Land & Conservation

David Joy’s Unexpected French Connection

On his book tour overseas, the North Carolina novelist discovers that catfish are the ties that bind

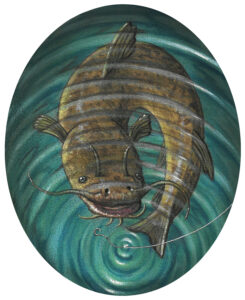

Illustration: Marc Burckhardt

Fig. 1 — Silurus glanis, a.k.a. wels catfish

Matthieu Ravari stands on the train station platform in Albi with a cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth and my name scribbled on a scrap of torn paper. I raise my hand and he half smiles, welcoming me in broken English.

Darkly tanned and tired eyed, he leads my translator and me to a beat-up SUV, where he shovels tackle and trash out of the seats to make room for us. Bait buckets rest on the floorboards. Open maps and food wrappers are strewn across the dash. I’ve been in France on book tour for nearly two weeks, and this is the first familiar sight I’ve seen.

My translator and I had caught the train from Bordeaux at 4:00 a.m. and still did not reach Albi until midmorning. We were late, but it was the only window we had, one free day before I was due at a book festival in Toulouse.

The Tarn River runs 236 miles from its headwaters near Mont Lozère to where it empties into the Garonne below Moissac. The river is known for the wels, a species of catfish that in pictures seems half leviathan. While its large mouth and color resemble those of the flatheads I’d caught all my life, fish that average twenty to thirty pounds and rarely break eighty, its mottled brown body shifts behind the gill plate, tapering long and eel-like. The record on rod and reel measured just over eight feet and weighed nearly three hundred pounds. Just last May an angler in Italy caught a wels more than nine feet in length that most likely would’ve topped the record had it been officially weighed.

After a short ride from town, we launch a center-console skiff from Matthieu’s house and head downriver. Wood pigeons pitch and light on stone bridges as we pass beneath, and I soak in a landscape of tan clay banks and stucco houses, small villages with small churches and large cemeteries. We set up downstream of a bridge where the piers break current into bells of slack water.

The current break is a classic setup, but Matthieu’s style of fishing is unfamiliar to me. There is no casting involved. The technique leans heavy on electronics, spotting fish with sonar and dropping a bait on their nose. It’s a vertical presentation of large plastic swimbaits and small live carp.

Matthieu explains that this late in the morning, most of the fish are sluggish and tight to the bottom. He uses a long-handled tool called a clonk to roust them, each stroke against the water creating a bubble of air that sounds like a cork popping from a bottle. He does this in sequences of three and five, hollow sounds echoing against the cut banks.

“Fish,” Matthieu says.

I glance over his shoulder and see the mark rising on the graph.

“Two meters,” he says.

“Down?” I ask, assuming he means depth in the water column.

“Length,” he says.

My eyes stretch wide. I try to follow his instruction but struggle to place my bait in front of the fish. I can see both the target and the bait on the screen, but it feels like I’m playing a video game. Just as quick as the fish rises, it descends into the bottom. I can sense Matthieu’s disappointment, but he does not voice it.

“Don’t worry,” he says. “We’ll find something bigger.”

There’s a picture of me at maybe four years old standing in the driveway of the house where I grew up in North Carolina. A mess of catfish bends me sideways. I’m wearing a pair of grass-stained tennis shoes and blue jean shorts, a bright green T-shirt, and a ball cap pulled down over my ears. The weight of the fish is balanced on one shoulder, but the struggle to keep them there is evident on my face. I’m about to tip over. Channel cats run the stringer from my chin to my feet.

Every person on my father’s side of the family has a similar photo. They’re always three or four years old. Typically, like me, they’re holding catfish, though sometimes it’s bream and in the case of my uncle and father, a carp. For the most part, all of the fish are from the same river.

For me, place is not simply a matter of land. Place is the intersection of a landscape and a people, two things melded together in such a way that one seemingly cannot exist without the other. I’m a twelfth-generation North Carolinian. My earliest known forebear to arrive in the state came from Virginia in the late 1600s, and by the time of the Revolutionary War, the majority of my ancestors had settled in the foothills along the Catawba River.

My grandmother told stories of catching cats on cane poles when she was a child in the 1920s. My father remembers jug fishing for channels at night in a worn-out boat as a boy, once having to paddle upriver with his father passed out drunk in the back after the motor blew a mile or so from camp. My earliest memory fishing is on a bank in a cove not far upriver from the places they described.

I might be six years old. My father and I are using night crawlers on Carolina rigs, our spinning rods balanced in the forks of sticks cut and jabbed into the clay. A dozen or so other fishermen line the bank. An older Black man with salt-and-pepper hair has a brass bell clipped onto his rod as a bite alarm. After each cast, he slumps in his woven-ribbon folding chair and tilts his trucker hat forward till the brim shades his eyes, and like a magic trick, the bell rings. The other men cuss him, and he laughs. He has a stringer of fiddler cats, small channels sized perfect for frying whole, that stretches the length of his leg.

That is the place I come from, and the catfish are as much a part of it as the river and the people.

Around 12 percent of fish species on earth are catfish. With over three thousand known species, these fishes make up more than 6 percent of all vertebrates on the planet. As the ecologist Archie Carr wrote in 1941, “Any damned fool knows a catfish.” Gilded, firewood, redtails, flatwhiskered, sharptooths, bullheads, Mekongs, Amurs. Pick a country, pick a river, anywhere on earth, and more often than not there are catfish and people who catch them.

The hours before and after sunset are my favorite window of time. Thermals drop, the wind dies, and as this happens, the water stills and quiets. Light dims, and the flatheads begin to cruise. At a lakeside cabin in the North Carolina Piedmont, I often sleep on a pontoon boat with rods in free spool and bait clickers set so I will hear the line ticking off the reel.

Most times, I can tell the species of fish by the way it takes line. A channel cat or gar will strip a reel like it’s yanking the pull cord on a chain saw. Most times it’ll drop the bait. Sometimes it’ll circle back. A big flathead, though, is another fish altogether. It makes its way around a nighttime mudflat like a fat man eating hors d’oeuvres at a dinner party. Casually. The reel goes off, and it does not scream. Just a steady tick…tick…tick like he’s in no hurry at all.

Illustration: Marc Burckhardt

Fig. 2 — Pylodictis olivaris, a.k.a. flathead catfish

The night is full black when the rod goes off and the sound wakes me from a shallow sleep. My heart races and I kick over a pyramid of beer cans trying to get to my feet. The boat is tied to the cabin’s floating dock, and the rods are secured in holders fastened to the dock’s railings. When I reach the rod, I turn off the clicker and lightly thumb the spool to feel that the fish is still taking line. It is there, and so I lower the rod tip to the water, engage the reel, pause for a split second while it takes the last bit of slack, then set the hook hard.

When the flathead is finally near the dock, I struggle to hold the rod with one hand and gather the net with the other. The headlamp shines a dull, dim circle on the water. For a few minutes, it’s a waiting game while the fish wears itself out. Finally, it drives toward the bottom one last time, then rises to the surface like a log.

Its mottled yellow-brown body shines in the light. While most flatheads are beat up and bruised from lives spent wallowing in rock holes and snags, this fish is surprisingly clean. In hand, it is more than forty inches long and weighs nearly thirty-six pounds.

I work the Kahle hook free and marvel at the size of its head, the mouth as wide as a pie pan. No matter how many of these fish I’ve held, I’m always amazed. I grab ahold of its lower jaw with both hands, carry the fish back to water, and ease it below the surface. When I turn it loose, there is no frantic thrashing or panic. The flathead simply slips into the darkness and is gone.

Four years after that first trip down the Tarn, I’m back in Albi at Matthieu’s house. My girlfriend, Ashley, is with me this trip, and she sits beside me at the dining room table. We’re eating cold pizza and foie gras from a can. One of Matthieu’s friends, Yan, has come for the weekend to camp in the yard and fish, and unlike Matthieu, Yan doesn’t speak a word of English.

We’re taking turns drawing catfish rigs on a piece of paper. I show them the Santee rig I use to target flatheads, a twist on a Carolina rig involving a no-roll sinker and a slip float pegged between the swivel and hook to lift the bait off the bottom. Yan asks a question and Matthieu responds. My French is limited to thank-yous and menus, so I hand them my phone and use the translation app to figure out what they’re saying.

I’ve been on the road for a little over a week on a book tour and have to head to Lyon the following afternoon. It’s getting late, and French law prohibits targeting wels catfish after sunset, so we set a time for the morning, and Ash and I head to bed. Yan is planning to fish for carp most of the night, and Matthieu mentions that catfish are a common bycatch. I tell Matthieu to wake me if Yan catches one. Matthieu translates and Yan nods that he will.

As fast as I’m dreaming, there’s a Frenchman banging on the window, a headlamp running a searchlight against the bedroom wall. I throw on clothes and boots and rush into the backyard. Yan’s already dragged the wels into the grass, and it’s lying there stretched out like a month’s groceries. I’m six foot five, and it’s every bit as long as I am.

Yan takes off and races toward his truck to find a tape measure, and when he comes back, we take the length and girth and use those measurements and an equation to calculate an approximate weight. The fish inches close to a hundred pounds.

I grab its bottom jaw and drag it over to one of the backyard lights for a better look. Its skin is the same yellow brown as the flatheads back home, the mouth just as wide, but its head is built much thicker. This is the fish I’ve wanted to see for years, the fish I’ve watched snatch pigeons from sidewalks on television shows and in YouTube videos. I lift the front half into my arms, and Yan takes the back. Ashley shoots a couple of pictures, and we release it back into the Tarn, its long tail fanning and waving a four-foot ribbon.

There’s not a word understood between us, but Yan and I are slapping hands and celebrating and hugging as if we’ve known each other forever. In the picture, we look like brothers—tall and lean, the same long faces, noses, and beards. Sometimes blood is nothing more than a fish, a river, and a people. Sometimes I think I could’ve been born anywhere on earth and turned out exactly as I am.