boxes was dispensed in a tight radius around the box, all on an automated system. Whoa, wait a second, I thought. These fish were being fed pellets?

Everett explained to me that the pellets were for the largemouth bass. Most largemouth bass will not eat artificial pellets. The pellets are specifically for bass that are stocked in the lake called feed-trained bass. How do they make a feed-trained bass? They produce a bunch of bass fingerlings in a hatchery and start offering them pellet food. Only a relatively small percentage of the fish will eat pellets. Those fish are separated, raised, and eventually sold and stocked in ponds like these with feeding stations. Feed-trained bass can grow so fast on a pellet diet that the growth of their bodies outpaces that of their mouths.

I wasn’t here for bass, though. I was here for the big bluegill. But now a tangle, a twist had been inserted in the golden rope that was my fantasy. Were the bluegills big because they were feeding on residual food that the fat bass missed? If I caught a big bluegill, would it count? Was this cheating? Was it an artificial experience? Should I feel dirty?

Everett assured me that even though the bluegills did probably feed on bass food scraps, hundreds of other ponds in the South now had pellet feed dispensers blowing food into the water, and the bluegills in those ponds did not get nearly as big. That’s why this place confounded the Pond Boss—how the hell did these bluegills get so big? Everett told me that the year before he’d caught one three pounds. He showed me a picture on his Facebook page. A three-pound bluegill?

Just then a fish hit my little popping bug. It tugged and swam in spirals. It was like fighting a dinner plate; the fish used its surface area to its advantage. Everett put the net under the fish. He lifted it out and weighed it on a small scale. One and a quarter pounds! My first bluegill in the lake was by far the biggest I had ever caught. I had passed my personal objective, fulfilled the fantasy—surpassed the one-pound mark. How did I feel? Not satisfied at all. I wanted a bigger one—if for no other reason than that now I knew there were much bigger ones in there.

We made our way up the lake to where it gets smaller and the river comes in. Everett told me we were in the northern range of the alligator and a few were occasionally seen here. There were bowfins in this lake, too, a fossil fish that hasn’t changed much in more than a hundred million years. No one put them there. We watched a heron fish and an osprey dive and catch a bass. A bald eagle flew by. Managed or not, it felt wild here.

Everett slowed down the boat as we started to cast up against a beautiful grassy bank. Wakes and swirls made by fish disturbed the shallows. “I smelled ’em again,” he said in his Carolina drawl. “A little faint, not super strong.”

“You can actually smell them?” I asked. I thought he was joking.

“Yes, sir.”

In the South, bluegills spawn from spring to late summer, and seasoned anglers can smell them on the beds. A sweet smell. It was nice to know he was using all his senses.

Everett genuinely wanted to help me catch a bubba. Now we had a little breeze, which he said was good. There was a chance I could get a fish close to two pounds, he said. That kind of blew my mind. Everett had certainly brought the whole arsenal. He cast what he called a “Creamsicle grub” but said he might switch to a bobber and cricket.

“When you’re specifically trying to get a real big bluegill,” he said, laughing, “sometimes you got to try a lot of weird shit.”

By 11:00 a.m. it was a hundred degrees. The sun was relentless. Everett said this was very unusual for June. I didn’t buy it. I knew it was hot down here in summer and I’d expected it, but it was still surprising to see how much sweat was pouring out of my body. Everett switched to a worm. I grabbed a bottle of water out of the cooler and drank the whole thing in five gulps. We gave up casting to the banks and started throwing bait at the bulbous stumps of the cypresses. Everett got a strong tug and soon brought in a fish that looked obscene. Its head had a series of humps on it from just being big and badass. He hung it on the scale by the mouth. He showed me where the line hung at the two-pound mark. It was so fat its scales were popping off of its body, like the buttons on a man’s shirt after a big meal. My mouth was agape as he let it back into the water.

“Are you serious?!” I said aloud, wiping sweat from my face.

Throughout the day fish in the range of 1½ pounds were common. All were about eleven and a half inches. Some were dark colored, some light. Some had beautiful vertical bands of brown, green, and yellow with pink and copper on their faces. We caught a lot of nice bass, too, both wild—ones that had hatched in the lake—and stocked feed-trained bass. Every time I put my hand in the water to let a fish go, I couldn’t believe how warm it was—in the mid-nineties.

Toward afternoon Everett could see that I really wanted a bluegill like the one he’d caught. But in the heat I was fading fast. It didn’t hit 103 degrees as they’d predicted, but it felt like 114 in the sun. By 4:30, I was ready to pack it in. Everett said, “Let’s go through the stumps one more time.” I took my last cast up against the base of a cypress stump not far from the dock where we’d launched that morning. I hit the tree with my hook and worm, and let it slide down until it hit the bottom. There, in the dark tannic water, it was met by a hard jerk. The big fish bent the rod. I was certain it was a four-pound bass. Instead, it was a bluegill, fish of my youth, fish of my dreams. And a monster. Everett netted it and we weighed it. Just short of two pounds. We measured it. Just short of twelve inches. I let it go. Was I happy I’d indulged this fantasy? Hell yes.

That night, Morgan treated me to stories and local history over a beautiful dinner of grilled lamb chops with a good deal of wine and bourbon. He was a former minister and a jazz musician, and he’d had a friend come play for us on the piano by the screened-in porch. We watched the light change over the cypresses, mirrored in the still water of the lake.

I asked how the place got its name. Morgan said that growing up here, he and his friends had a secret fishing club. They named it after a common bird you see fishing alongside you, the blue, white, and black belted kingfisher. The King Fisher Club was unusual in the segregated South; the members were from different walks of life and were different colors. That didn’t matter at all to them, especially when they were out on the water, fishing for the generous, omnivorous, fun-loving bluegill. Only partway through Morgan’s childhood did the schools get desegregated. “We were so happy we got to go to school with all our fishing buddies,” he said.

In the end it wasn’t about the bluegill, or the fishing at all, I suppose; it was about meeting and spending time with guys like Everett and Morgan—seeing a beautiful place that I had never known existed. Bluegills had brought us all together. Thank you, bubba.