Jim Godwin: Turtle Powerhouse

In Alabama’s biodiverse waterways, an aquatic zoologist pieces together the secret lives of reptiles

Photo: Mac Stone

Jim Godwin with the hoop nets he uses to catch snapping turtles, in Alabama’s Talapoosa River.

Affiliation: Auburn University’s Alabama Natural Heritage Program

Location: Auburn, Alabama

Ask Jim Godwin what he does for a living, and he’ll make it sound as if he spends most of his time cruising Alabama’s rivers in search of turtles. Ask anyone who works with him, and they’ll tell you he is the driving force behind mapping out ranges, conducting surveys, and providing a vital baseline of knowledge for all manner of species in this global hot spot for turtle diversity, all essential data in a time when the reptiles are declining worldwide.

As the aquatic zoologist with the Alabama Natural Heritage Program at Auburn University—a position he’s held since 1992—Godwin has pieced together grants to study and conserve mussels, fish, salamanders, and snakes (he led the effort to reintroduce the indigo snake in the state). Along the way, turtles became his abiding passion. “They just have a fascinating architecture,” says the Arkansas native. “Here is an animal that has developed a body plan where it lives within its rib cage.” And it probably doesn’t hurt that Alabama is the best place to study them—more turtle species (thirty-one) live here than anywhere else in the country. Yet the combined punch of pollution, sedimentation, damming, boat strikes, and abandoned fishing lines threatens many of them.

But to know how to conserve a species, you first have to understand where it lives and what it needs, and that’s where Godwin comes in. Take the federally endangered Alabama red-bellied turtle, a specialized and secretive denizen of Mobile Bay’s streams, rivers, bays, and bayous. Through painstaking trapping, Godwin has helped establish the turtle’s range and is currently gathering critical data on its overall numbers and the flow of genes between the remaining populations. The flattened musk turtle, a species equipped with a compressed shell that helps it slip into rocky crevices, resides only in Alabama’s Black Warrior watershed. Godwin helped identify the turtle’s last stronghold, in Bankhead National Forest, plus locations where it once thrived, laying the groundwork for restoration work.

Photo: Mac Stone

One of Godwin’s finds, a male yellow-bellied slider.

Godwin’s personal favorite is the alligator snapping turtle. He cruises rivers like the Choctawhatchee, setting hoop nets with live fish as bait, hoping to attract one of the fifty-pound prehistoric creatures (“They’re never happy to see me”). Once one is in the boat, Godwin takes tissue samples to assess the genetics of different populations, and marks each specimen so if it’s recaptured, it can yield such valuable intel as its home range and age. “When you pull one up, it might be older than anyone in the boat,” he says. “Like all turtles, this impressive, ancient species is a unique part of these rivers and of the natural heritage of the Southeast.” —Lindsey Liles

Raz Halili: Oyster Heir

Gulf Coast bivalves have a better chance with this second-gen oysterman at the helm

Photo: NATHAN LINDSTROM

Raz Halili with fresh oysters at his Pier 6 Seafood & Oyster House in San Leon, Texas.

Affiliation: Prestige Oysters Inc.

Location: San Leon, Texas

Raz Halili’s earliest memories are of riding along on an oyster boat, the smell of salt water and diesel fuel mingling at Redfish Island off the San Leon Peninsula in Texas. By his teens, he was out oystering himself, helping his father, a Kosovar immigrant of Albanian descent, and his mother, a native Texan, build their burgeoning company, Prestige Oysters Inc.

Some three decades later, Halili and his parents now run a Prestige that looks very different: The outfit’s thirty-five boats harvest some million oysters annually, year-round, from fifty thousand acres of waters along the coasts of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and into Florida. The bounty pops up in restaurants nationwide, and even in Whole Foods and Publix. But for the Halilis, their success hinges on giving back to the Gulf. “If you’re looking for the type of relationship with Mother Nature where you take and take and move on, eventually there will be nothing left to take,” Halili says. “My dad understood that early on.”

Compared with historical estimates, wild oyster reefs have declined by more than 50 percent in the Gulf due to dredging, pollution, sedimentation, overfishing, and hurricanes. “Oysters are a keystone species,” Halili says. “They filter our water, they offer a habitat for so much other life, and they’re the first barrier against storms and coastal erosion.” That’s why in addition to returning recoverable shells, as the company has done since its inception, Halili went a step further in 2009 and began putting limestone and cultured concrete in the waters Prestige works as a substrate for oyster spat to latch onto, to form new reefs—know-how he has exported for ensuing restoration projects at Carlos Bay and other Gulf spots through contracts with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission.

In 2017, Halili threw his support behind the closing and conversion of a sensitive oyster reef in nearby Christmas Bay into a sanctuary; that year, he also invited the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) to audit the business. After an arduous three-year process, Prestige became the first and (still) only wholesale fishery in the Americas to achieve MSC’s certified sustainable badge. Also in 2020, he manifested his tide-to-table vision by opening Pier 6 Seafood & Oyster House, near Prestige’s offices in San Leon. Just two years later, the James Beard Awards named Pier 6 a semifinalist for Best New Restaurant. Fish Company Taco in Galveston followed in 2024.

His restaurants’ oyster shells are, naturally, ear-marked for a cause, too: Last spring, thirteen hundred discards were cured and scattered on the floor of Galveston Bay to form the foundation of Rett Reef—a no-harvest sanctuary reef created in partnership with the Nature Conservancy. “We’re always thinking about the future,” Halili says. “We want oyster reefs and healthy bays for centuries to come.”—LL

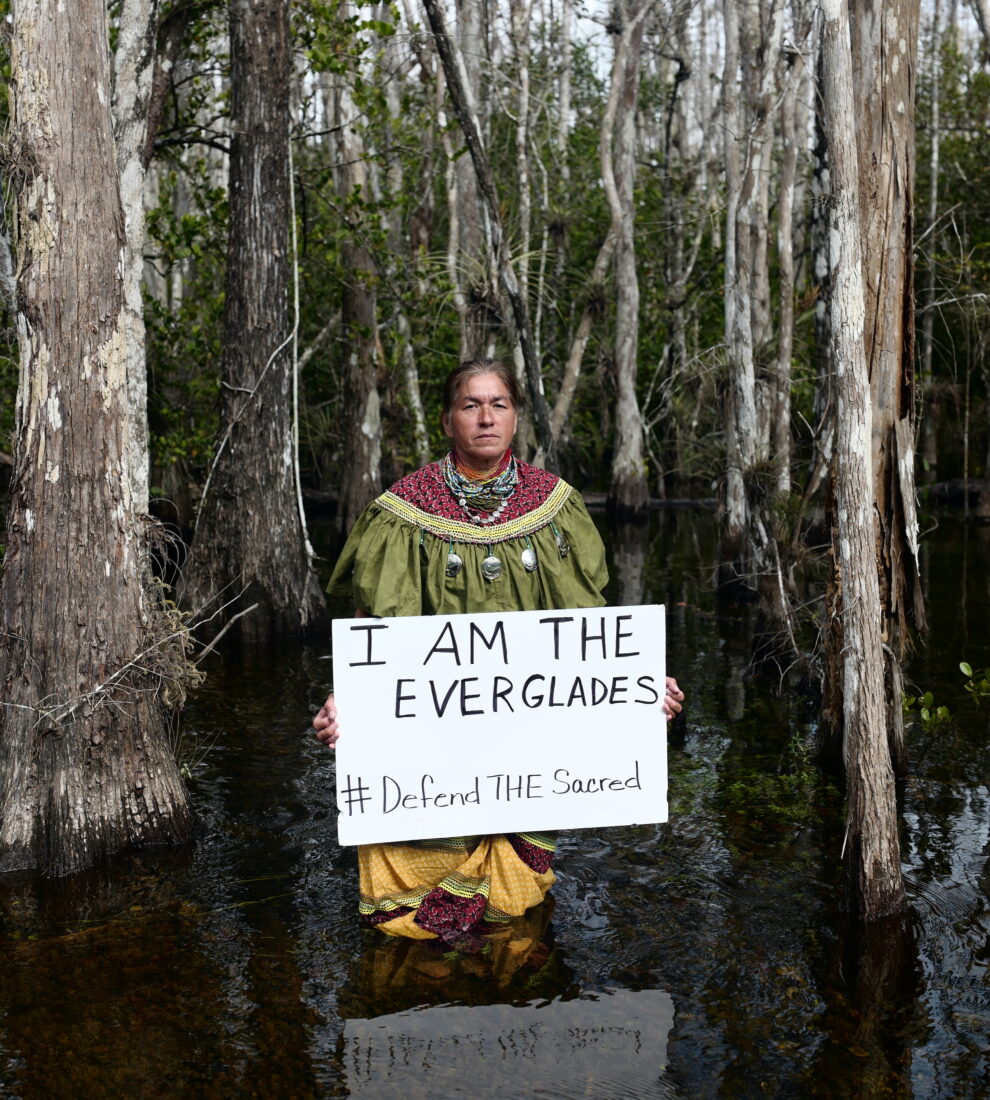

Betty Osceola: Everglades Warrior

The future of her ancestral homeland drives a tribal judge and lifelong environmental activist

Photo: LISETTE MORALES

Betty Osceola in the Florida Everglades, at Big Cypress National Preserve.

Affiliations: Panther Clan of the Miccosukee Tribe; Buffalo Tiger Airboat Tours

Location: Big Cypress National Preserve, Florida

Betty Osceola recalls when subsisting in the Everglades was possible: Her mother and grandmother grew up there in chikee huts on tree islands, growing corn and pumpkins and eating wild game and fish. Osceola herself grew up in a Miccosukee village by the Tamiami Trail, and spent days exploring barefoot, hunting and fishing with her father, and absorbing the ethos of stewardship woven into the Miccosukee way of life.

Today her homeland is beset by threats. The Everglades have shrunk by more than half. Native wildlife is dwindling. Still, much remains to save, and Osceola has dedicated her life to doing just that. More than a decade ago, she took over Buffalo Tiger Airboat Tours along the Tamiami, promising its former owner, the first chairman of the Miccosukee Tribe and a water quality advocate, that she would carry on his work. She now invites guests into the living classroom of the Everglades to raise awareness of the ecosystem’s plight.

Her oversight extends to activism, too: In 2015, she formed the Walk for Mother Earth advocacy group and has led prayer walks across South Florida—notably one along Highway 41 to oppose a seventy-six‐mile bike trail that would have fragmented wetlands, invaded sacred sites, and disrupted biodiversity. In 2019 and 2021, she led 118-mile perimeter prayer walks around Lake Okeechobee to highlight water-quality issues.

In addition to supporting the Florida Wildlife Corridor—a network of protected lands that reconnects the state’s fractured landscape and allows species like the Florida panther to rebound—Osceola serves as a Miccosukee tribal judge and sits on the Everglades Advisory Committee. Recently, she turned her attention to “Alligator Alcatraz,” the ICE detention facility at a small airport in the sensitive wetlands of Big Cypress National Preserve. Osceola speaks at demonstrations and works with other groups to fight it in court.

As she said in her acceptance speech last year when receiving the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Defender of the Everglades award, “We are taught we have to speak for the voiceless. We have to talk for the fish, the trees, the birds, the grass.” —LL

Rashema Ingraham: Island Treasure

A native waterkeeper ensures the tourism mecca of the Bahamas remains unspoiled

Photo: Zach Stovall

Rashema Ingraham with mangrove saplings in the tidal flats off Grand Bahama.

Affiliation: Bonefish & Tarpon Trust

Location: Freeport, Grand Bahama

She grew up on Grand Bahama, and spent summers and holidays in Nassau and Bimini, some of the most stunning landscapes in the Caribbean. But it wasn’t the beauty and splendor of the Bahamas that led Rashema Ingraham to a career spent protecting the well-loved archipelago’s natural resources. It was the stories.

“I grew up playing outside in the wild pine forest, what we called ‘the bush,’” Ingraham says. She spent summers in Bimini with her grandfather Cyril Saunders, a subsistence fisherman and boat-builder whose family members were practically Bimini fishing royalty: His brother was a well-respected fisherman, and his nephew Ansil Saunders was a patriarch of the Bimini bonefishing guide community. “Those experiences connected me to the natural spaces and an appreciation for them,” she continues, “but I didn’t see a larger connection at the time. We thought nature was about attracting visitors. It was a long process to understand that it was something Bahamians should appreciate and protect, as well.”

That they do is in many ways a result of Ingraham’s work. A graduate of what is now known as the University of the Bahamas, she began an eight-year stint with Waterkeepers Bahamas in 2016, ultimately serving as executive director and earning a place on the Waterkeeper Alliance’s list of the top twenty global “Waterkeeper Warriors.” One program under her guidance proved particularly foundational: Faces of the Water provided a platform for fishermen, netmakers, guides, and lodge operators and workers to share their stories about how they were connected to the Bahamian environment. “When I saw the respect their neighbors felt for them as they opened up with their stories,” she explains, “it gave me a deeper drive to build other spaces for Bahamians to share their experiences.”

Now, as the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust’s Caribbean program director, Ingraham has put her expertise in people and policy to work on issues as diverse as man – grove restoration, ecological education, and environmental policy.

The stories of Bahamians undergird all of those efforts. “When it comes to policy development and recommendations for how the fishing industry should move toward the future, guides and everyday Bahamians need to always be in that space,” she says. “BTT is able to provide the larger platform for those connections. It’s like I’m extending the work that my family has been doing for many years and spreading it even farther than I ever imagined.”—T. Edward Nickens

Jody Pagan: Mallard Maestro

Perhaps no one has made Arkansas more duck friendly than this veteran conservationist and biologist

Photo: RETT PEEK

Jody Pagan at Five Oaks Duck Lodge in Humphrey, Arkansas.

Affiliations: Ecosystems Protection Service; Five Oaks Duck Lodge

Location: Searcy, Arkansas

The preservation of duck habitat is no simple matter, as Jody Pagan will be the first to tell you. Luck into catching the longtime Arkansas duck conservationist and biologist during the one hour a month he spends in his office (“I drive for a living”), and he’ll fill your ear with phrases like moist soil management and green-tree reservoir management. Yet when expressed in layman’s terms, the formula that’s brought Pagan success, from his native Arkansas clear down to South America, is pretty simple: “Think about the diversity of products in a Walmart Supercenter—everything from home and garden [products] to milk,” Pagan says. “Just like that puzzle, there are pieces of habitat diversity and habitat structure we have to have to keep those ducks happy all winter long.”

For the past thirty years, in a career neatly trifurcated between government research, private land management, and now entrepreneurship, Pagan has honed that ability to communicate to others the crucial role habitat plays in conservation and hunting. Thankfully, that’s easier than it used to be: “People are smarter now. They’re not doing it like Granddaddy did. They’re doing it like what the science is saying.” But when it comes to courting prospective clients— landowners counted among “the wealthiest folks on the planet”—for his habitat-management company, Ecosystems Protection Service, Pagan says it’s just a matter of getting their eyes on his “showroom”: Five Oaks Duck Lodge.

In 2005, the legendary Ducks Unlimited chairman of the board George H. Dunklin Jr. recruited Pagan to be chief biologist of the equally legendary duck club in Humphrey, Arkansas. Pagan then spent a decade crafting the six-thousand-plus-acre grounds into a veritable waterfowl paradise, using such then-novel strategies as graduated flooding, along with diversifying food sources and places to shelter. Even after he struck out on his own in 2016, eventually working with hundreds of duck clubs and consulting on nearly a million acres of habitat, Five Oaks—his first and longest-standing client—continues to testify to what happens when landowners follow (and keep following) Pagan’s advice. And if they ask him how he knows his methods work? Pagan just shows them the tracking data from the “backpacks” that Five Oaks Ag Research and Education Center has placed on 175-odd ducks— and how they leapfrog to other habitats Pagan has nurtured across more than a thousand miles of Mississippi River alluvial plain.

“See that? See that? See that?” he says, referring to the spreads he’s tended. “That’s a Super Walmart.” —Jordan P. Hickey

Emily Jo Williams: Canopy Keeper

A bridge-building wildlife biologist ensures that working forests work for birds

Photo: GATELY WILLIAMS

Emily Jo Williams surveying at Peters Creek near Georgetown, South Carolina.

Affiliation: American Bird Conservancy

Location: Mount Pleasant, South Carolina

Wherever she might be, Emily Jo Williams’s ears are always tuned for birdsong. “I can’t turn it off,” she says, identifying the buzzy trill of a prairie warbler as she pauses along a forest path near Georgetown, South Carolina, and raises her binoculars to scan a faraway cypress for a swallow-tailed kite nest.

Still, Williams isn’t a typical ornithologist. Over nearly four decades, her stints with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and the Longleaf Alliance shaped a mission far bigger than any one species: Her priority is habitat. Now, as the American Bird Conservancy’s Southeast director of sustainable forest partnerships, Williams knits together habitat in working forests within the ranges of hundreds of resident and migratory bird species.

In other words, “I spend time with people who own and manage forestland—the ones whose decisions influence bird habitat in real time,” Williams says. That includes small landowners all the way up to companies with vast timber holdings, like Resource Management Service (RMS) and International Paper. Williams’s persuasion often works, with owners and companies agreeing to aid birds by, say, leaving dead trees for nesting habitat; maintaining hardwoods like oaks; cultivating a variety of tree ages, a healthy understory, and a buffer of trees around streams; and burning.

Out on this Lowcountry RMS tract, the fruits of Williams’s efforts are on full display. A fifty-acre plot of loblolly pines—carefully managed and regrowing after a harvest five years ago—offers a diverse understory of smilax, blackberry, and sumac. An indigo bunting flits by, and a brilliant red summer tanager alights on a branch; migratory songbirds love young timberlands. A short walk away, an older pine stand dotted with hardwoods gives cover to the likes of wood thrushes and Kentucky warblers, two species of special concern.

Overhead, we spot a bird Williams uses to promote the nonprofit’s mission: a swallow-tailed kite, which South Carolina lists as endangered. Williams trains her spotting scope on a nest harboring a fuzzy white chick, in a string of cypresses RMS left for this purpose. Soon, she will return with other experts to catch kites and attach transmitters that will illuminate their migration to Brazil. “Here is a bird that changes the conversation,” she says as the dramatic raptors wheel overhead. “When a swallow-tailed kite flies across their property, landowners ask: ‘What can I do for that bird?’”—LL

Lori Williams: Amphibious Commando

Fighting to help rare species hold on in the wake of Hurricane Helene

Photo: ANDREW KORNYLAK

Lori Williams snorkels in a French Broad River drainage in North Carolina’s Transylvania County.

Affiliation: North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

Location: Asheville, North Carolina

Lori Williams often can’t believe her luck: She’s a herpetologist who landed a gig in Western North Carolina—the planet’s hot spot for salamander diversity. “It’s like being an artist in Paris,”she says. As the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission’s lead amphibian biologist, Williams oversees the study and conservation of the numerous species inhabiting the region’s nooks and crannies. To name a few: the rock-face-dwelling Hickory Nut Gorge green salamander; the Collinses’ mountain chorus frog; feathery-gilled mudpuppies; the Weller’s salamander, a gold-flecked denizen of high-elevation spruce-fir forests; and the Eastern hellbender, a two-foot-long resident of cold rivers and streams.

To help protect these endemic wonders, Williams conducts population surveys, works with landowners on wildlife-friendly land management practices, and partners with other researchers to design and implement projects with conservation implications, such as a long-term investigation of the effects of prescribed fire on green salamander habitat, and an examination of how far downstream hellbender DNA can be detected. She also has a knack for public outreach, boosting awareness and concern for this hidden biodiversity alongside a handsome costar, her nineteen-year-old hellbender ambassador named Rocky.

After Hurricane Helene devastated the region last September, Williams’s work took on new urgency. “It changed everything,” she says, “and my career will look different for the rest of my time.” Not only did the initial floods and landslides slam amphibian populations already suffering from habitat loss and fragmentation, but such factors as climate change, disease, and the ongoing cleanup efforts are furthering the damage. “The Army Corps of Engineers has machinery running up and down the rivers like highways,” she explains, “with contractors paid by volume to pull out anything and everything—even rocks and live trees, in addition to the legitimate debris that does need to come out.”

Photo: ANDREW KORNYLAK

A subadult hellbender she “goosed” out from under a rock.

Beyond fighting tooth and nail for sustainable clean-up, Williams is reckoning with the hardest hit of the species under her watch. She estimates that last fall’s raging waters affected two-thirds of the hellbender population’s range, and the severe landslides and loss of mature forests most assuredly diminished the number of Hickory Nut Gorge green salamanders, already down to just a few hundred individuals even before the storm. Both will most likely require captive breeding programs to recover—undertakings that loom on the horizon. “We are left with these monumental questions of how to assess what we are left with, and how to begin,” she says. “We are going to have to regain and rebuild.”—LL

Betsey Boughton: Cattle Calling

With a ranch as her ecolab, a biologist proves how cattle operations can nurture ecosystems

Photo: Corey Woosley

Betsey Boughton at Buck Island Ranch with a few of her test subjects.

Affiliation: Archbold Biological Station’s Buck Island Ranch

Location: Lake Placid, Florida

On Buck Island Ranch, 300 bulls and 2,500 cows rotate and graze across 10,500 acres. Sure, this south-central-Florida spread turns out enough beef to put it among the state’s top twenty ranches, but it’s also an ecological laboratory—one revealing crucial insights into how working lands can benefit the environment and remain financially viable for ranchers, thanks to Betsey Boughton, Buck Island’s director of agroecology, and her team.

Historically, prairies and savannas that frequently burned and flooded covered this strip of the Sunshine State, producing an ideal refuge for all manner of birds, insects, reptiles, and amphibians—roseate spoonbills, wood storks, and indigo snakes among them—as well as far-roaming mammals like Florida panthers and black bears. Development has drastically reduced that habitat. “Ranchlands in Florida are some of the last remaining open spaces and systems,” Boughton explains. And working lands compose nearly half of the Florida Wildlife Corridor, a still-growing network of eighteen million acres of key habitat. In Boughton’s view, there’s no reason conservation and agricultural efforts can’t work in tandem: “We can preserve ecosystems at the same time as we’re trying to produce food.”

For the past fifteen years at Buck Island—which is owned by Archbold Biological Station, a long-standing research institution—she has applied her expertise to study that intersection point. For example, she helped implement a program that compensates ranchers for boarding up their drainage ditches to slow the flow of water to Lake Okeechobee, restoring wetlands and lowering the chances of algal blooms downstream. Today nineteen ranch projects participate, with more in line to join. Boughton has also demonstrated that if a ranch divides its grazing areas equally between pastures with native grasses and those with a more nutrient-dense South American grass variety for cattle, it benefits both the cattle and the environment without bothering the bottom line, and that ranchers can implement conservation easements to restore wetlands while still grazing cattle. Plus, Archbold and Buck Island’s data has helped show that, contrary to the oft-repeated premise that all cattle operations contribute to climate change, Buck Is- land Ranch actually absorbs more carbon than it emits.

Best of all, Buck Island’s methods are ready-made for export: The ranch shares all of its data publicly, from profit margins to cow pregnancy rates. And longtime Buck Island manager Gene Lollis, a sixth-generation Floridian, has helped Boughton establish trust with the larger ranching community. “We understand how hard it is to break even in this business,” Boughton says, “and we share the same goals with ranchers. We want to preserve ranchlands for future generations and protect the environment and this way of life. These stewardship values represent the real Florida.”

Dwayne Estes: Prairie Sage

Reviving the South’s imperiled—and nearly forgotten—prairies, meadows, and savannas

Photo: HOLLIS BENNETT

Dwayne Estes at Best Hope Farm in White Bluff, Tennessee, which his Southeastern Grasslands Institute has helped convert back to native grassland.

Affiliation: Southeastern Grasslands Institute

Location: Clarksville, Tennessee

As a child growing up in a difficult home situation in rural Tennessee, Dwayne Estes relied on the outdoors as a place of both refuge and exploration. “My fascination with trees and plants and natural history saved my life,” he says. After dropping out of college twice, he finally clicked with his ecology and evolution studies at the University of Tennessee, an education that solidified his love of botany and, eventually, grasslands.

He quickly realized that a gaping hole existed in the story of Southern landscapes. “It’s the myth of the squirrel,” he explains. “The idea that the forests were so thick a squirrel could travel all the way through the treetops without touching the ground, from the Atlantic to the Mississippi.” But forests never fully blanketed the region, according to historical records; in fact, the landscape consisted of a highly specialized mosaic of forests, woodlands, savannas and other grasslands, and wetlands, much of it open and sun soaked.

While traveling extensively during his PhD research, Estes realized that grassland habitats—an astounding 118 types exist across the Southeast, from prairies to savannas to meadows to coastal dunelands—were little appreciated and fast disappearing. Most of the estimated 120 million acres of original grasslands had turned into cropland or pastures seeded with nonnative species, and fire suppression and development threatened what little remained. Estes had found his calling. A philanthropist gave him start-up money, and in 2017 he founded what’s now known as the Southeastern Grasslands Institute (SGI), a nonprofit focused on restoring grasslands and educating the public about their history and plight. In eight years, Estes has grown that initial $20,000 of seed money into $45 million in grants for mapping and restoration projects all over the region.

Sometimes, SGI has to reconstruct a grassland from scratch. Near Clarksville, Tennessee, Estes and his team mixed dozens of native seeds to revert defunct soybean fields back into prairie. In Alabama, they’re planning to reconstruct the South’s largest prairie preserve, ten thousand acres of so-called Black Belt prairie, full of white prairie clover, compass plant, narrowleaf dragonhead, little bluestem, and gama grass. They’ve also partnered with the National Park Service to enable SGI to improve degraded grasslands and reconstruct others entirely.

Estes is just getting started—he aims for SGI to have directly conserved 250,000 acres, partnered on a million acres, and influenced 2.5 million acres by 2050. “These last grasslands have been hanging on by a thread,” he says. “This wonderful landscape we once had is why the South is so biodiverse, so there’s an urgency to our work that is almost indescribable.”—LL

Tony Mills: Lowcountry Envoy

Preserving coastal diversity becomes an adventure when Tony Mills is leading the class

Photo: GATELY WILLIAMS

Tony Mills catches a juvenile alligator on the edge of a Spring Island marsh.

Affiliations: Spring Island Trust; South Carolina Educational Television

Location: Beaufort, South Carolina

“There’s a lot of similarity between what I did when I was ten and what I do now,” says Tony Mills, grinning as he bounds toward minnow traps he set the previous day in a lush wetland on South Carolina’s Spring Island. Only now, as the Spring Island Trust’s education director, he has this prime piece of real estate as his playground, and his recreation comes with a mission: to reveal and exalt the biodiversity of the South to the public.

More than a third of the sea island, which lies between Beaufort and Hilton Head Island, is protected, and the habitats here, including salt marsh and fresh- water wetlands, shelter a wealth of wildlife. The minnow trap reveals its catch: two crayfish, a predaceous diving beetle, a just-hatched yellow-bellied slider, and a two-foot-long salamander with vestigial limbs so tiny as to be comical, called a two-toed amphiuma. “My favorite thing is to take people out and let them see, catch, or hold an animal in its natural habitat and then release it,” Mills says. “The excitement of the experience is greater when shared—you’re on a collective adventure.”

Though he teaches plenty of classes, including the South Carolina master naturalist course, Mills exports this boundless enthusiasm through Coastal Kingdom, an Emmy Award–winning series on South Carolina Educational Television that he has hosted and coproduced for fifteen years. In each episode, he pursues the likes of coral snakes, red drums, clapper rails, and bonnethead sharks while packing in ecology lessons. Case in point: Mills hops out of his field truck to inspect another trap, this time from a salt marsh, and plucks up the slippery, bulbous body of an oyster toadfish with one hand and the hard shell of a blue crab with the other, all while ex- pounding on how the strange and wonderful bodies of each tell a story of evolution and adaptation.

Over his twenty years at Spring Island, Mills has pursued research and land management as well. He previously honed those scientist chops as a Savannah River Ecology Lab field technician, and today he partners with an ecotoxicologist studying chemical contaminants in alligators. His role is to expertly snag the alligators by the scutes (or scales) with a treble hook and reel them in unharmed. But education is never far from his mind. One of his research projects involves the declining Eastern king snake. On a managed tract of pine forest, Mills is reintroducing baby kings and tracking their performance, and whenever it’s time to let one go, he recruits a member of the public, often a child, to conduct the release. “That person gets to hold this little snake, pick a spot, and send it into the wild,” he says. “When they do that, they feel a connection to the animal and to the land, and that’s powerful.”— LL

Our Trusted Eco-Experts

A distinguished group of panelists weighed in to select this year’s Champions

JJ Apodaca

As executive director of the Amphibian and Reptile Conservancy in Asheville, Apodaca works at the landscape and species level to conserve some of the South’s most endangered animals, including bog turtles, Black Warrior waterdogs, and hellbenders. In 2023, G&G selected the geneticist as a Champion of Conservation, and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service awarded him its Theodore Roosevelt Genius Prize.

Dayne Buddo

Jamaica native and marine scientist Buddo brings decades of expertise in marine policy and protection to his current role as a regional project coordinator at the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism, which encourages the responsible use of the region’s fisheries and other aquatic resources—know-how he cultivated during his previous stints as the Georgia Aquarium’s director of global ocean policy and director of San Francisco’s Bay Academy.

Jimmy Bullock

As senior vice president of forest sustainability at Resource Management Service, a forest investment and management company with a strong stewardship ethos that oversees vast tracts of land across the South, Bullock finds solutions that safeguard biodiversity and critical habitat while keeping working lands working. The 2024 G&G Champion of Conservation’s collaborations with private landowners have aided in protecting such threatened species as the Louisiana black bear and the Red Hills salamander.

Rosemary McIlhenny

A passionate hunter and outdoorswoman, McIlhenny grew up in southern Louisiana on Avery Island, where her family created and still produces Tabasco Brand hot sauces. Over the years, she has been involved in many state and regional outdoor organizations, including serving for a decade on the board of the Land Trust for Tennessee. The Nashville resident is now a newly appointed Tennessee Fish and Wildlife Commissioner and serves on Delta Waterfowl’s board of directors.

Karen Waldrop

In her role as chief conservation officer of Ducks Unlimited, Waldrop leads a four-hundred-strong staff who spearhead wetland and waterfowl conservation efforts across all fifty states. Under her leadership, DU delivered more than a million acres of conservation in a single year for the first time. In 2024, the Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies awarded Waldrop its inaugural lifetime achievement award for her work.