Home & Garden

Joseph Hillenmeyer’s Green Kentucky Home

How the boundary-pushing garden designer, born into a generations-long legacy of accomplished plantsmen, discovered his own remarkable path

Photo: Anya Lorenzo

A garden Joseph Hillenmeyer designed peers through to horse pasture in Midway, Kentucky.

One day when Joseph Hillenmeyer was a teenager, a football player challenged him to a pull-up contest.

Both of them were enrolled at McCallie, a respected Tennessee boys’ school that counts among its graduates Ted Turner, the Pulitzer-winning author Jon Meacham, and a smattering of congressmen. Joseph agreed, though his challenger, beefy and confident, outweighed him by seventy pounds or better. Grabbing the bar first, the football player managed to huff his way to thirteen pull-ups before stopping. Taking his turn, Joseph—slim, but also an avid rock climber who slipped off campus most afternoons to test his mettle on the bluffs around Chattanooga—began methodically pumping out reps, and quickly surpassed his rival’s total. At thirty pull-ups, he paused for effect, holding his chin above the bar, and crowed, “Do you want me to keep going?” Soon his chastened competitor left the room. When Joseph reached sixty-two reps—establishing a school record that held for years—he stopped.

If this seems to have little connection to his current profession as a designer of striking home gardens, it does at least suggest one area of overlap: Joseph Hillenmeyer isn’t shy about going big.

Nearly three decades after that moment of adolescent glory, determination and persistence are still serving him well. The scion of a long line of horticulturally minded Hillenmeyers who trace their ancestry back nine generations to the 1700s in France and Germany—six of those generations in Kentucky—he’s now the principal and visionary behind Joseph Hillenmeyer Garden Design. That small firm has a blossoming reputation and millions of dollars’ worth of projects on the ground and on the drawing boards, from his hometown of Lexington to bluff-top estates in Louisville to around the South and beyond. In March, Hillenmeyer and his wife, Shannon, who is also his company’s controller, moved both their home and their business to a ten-acre spread on the outskirts of Lexington, where a gleaming two-story studio overlooks a classic Bluegrass panorama of green and gently sloping horse farms. Largely self-taught, and having never bothered to earn a college degree in horticulture, landscape architecture, or any other subject, Hillenmeyer (who’s now forty-four) has gradually carved out a niche for himself by drawing on a fascination with plants, heartfelt reverence for his family’s Kentucky legacy, and boldness born in part, he admits, out of naivete. When he began dreaming up landscapes for clients, he says, “I pitched big ideas because I didn’t know I shouldn’t.”

Photo: Alison Gootee

Hillenmeyer in his studio on the outskirts of Lexington.

On a balmy spring afternoon, Hillenmeyer is giving me a bit of a crash course in those big ideas, or at least a few ABCs of how he tweaks and manipulates the scenery around a home—setting a stage for whatever might unfold at the junctures where humans’ and plants’ habitats converge. We’re taking a counterclockwise stroll through one of his pet projects, the manicured grounds around a white-brick-and-clapboard house in the town of Midway, a short ride from Lexington along Thoroughbred pastures lined by stacked-limestone fences. The owner of the home is Dottie Cordray, a cousin of Hillenmeyer’s father’s who entrusted Joseph with her garden nearly two decades ago, when he was young and unproven, and he’s embellished and added to it in phases ever since. “There were a ton of other family ties with way more experience,” he says, his tugged-up shirtsleeves revealing brightly tattooed forearms. “But she took a huge risk and tapped me for the work. She’s also given me the freedom to not have a fully developed plan.” The metaphor is as subtle as a Hollywood asteroid but seems unavoidable: He and this miniature Eden have come into their own together.

The garden sits on a lot of no more than an acre on a tidy residential street, but it feels both more expansive and more isolated, and that’s no coincidence. Nine Japanese maples, a lacy cultivar called Seiryu, flank a shaded masonry courtyard along the driveway. “When those leaf out, that house”—Hillenmeyer gestures toward the one next door looming over a wooden fence—“disappears.” That’s not the only botanical Photoshopping going on: On the other side of Cordray’s house, a “borrowed” view of a neighboring horse farm over a low yew-and-boxwood border stretches to the horizon, making it easy to imagine you’re standing at the center of an estate that sprawls for miles. But there’s a twist: Hillenmeyer intentionally obstructed much of that “moving art,” as he describes it, with a taller hedge of hornbeam trees and hydrangeas, measuring out the million-dollar view beyond only in glimpses. “I feel like it’s more appreciated when it’s revealed slowly,” he says. “I’m creating a frame for a picture.”

A look in any direction reveals more painstakingly plotted details. Espaliered Kieffer pear branches that he trained early on to hug one side of the house blur the boundary between home and garden. Bluestone paths accented with three-deep bands of limestone edging and boxwoods rounded into evergreen orbs lead around corners, nudging a visitor to keep moving to discover whatever “moments of surprise” (Hillenmeyer’s words) await just out of sight; other, more intimate spaces, like a sycamore-shaded “sunset garden,” beckon you to plop down on a bench with a glass of wine and linger awhile. Colors and textures echo and repeat. It’s like a visual symphony in which the same snippets of melody show up time and time again, but with slight variations in tempo and pitch and volume: Rhapsody in Green. “A garden,” he says as we complete our lap around the property, “is the most ephemeral art there is.”

* * *

Photo: Anya Lorenzo

A path through the Midway garden.

“I’m not a religious person,” Hillenmeyer tells me later that afternoon, “but I am a spiritual person, and this to me is holy ground.” We’re standing in the upper level of a hulking brick warehouse on Lexington’s perimeter, gazing up at sky-lit rafters. To the naked eye, the building appears largely empty, but in a sense it holds a mother lode of both Kentucky and Hillenmeyer family history. The place even smells like history, a dusty, slightly damp aroma with a hint of ancient cider mill. “It’s a nursery business,” Hillenmeyer explains. “What you’re smelling is burlap.” Added onto over generations, the space was built as a cotton mill in the early 1800s by a Colonel Sanders (no, not that one). In time it passed on to the Todd family, during whose tenure that Kentucky native Abraham Lincoln visited the adjoining office of Robert Smith Todd, his eventual father-in-law. As befits a cavernous storehouse in Kentucky, it then became a distillery rickhouse, stacked high with barrels of aging Old Elk bourbon. In 1915 it changed hands again, soon to become the beating heart of Hillenmeyer Nurseries.

Three generations of Hillenmeyers worked out of this site, and to Joseph and others in his extended family, the nursery grounds embodied a sort of noble birthright, an inherent connection to the land and to hard work, not just a prosperous business—although it certainly was that. Founded by a forebear who made his way to then-frontier Kentucky from the Alsace region of France in the 1840s, the nursery partnered during the Great Depression with Sears, Roebuck and Co., at the time the Goliath of American retail, fortifying a horticultural empire that at its peak cultivated hundreds of acres of growing grounds and shipped bare-root fruit trees and rosebushes all over America. Joseph’s father, Louis, who’s now in his seventies, literally grew up at the nursery. As children, he and his brothers played hide-and-seek in the warehouse’s cellar, and he recalls workers back then wrapping burlap around their waists, like long skirts, to stay dry while walking the fields behind mule-drawn plows. At his design studio, about ten miles from the old warehouse, Joseph keeps a treasure trove of Hillenmeyer Nurseries mementos: yellowed catalogues from the 1930s and ’40s, black-and-white glossies of Louis posing with assorted First Ladies during White House ceremonies. A priceless early-1900s photograph shows the Haymakers, a farm-league baseball team the nursery sponsored, with Joseph’s great-grandfather one of the baby-faced young players posing in front of a stone fence.

Photo: Alison Gootee

The onetime Hillenmeyer Nurseries warehouse.

Born into a bloodline whose members practically emerged from the womb with dirt under their fingernails, Joseph predictably worked odd jobs around the nursery from age seven or eight. Even earlier than that, he tended a vegetable plot of his own and began collecting birds’ nests, feathers, and animal skulls, but he didn’t take a straight path to his eventual vocation. Diagnosed and treated for ADHD from the third grade on, he had high energy and low tolerance for boredom. “If I was interested in the class,” he says of his school days, “I’d get an A. If I wasn’t, I might fail it.” One summer, he amused himself by shinnying up onto the roof of some neighbors, a Japanese family who’d moved to Lexington after Toyota opened a mammoth plant nearby; aiming a universal remote through a skylight to switch TV channels in the room below, Joseph looked on as Mr. Ioku blew a gasket, furious and baffled at the way his television malfunctioned anytime he tried to watch golf.

After graduating from boarding school, where he’d begun climbing mountainsides instead of rooftops, he attended Appalachian State University, in North Carolina, off and on for a total of two years. “I went to App State to climb,” he confesses. “I was bored to death. I was not engaged at all.” He also bounced around in the States and abroad, but even far from home his plantsman DNA tagged along: He worked with a renowned nurseryman named Don Shadow (“my horticulture mentor”) in Tennessee, at a couple of farms in New Zealand, at a private arboretum outside Istanbul. In Turkey, none of his coworkers spoke English, so he spent his free time learning Turkish from children’s books and poring over horticulture volumes in the arboretum’s library. “I learned more in those years overseas by far than I did sitting in those classrooms,” he says. By this time, his father had been bought out of his share of the longtime family nursery (which, along with the historic warehouse, gradually got sold off; sections of the onetime growing grounds have now sprouted subdivisions and a Coca-Cola bottling plant). Joseph circled back to Lexington to help him out with a new garden center, imagining he’d stick around his hometown for a couple of years and then bolt. “That’s when I started doing design work,” he says. He’d sketch out garden plans on a notepad and sell homeowners the plants to go plop in the ground themselves.

Photo: Alison Gootee

A landscape design takes shape.

When something grabs Hillenmeyer, though, it really grabs him, and his fascination with design snowballed. He moved out of his parents’ house into a 1915 bungalow on Richmond Avenue, using what remained of his college fund for a down payment. (When he surprised his parents by announcing that purchase, his father, whom he describes as “a ten-mass-a-week Catholic,” replied, “Who the hell loaned you money?”) Suddenly in possession of a yard, he started building gardens, “not having any idea what I was doing”; he persuaded neighbors to let him landscape their yards as well, for free, giving him a bigger canvas to test out ideas. He ordered specialty plants: Japanese full-moon maples, cultivars of the fragrant perennial Solomon’s seal, shade-loving sacred lilies. “I became fanatical about it, experimenting with anything that I could,” he says. “That’s the beauty of ADD. When you are passionate about something, it gives you the ability to focus much more than most people can. Or should.” He taught himself to draft and pieced together a library that now numbers almost 3,500 volumes. He and a partner formed a landscaping company; after they split, he took bigger leaps of faith, selling off the steady revenue streams of landscape installation and maintenance. The future on which he now focused his autodidact zeal left little room for keeping laborers busy on rainy days and scheduling oil changes for a fleet of trucks.

“I always wanted to do things that meant something,” he says, even when that didn’t come easy. Four or five years ago, after he’d married Shannon, “at one point we were broke. I was getting big jobs; I just wasn’t getting enough of them.” He promised his wife that if his garden designs hadn’t sufficiently taken off by the time he turned forty-two, he would “sell widgets if that’s what I had to do, instead of chasing dreams.”

Around three years ago, though, “something just started to hit.” Word of mouth spread, and prospective clients from Kentucky and elsewhere started calling more often. In the last year, he began hiring staff to help with design and with steering the business. At the moment, thirty-two active projects as far afield as Utah are in the pipeline, with blueprints and renderings pushpinned all around the studio’s white corkboard walls, some of them budgeted at north of $2 million. The widgets, it looks safe to say, are on permanent hold.

Photo: Anya Lorenzo

Espaliered Kieffer pears.

“He’s amazingly creative,” says Leon Hollon, who along with his wife, Sandy, is a longtime client of Hillenmeyer’s (and of his father’s before that). The Hollons live on thirteen mountainside acres in Hazard, an Eastern Kentucky coal town to which Hillenmeyer has a deep-rooted connection; his maternal grandfather practiced medicine there and delivered more than thirteen thousand babies, at times for parents who could not afford to pay. (Hillenmeyer’s eyes well up at the memory of being dandled on Dr. Boggs’s knee while listening to old Cab Calloway records. “He was just a remarkable man,” he says. “When I hear ‘Minnie the Moocher,’ it’s like a time warp.”) The Hollons’ property now includes a koi pond encircled by eighty-five tons of stone from Rockcastle County, a rose garden that looks out onto six or seven mountain ranges, and a redbrick wall built atop a steep drop-off “that gave us a yard,” Sandy says, “which we never had. He’s just got such an eye for detail,” she adds. “Nothing’s impossible.”

* * *

“This was just a lawn before we started.” We’ve stopped by another Hillenmeyer creation, a yard of a half acre or so in a leafy Lexington neighborhood. The onetime sod patch in front now boasts elegant terraces of boxwood and low brick walls, and the backyard contains a number of clever flourishes. Busy street out back? Plant a tall screening of arborvitae fronted by smoke trees to obscure passing cars, and install a rectangular twelve-jet water feature to muffle the noise. Need something for the homeowners’ eyes to rest on when they step outside? “Looking out the back door, you get this sculptural moment,” Hillenmeyer says of a three-tiered, stair-stepped hedge of taxus framing the fountain. “It’s very dramatic.” Another trick: Having reserved a spot for a redbud tree off a corner of the house, he found one from the shadowed edge of a nursery that was already reaching up to one side toward sunlight. Thus, he explains, when transplanted to its partly shaded spot in this garden, it looked as if it had been reaching for light in its new home for years, giving the young landscape a mirage of instant maturity, what he likes to call patina. “I don’t know anyone else who’s done that,” he says.

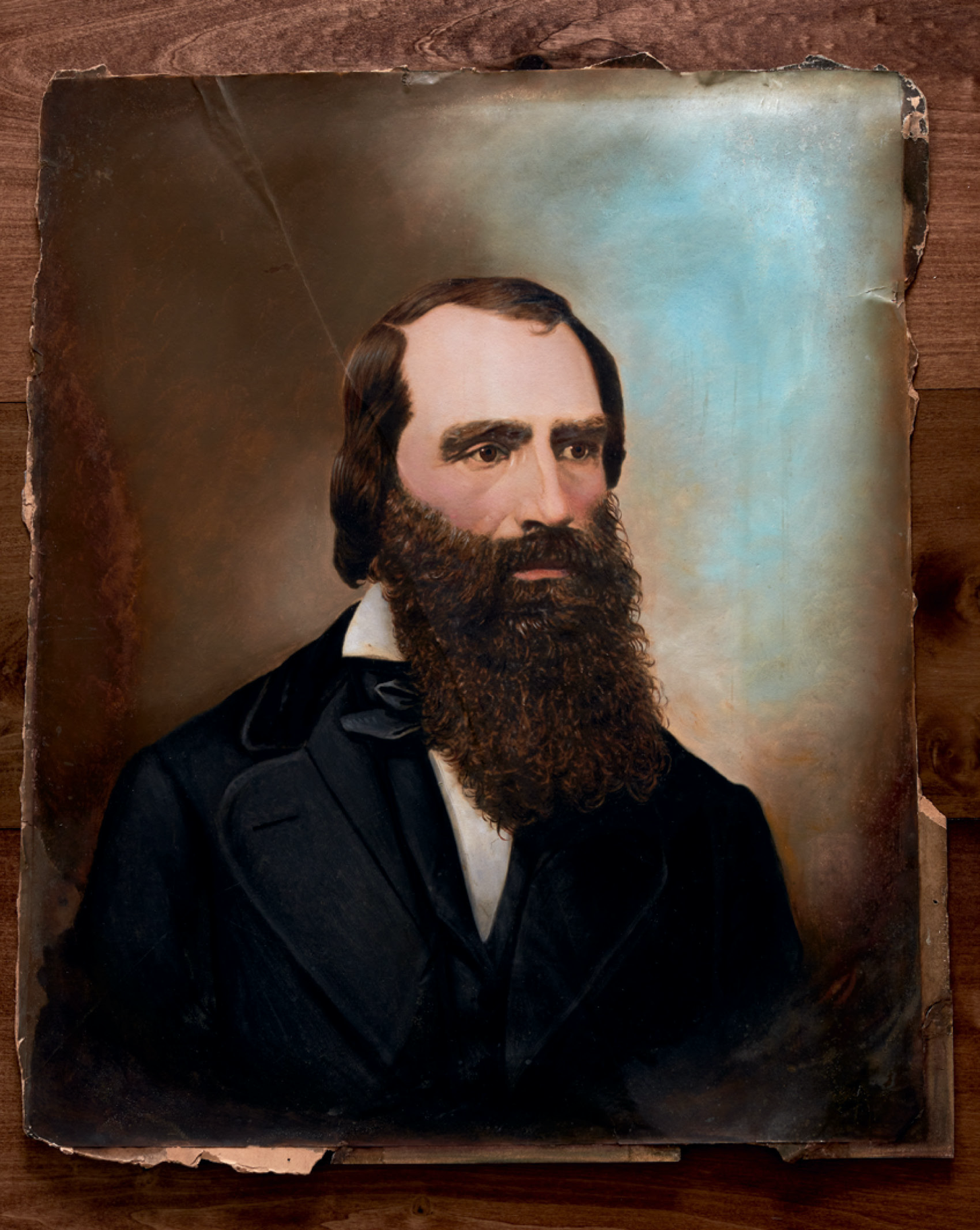

Photo: Alison Goote

Joseph’s ancestor Francis Xavier Hillenmeyer, who arrived in Kentucky in the 1840s.

Those sorts of gutsy, instinctive touches have become Hillenmeyer trademarks, along with a rapport with clients—a “dinner and cocktails approach”—that blends conviviality with a cheerful but almost dictatorial bluntness. “Some designers,” he says back at the studio, “start out with ‘What colors do you like? What’s your favorite day of the year? What’s your sign?’” But when clients “start to tell me too much,” he adds, “I push back at that.” His recent hires have gradually learned not to be alarmed by the unvarnished opinions Hillenmeyer might voice while pitching a project, such as his opening salvo to a Louisville couple, just after meeting them: “You’ve got to get rid of this tennis court.” He’s broken the news to two or three different clients that their swimming pools were badly mislocated. “You look at a pool ninety-eight percent of the time, and you get in it two percent,” he tells me. “It needs to be a water feature that you happen to be able to enter.” After a recent pitch meeting with a homeowner, when Hillenmeyer and Chris Beaulieu, one of his associate designers, got back in the car, Beaulieu stared at him, aghast: “You just told her to rip the front of her house off!” They got the job.

“I’m not scared to throw out a crazy idea,” Hillenmeyer says. “So I go to people with these big strokes—‘I want you to walk out of your house and walk through this serpentine hedge.’ My drive has always been to create things that are different and unexpected. I’m not interested in regurgitating somebody else’s work.”

As we chat, the sun starts to sink low, and we decide to climb into Hillenmeyer’s truck for the minute-long hop to his house, where tall cups of bourbon on ice will soon appear. “I really love pushing boundaries,” he says, just before we exit the studio. “That’s kind of inevitably where it goes.”