Travel

In Praise of the Southern Road Trip

As summer beckons, six writers chase the open highway, dropping pins along the way at a Mississippi barbecue joint, backlit Blue Ridge vistas, and a cerveza-soaked border town that practically wrote itself into the ultimate road trip song

Photo: Gately Williams

Cape San Blas Road bends toward the Gulf of Mexico near Port St. Joe, Florida.

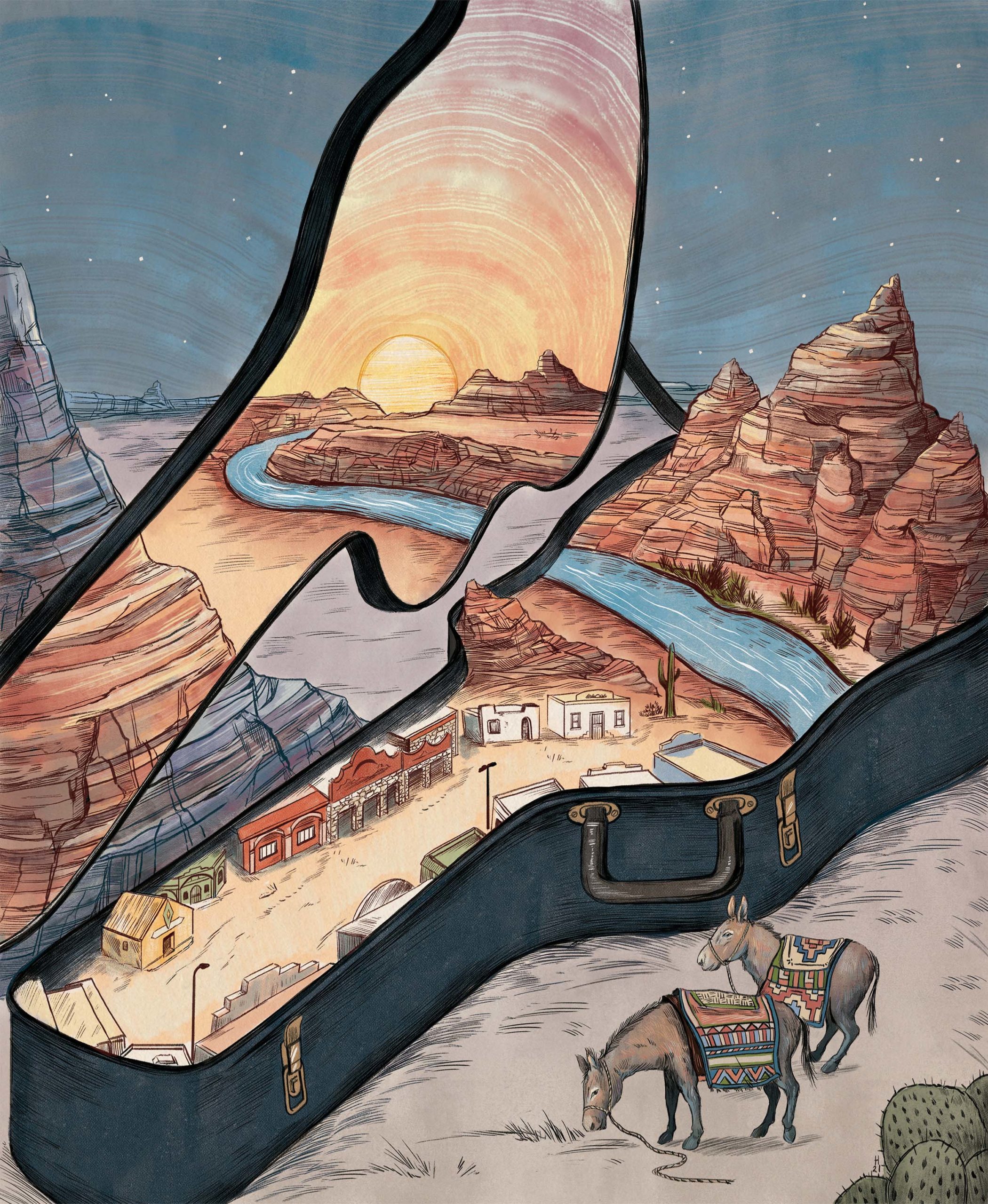

LYRICAL REWIND

Gringo Honeymoon

How an off-road adventure inspired the classic Texas song

By Robert Earl Keen

Derik Hobbs

Ralph Waldo Emerson never met the Slim Duck. He never met Gray Dude or Ginger. And he certainly never crossed the great American West in a ’67 Barracuda convertible. But had RWE experienced anything akin to making a road trip with a bewitching heartthrob like the Slim Duck, he might have tempered his opinion about traveling being a “fool’s paradise.”

If traveling is a fool’s paradise, then hand me those sunglasses and pass the beer. I’ve been a fool for traveling since the last quarter of the twentieth century began, and I made my virgin road trip to Los Angeles with the Slim Duck, her black Lab, Ginger, and her surly African gray parrot, Gray Dude. This was my first adventure born of reckless abandon. The Duck, a ravishing and fearless freedom fighter, threw her compass to the wind and put her barefoot fun locator to the accelerator. Along the way, we experienced everything from breakdowns to break-ins; from sleeping in the car to cantina bar fights to camping under the desert night sky with a zillion stars. Our L.A.-or-bust interstate expedition gave birth to a lifetime of wanderlust. Moreover, our junket gave me my first glimpse of the vast Far West Texas land known as the Trans-Pecos.

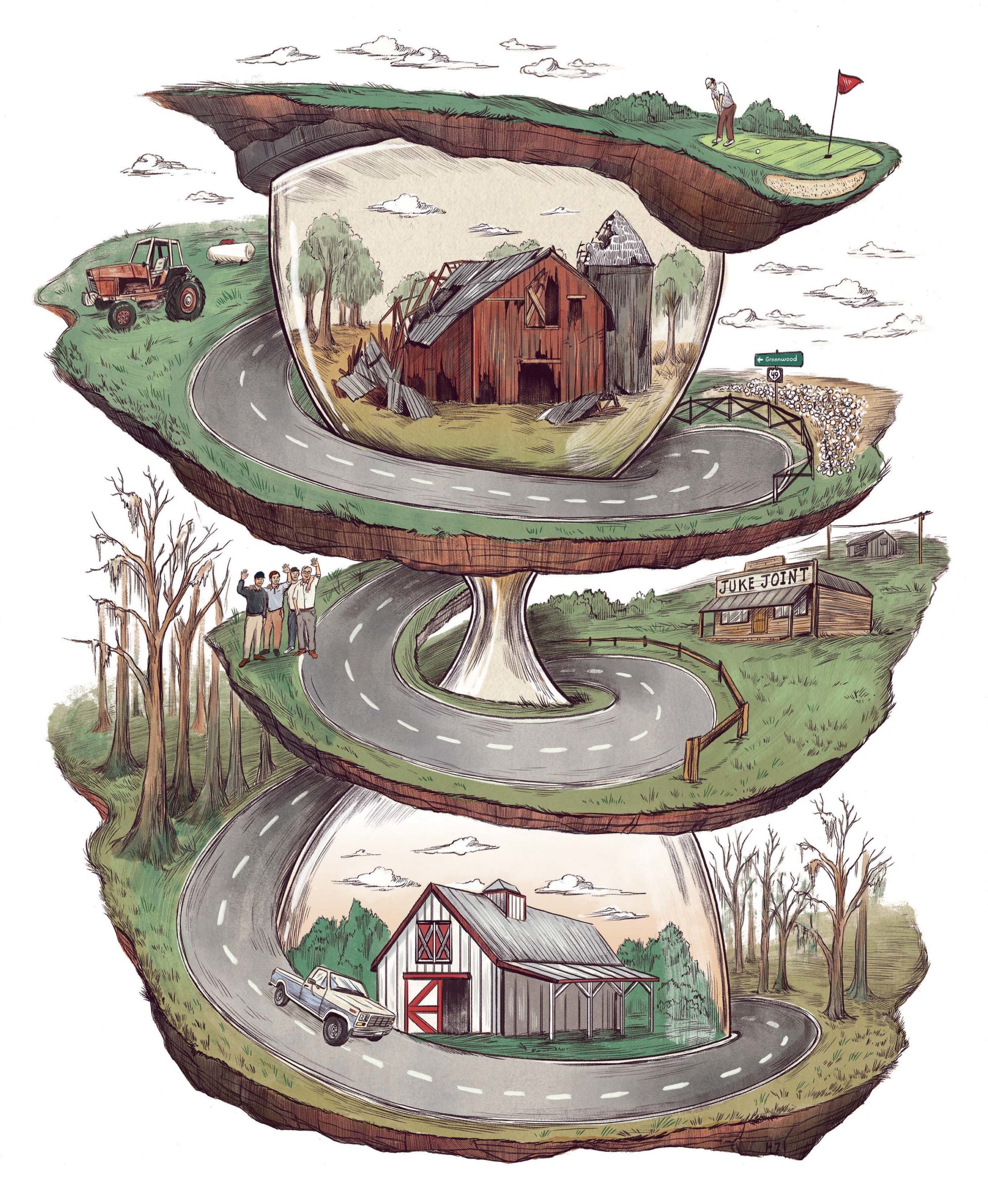

RETURN TRIP

Riding Shotgun

Journeys into the heart of Mississippi

By Jessica B. Harris

Photo: Evan Sung

Pulled pork sandwiches with cole slaw at Betty Davis Bar-B-Que.

I am not a driver. As one who has spent her entire adult life in New York City, I have never needed to know how to operate several tons of metal on an asphalt track. Now, however, after more than a year of sequester and confinement, I find myself wishing that long, long ago I had mastered the rules of the road. I muse back on good times spent riding shotgun or simply rolling along in the back seat without a worry about navigation or speed limits, with my eyes free to view the countryside and the roadside attractions.

As my mind goes over the multiple road trips I have taken, one keeps pushing itself to the top of the list. That trip runs from the Memphis airport to Oxford, Mississippi, and then rambles farther into the state to Greenville. I was an annual regular on those Mississippi roads for ten years in the 1990s and then again for another five in the late 2010s.

My initial ride on the Oxford section of the journey was my first trip into the reaches of the Deep South. For me, a Northern-born Black person who had no Southern relatives, Mississippi was a place of memory and fear from flickering television sets of my youth; it was the fabled South, the South of racial memory and unspeakable history. Simply the word Mississippi was daunting. What would the road hold?

MAPPING THE PAST

Parkway Intersections

The Blue Ridge roads that raised me

By Ron Rash

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

A view of the Appalachian Mountains along the Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina.

A few miles west of Blowing Rock, North Carolina, near milepost 297 on the Blue Ridge Parkway, is Price Lake. In 1972, my cousin Mike and I fished here. He was just back from Vietnam. We fished until dark, little disappointed at our having no luck. His being home safe was all the luck we needed. Drive north a few miles and you’ll cross over a stone bridge built by the WPA during the 1930s. The stream that passes underneath is Middlefork Creek, where once I caught a rainbow trout big enough to warrant a paragraph in the Watauga Democrat. Another half mile down on the right is a road that leads to where my aunt Lee and uncle Roy lived. Besides their growing the best corn I’ve ever eaten, Aunt Lee tended an immense flower garden. One of my earliest memories is of watching butterflies brighten the mountain air above it.

Farther along, you’ll come to a pull-off on the right for Thunder Hill Overlook. In daylight the view is marvelous, a blue expanse that appears as endless as the sea. If you come at night to this area, you might look out and see the Brown Mountain Lights. Scientists have theorized that their source is fox fire or automobiles. However, local lore holds that the roving lights are lanterns carried by restless spirits. In their adolescence, my uncles and aunts came here with their dates, but I suspect their focus was not on otherworldly matters.

In another mile, if you look closely on the right, you might glimpse some graying locust posts linked by sagging strands of rusty barbed wire. My grandfather built that fence in the 1930s when he decided to raise cattle. In that pasture is a hill atop which, sixty years ago, you might have seen my cousins and me. We would be looking in your direction, playing a game where we guessed the next car tag’s color. Sometimes we’d venture closer to the parkway to identify the states: yellow could be Maine or Michigan, white Idaho or Kentucky, and the rarest color of all, the bright red of New Mexico. How strange it was as a child to know that people from so many places passed so close to our lives.

MANATEES OR BUST

Coasting the Gulf

A lollygagger’s ideal itinerary

By Pam Houston

Photo: Jeff Greenough

Oysters on the half shell.

A perfect road trip begins at happy hour, at Superior Seafood and Oyster Bar on St. Charles Avenue in New Orleans, for a dozen (or maybe two) oysters on the half shell and a frozen French 75. I know frozen drinks are for teenagers, and I am not one, but that combination of gin, champagne, and lemon juice makes its own special mignonette that forms a lazy river from my mouth to my belly, and since that is what I had the first time I went to Superior almost a decade ago, it is hard to imagine one without the other.

Arrive early and sit at the bar. Oysters are fresh, cold, plentiful, and seventy-five cents apiece at happy hour, shucked by oyster whisperer Kelly Keefe (one of the few female shuckers in town). Superior has three of the top-ranked shuckers in the state, and not only are they fast, they treat everybody like family. You may wind up with Chauncey Gardner-Johnson’s mother on one side of you and George Porter Jr. on the other. And if George Porter Jr. invites you to hear his band at the Maple Leaf Bar, go!

TOWARD HOME

Memory Highway

Driving with my eyes closed

By Wright Thompson

Derik Hobbs

If the priests were correct for once and I were to ever go blind, if my world went to shadow and black and I couldn’t see a solitary thing, I submit for your consideration that I could still drive from Yazoo City to Greenwood, Mississippi. I know this journey cold. Surely you’ve got a road like that. A drive you can make without thinking, each turn and straight carefully wrapped and stored in the closets of your memory. I’ve ridden this road hundreds of times. The first was when I was just weeks old. The last time was a week ago.

The first left took me down a wooded hill away from my uncle Will’s house, where he lay in a bed dying. His room overlooked those same woods. I’d come here to say goodbye and in his familiar house, where we’d gathered so many times, I couldn’t shake the strangeness of his shrinking world.

THE SLOW LANE

Rides of Passage

Saluting the spirits of Old Florida

By Taylor Brown

Photo: Cedric Angeles

Deep in Louisiana’s Atchafalaya Swamp.

We cross the Florida line at noon, thundering through forests of spindly back-road pines. Tar snakes slither before us, gluing the road together in kinks. We’ve been circling Georgia’s Okefenokee Swamp—the most primeval of Southern wilds, which survived the drainage attempts of former Confederate officers and the ravages of forest fires said to rain ash and smoldering moss on towns downwind.

It’s 1999. Spring. I’m sixteen years old. My father and I are riding our motorcycles in echelon, our boots kicked out on the pegs. We’re on the way to my grandmother’s house, around the swamp and across the Panhandle, to Fort Walton Beach.

My father loves to strike out riding for the coasts of Florida where he grew up. He follows serpentine byways and dead-straight alligator alleys, finding his way to little-known fishing villages, the last bastions of Old Florida where shrimp boats sit on blocks and canned beers slide across plywood bars and people watch the sun crash into the Gulf of Mexico. During his lifetime, these villages will give way at a dizzying clip to high-rise condominiums and golf carts; he’ll be forced to look ever harder for the Florida he once knew.