Sporting

Chipping Away at the Old Blocks

Whether you find one or carve it yourself, every wooden decoy holds a little magic

Illustration: Michael Howeler

I’m a duck hunter, stricken early and stricken hard, as a lad of sixteen, cast loose upon the waters of the South Carolina Lowcountry. Gunning ringbills, mallard, wigeon, and woodies mostly, from palmetto-frond blinds in the Combahee marsh or by jumping the black-water ponds behind the barrier-island dunes on Capers, Pritchards, and Fripp. Other duck hunters out there somewhere. In the hush of the high-tide slack wind, in the crystalline frost that comes with it, you could hear the gabble of duck calls and a dog rattle his collar a mile or more away.

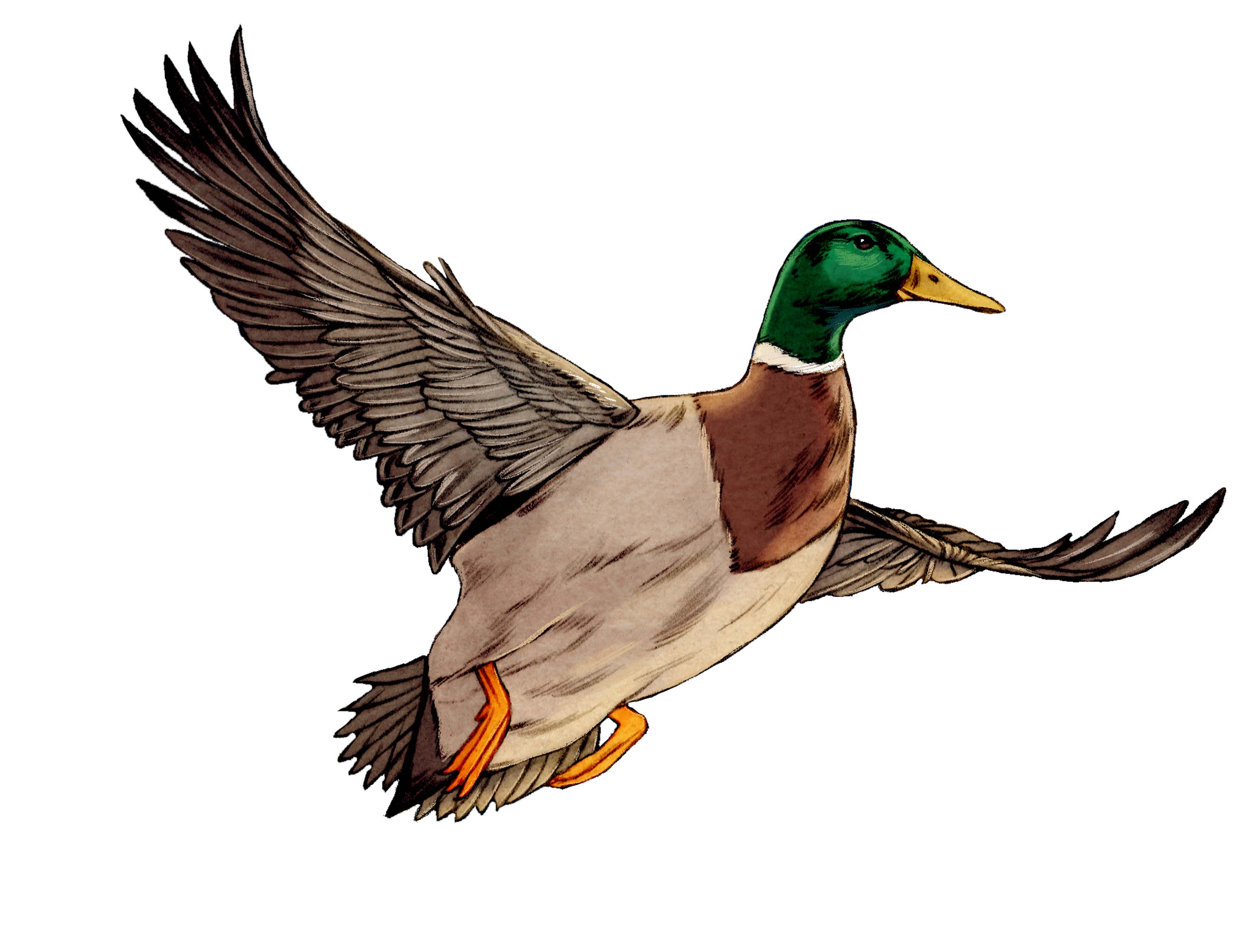

We called the decoys blocks, an easier word when whispering in the predawn can’t-see. They were indeed blocks in duck hunting’s early days, lovingly and artfully carved from cedar, magnolia, or pine, but by the time I came to the gun in the sixties, most of mine were plastic, outside of a few treasured hand-me-down L.L. Bean coastal corks.

Then I ran off to farm in 1973, part of a larger social phenomenon, though I did not know it at the time. But I thought the south end of a northbound horse might do a man some good. And it did. They tell me the same thing happened after WWII, but I was too young then to follow the plow.

Go ye to the field, Ephraim.

Two hundred miles northwest of Minneapolis is where I landed. Longneck returnable beer bottles were two fifty a case, the marijuana grew higher than the corn, and land was a hundred bucks an acre. How much you want? How much can you stand? My initial eighty acres soon grew to three hundred.

Summers were lush and fleeting, wild fruit heavy on bush and vine, gardens bountiful and bursting, cows lowing in the meadow, sweet horses nickering along the pasture fence. Five months later, you could throw a cup of hot coffee into the subzero air and it would never come down, just freeze into a brown fog and drift away on the considerable breeze.

But Lordy, the ducks, October to freeze-up. I have since hunted them from the Río de la Plata to the Zambezi, but never saw ducks like I did on my own land, in my own ponds and sloughs. First came a fusillade at the local mallard, woodies, and teal, then a two-week hiatus before the great flocks of Northern birds blew through on the cusp of the first blizzard. I was shooting a Winchester Model 12 pump in those days, vintage 1957, and I kept it hot. It was sold as “the perfect repeater” and it was, failing me only once, when I force-fed it a Bic lighter in the midst of a furious bluebill shoot.

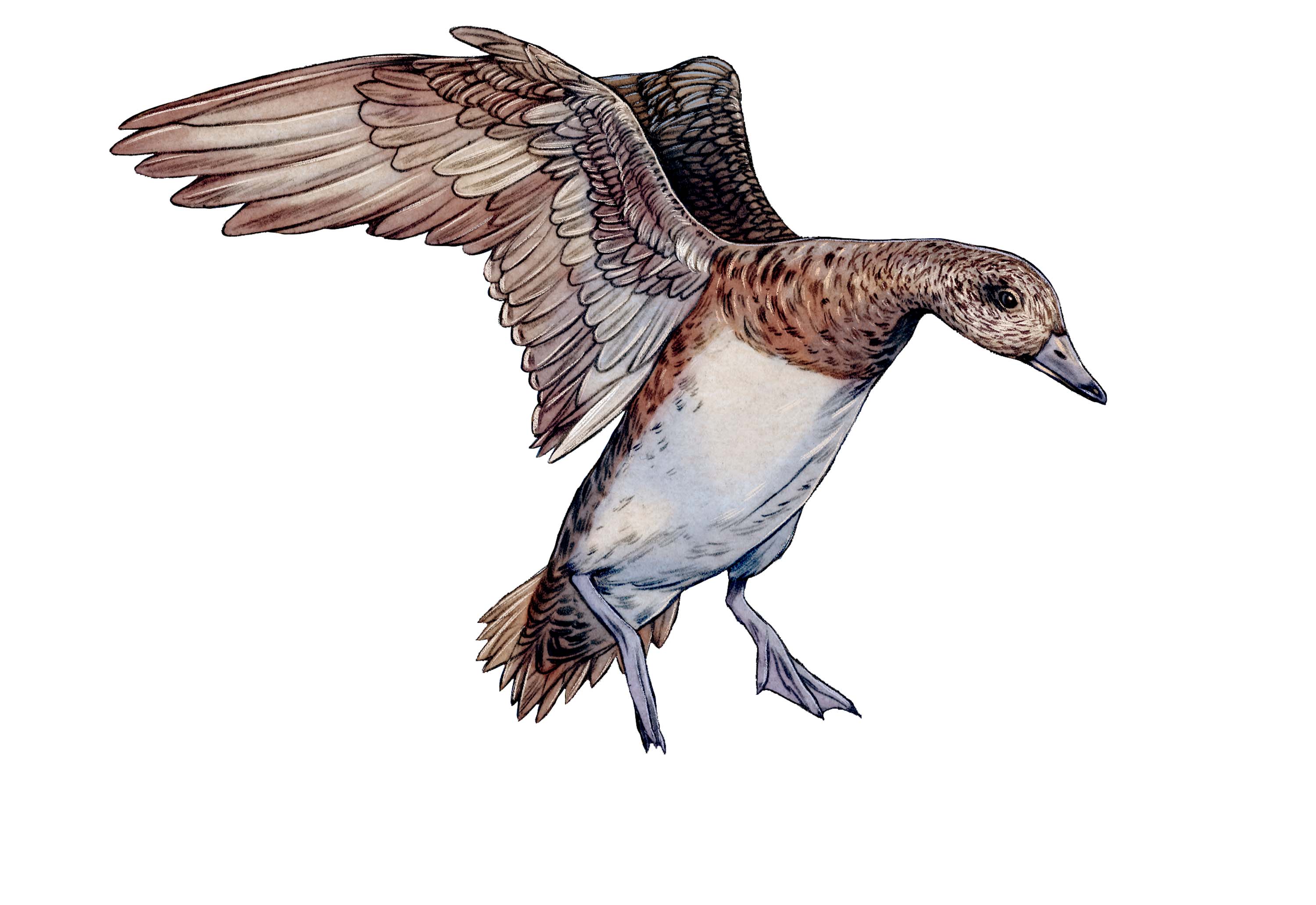

Michael Howeler

But alas, Minnesota was a young man’s game, and snow up to my armpits eventually lost its novelty. In what would be my last winter in those latitudes, 1995, I began to whittle.

It was almost by accident, but there are no accidents.

I was collecting antique wooden decoys, and there were a goodly number of them at local farm auctions. Not only do decoys attract ducks, they attract other decoys. Mantels, end tables, bookshelves, filled with the gathering flock, much to Significant Other’s confusion and growing annoyance. “How come you keep buying old wooden ducks?”

I couldn’t really come up with any logical answer.

One chilly Saturday in a flurry of bidding, I came away with a primitive pioneer teal that bore only a vague resemblance to a real bird. Halfway home, I was struck with a serious case of buyer’s remorse. “I paid fifty bucks for this thing? Hell, I could carve a better one myself!”

And so I did. There was a log-home company just down the road that bought square-cut cedar timbers by the truckload, ran them through a planer that shaped them, and cut tongue and grooves for a windproof seal. Stack ’em like Lincoln Logs with a generous slobbering of caulk in between, drive fourteen-inch spikes with a sledge, chainsaw holes for windows and doors, and you’ve got a house.

Cutoffs and scraps they burned in an oil drum to warm the crew on blustery days—a damn shame, but a man is apt to resort to extremes at ten below. I bummed a dozen chunks the size of shoeboxes.

Just chip away everything that don’t look like a duck?

Yep, but I had help from a certain Mr. Barber.

Joel Barber was a New York architect who, as the story goes, found a red-breasted merganser decoy in a Long Island boathouse in 1918. Smitten or stricken, Barber advanced the notion that hand-carved wooden decoys were a uniquely American folk-art form. Barber organized what is widely credited as the first decoy show, in Bellport, Long Island, in 1923, and his 1934 book, Wild Fowl Decoys, is a seminal work on

the subject.

The book was not so easy to find, especially way up in God-help-you Minnesota. I managed to track down a used copy, and the UPS man struggled a long way uphill in the snow to bring the stained, dog-eared specimen to my door. I poured him a generous dram of Christian Brothers blackberry brandy, the favored local antifreeze.

But to the book. Therein was extensive commentary, photographs, and most important, templates, based on some of the more outstanding examples in Barber’s own four-hundred-bird collection. Those templates came in right handy. They were laid on a grid of half-inch squares. Put the page on a copy machine, blow it up double size, trace the resulting life-size copy on cardboard, cut it out, lay the cardboard on cedar wood, make another tracing with a carpenter’s pencil, and get to whittling.

My nearest neighbor had a band saw, which I employed for the first rough cuts. A few close nips, but I managed to keep all my fingers. The drawknife came next, a razor horizontal edge with a wood handle on each end that you “draw” to you. It made the chips fly. Next was a pit bull of a rasp I dared not handle without heavy leather gloves. Eyes were glass from a taxidermy supply catalogue, and the paint was artist oil, basic colors squeezed from tubes and mixed with a narrow putty knife on a pane of window glass.

I carved late-season birds—ringbills, canvasbacks, goldeneye whistlers—which I deployed in the traditional fishhook pattern. A bull canvasback or two rolling and bobbing and flashing white got the ducks’ attention, drew them down a long shank of female cans and wary whistlers, and finally to a knot of ringbills right before the blind.

It worked famously, but brothers and sisters, I am here to testify, a long string of cedar decoys, properly weighted and rigged, is heavy as hell. I consoled myself: If I were ever caught out in a blizzard, I could burn them to survive. But it never came to that.

I kept whittling. And I went full-bore retro. I bought a Herb Parsons call, made by, or for, Winchester’s exhibition shooter back in the fifties. I never knew which. I traded my Model 12 for a full-choked long-barreled Fox Sterlingworth 12-gauge double from 1936 and found cases of paper shells to feed it. And why not? Duck hunting is a cantankerously difficult endeavor. Be your equipment ancient or modern, you will get equally cold and wet and muddy, so you might as well adhere to honored traditions. Besides, few things are quite as sweet as gunning over a spread you have carved yourself.

Through all the whittling, painting, and rigging, I must have somehow known I would come back to salt water, for I fastened those blocks with screws of marine-grade brass.

Michael Howeler

North Santee River, near Georgetown, South Carolina, Pole Yard Boat Landing, 6:00 a.m. They cut longleaf pine and bald cypress in the Santee Delta in olden times, hauled the logs ashore to mules and wagons—hence the landing’s name. It was cold then and cold now, blacker than black, pinprick stars the only light, the river singing its ancient sad song as it sought the sea, a dozen miles away. We swung downstream, Santee Slim and Captain Ben and me. Slim was a plantation manager, Ben a retired warden, the law in the Santee Delta for twenty-some years. We had a century of duck-hunting

experience and one hundred pounds of my well-

traveled decoys aboard. Destination: Moreland Plantation, four hundred acres of abandoned rice fields, dikes, and canals restored and managed for waterfowl.

The centerpiece of Moreland was a 150-year-old storm tower, a refuge for field hands if caught out in a blow. It looked like a Minnesota grain bin but was made out of brick, with a conical roof and massive windproof doors secured with heavy hand-forged iron hasps and hinges, and that was our base camp that fine chilly morn. Slim cranked the generator and fired up a coffee maker, and we tarried a few delicious minutes before transferring to a smaller skiff waiting in the rice canal. The little outboard churned and juddered through a thin rind of ice, and it sounded like a blender making margaritas.

Slim left us at the blind, went to attend to other hunters. Ben and I set the spread, sloshing about, wobbling in chest waders only inches above wet. No room for my fishhook pattern here, just a semicircle around the blind with enough clear water for the pitching birds. The east began to streak up, yellow green at first, then a flush of pink, and you could smell daybreak on the wind when the first ducks rocketed overhead, a racket like incoming artillery, like ripping canvas—ringbills. They decoy well and taste better.

It was still too dark to shoot, and we knew not what daylight would bring, but I knew this much. I knew we were finally home.

Me and those blocks.

Michael Howeler