Land & Conservation

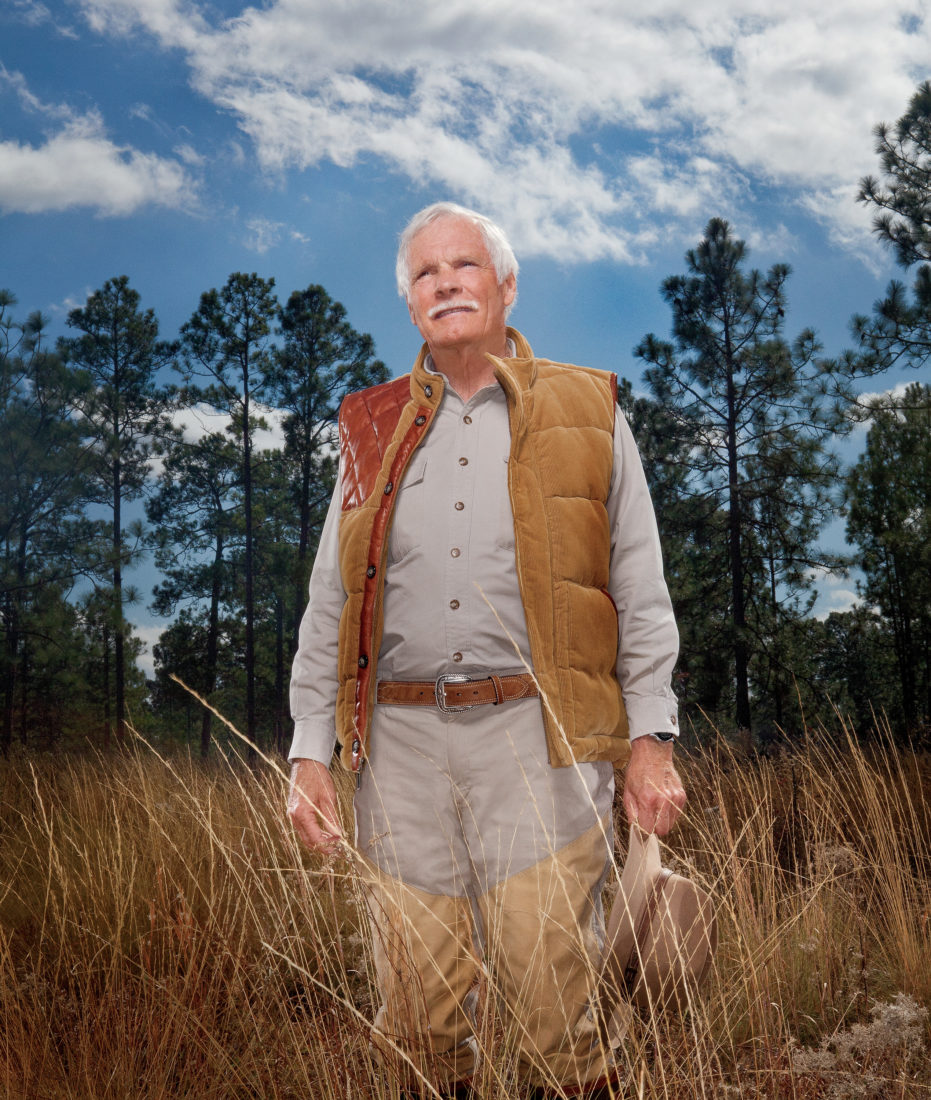

Ted Turner: Going Native

Ted Turner’s latest acquisition is the nearly nine-thousand-acre Nonami Plantation, near Albany, Georgia. And like the other 2.1 million acres he owns, he wants to keep it untamed

Photo: Brent Humphreys

Ted Turner always comes out to greet you.

Since I first made his acquaintance in the 1980s, it’s always been the same. He comes out and invites you in.

The greeting is never about him. In our history he’s never been the Great Man Behind the Huge Wooden Desk. Instead, he’s up and working in his Atlanta office, greeting you himself in the outer seating area. Or he’s coming up from a trout stream on one of his properties when he hears your car arrive (until recently, with his wonderful and often creek-drenched Labs, Roxy and Chief). Or he’s just come in from some sort of work on the land.

And then, he always extends his right hand and smiles. Above the smile, and below pale blue eyes that on occasion can focus terrifyingly, there’s always that famous Rhett Butler mustache. His handshake is firm but friendly.

On this day, I’ve arrived at his 8,800-acre plantation outside Albany, Georgia. As I approach the house, walking up the sandy, pea-gravel driveway—beneath the shade of enormous live oaks with rows of azaleas whose blossom pods are getting fat and will soon bloom along the driveway’s edges—he comes out from his study on the main house’s right side.

This is his latest purchase. He bought it from a friend in a “gentleman’s agreement” that if the friend ever wanted to sell, well, Turner just might be in a buying mood. After all, he has been coming here to hunt quail for three decades.

To get to the house, you drive up an almost mile-long single track of sandy gravel. Flights of native quail sail off in clouds from the fields along the roadside as the car crunches past. You know you’re getting close when—after passing several covey fields and forests—you begin to notice horses’ hoofprints in the roadbed sand. Then you see the white peaked barn on the right and its board-fenced paddocks.

This morning, as Turner comes out to meet me, he’s dressed in thorn-proof khakis tucked into tall snake-proof hunting boots. His face is less craggy than in recent years. He seems to have gotten more sleep. At seventy-three, he is still tall and lean. He has a khaki shirt on, the sleeves rolled up his forearms.

“Heyyyyy…how ya been?” he says. He extends his right hand as he comes down the low stairs of the house. “It’s been too, too long.”

Along with the Southern manners and the warm friendliness that resides beneath, Ted Turner has risen to be an American authentic. He is both self-made and unique, and he has made his life into what he wanted through hard work and concentrated thought and constant, focused effort.

Consider this as an example: As a younger man, and a dedicated and sometimes competitive sailor, he decided to win the America’s Cup. Then, according to his son, Beau, he basically sailed and trained his crew and team for two years. And then, Dad went and did it.

These days, that same focus extends far beyond huge silver cups for sailing wins and cable TV networks and New York boardrooms. It’s about improving the quality of the world’s environment and the future of the human beings and animals that live in it.

Photo: Brent Humphreys

Native Ground

A dirt road winds its way through the plantation.

It’s also important to recognize that, thanks to Turner’s business successes, his own private world has grown quite large. He is the second-largest private landowner in the country. He owns 2.1 million acres divided among so many pieces of property that, when he begins to enumerate them offhandedly, the list runs to three pages in my reporting notebook.

Those holdings mostly radiate out from his base in the southeastern United States: his home offices. And many of Turner’s favorite places are in the Southeast. “But, really, come on,” he says. “I like them all, for different reasons.”

In the South, there’s his Hope Plantation in South Carolina, and Avalon, his large and stately place in North Florida, and then “there’s Kinloch, north of Charleston; St. Phillips Island, north of Hilton Head; and in Georgia I have property up in the north for trout fishing,” he says. Not to mention these beautiful, calm, and now by-choice pesticide- and toxin-avoiding acres outside Albany on Nonami Plantation.

“We limit pesticides. We promote natural plant and animal life. Native things. We don’t even kill snakes.”

It’s lovely and has been willfully returned to the way the landscape looked before people set foot on it. There are fields, longleaf pine stands, hardwood forests, and swampy and bosky areas full of wildlife.

The message at Nonami is the same as it is on all of Turner’s landholdings. From the Southeastern states to Montana and Nebraska, from New Mexico to Argentina, there are some specific ideas that are always emplaced. They are land-management programs he believes in, because “it’s the right thing to do,” he says. “We limit pesticides. We promote natural plant and animal life. Native things. We don’t even kill snakes.”

He wants to return this broad swath of land to as natural a state as he can, while also propping up the habitat. At Avalon Plantation in Florida, for instance, his environmental programs have virtually saved the red-cockaded woodpecker from extinction, in part by planting once-common native trees in whose trunk hollows the birds could nest.

It all takes a lot of work and collective thought. Across the properties, there are 300 full-time employees and another 150 seasonal people helping out, the vast majority of whom Turner encourages in other aspects of their lives. He collects their stories (our driver for part of today is a wonderfully friendly guy who grew up and left eastern Europe around the time of the Chernobyl disaster, which we all talk about as we roll over Nonami’s landscape on a tour).

Photo: Brent Humphreys

In the Saddle

Turner prepares for an afternoon of late-season quail hunting on horseback on Nonami.

The employees on the properties eradicate nonnative weed species. They encourage healthy populations of pollinators such as bees and hummingbirds. They support the existing environment. Turner’s reintroduction of native trout to the Cherry Creek watershed on a property in Montana has been held up by the State of Montana as a model of contemporary stream reconstruction. He used jute netting just under the soil to stabilize banks, recontoured streambeds, and planted shade-giving shrubs along the banks to keep the water cool and provide habitat.

With all this effort and these resources, it’s not Ted Turner’s owning the land or even managing all this property that is most striking. Instead, it’s leadership by example. “Everyone can do something,” he says. “Pick up trash on the street. That’s not hard….And you should do it anyway. I do it myself, all the time. Along the roadside. On the sidewalk. Or feed birds. And don’t use so many pesticides. You know, make the world just a little better.”

Over and over, what Turner ends up talking about in long conversations is not what he personally owns but what as humans and animals we all own together. “The atmosphere is common property,” he has told me repeatedly across the years. “The oceans are common. We need to help the world preserve them.”

Nonetheless, once you enter Turner’s world, his relentless agenda is pretty much the way. But it’s always fun. Three minutes after I walk into the house at Nonami, for instance, we’re sitting down in the dining area: It’s lunchtime. Fresh fruit. Iced tea and ice water. And an amazingly tasty quail hash in a sauce ladled over a light and loose cornbread.

As we eat, he’s already talking in his usually quotable way. “I’ve been thinking less about the land in recent years,” he says. “And I’ve been thinking more and more about nuclear weapons. Because, you know, if we don’t get rid of them, they might get rid of us. It’s pretty simple when you look at it that way.”

In fact, if there’s a leitmotif when talking with Turner, it isn’t about what he’s accomplished personally. Through some pretty tough negotiating, he turned his father’s Georgia billboard company around. Then he broadened it into a TV broadcast entity, then converted it into a cable-TV behemoth that oozed into other things (like owning the Atlanta Braves and Atlanta Hawks), which monetized him to exercise his real interests. Through it all, he’s always been relentless. “It was just one step ahead of the other,” he says.

“Nothing too hard. At any one time, just step after step.”

You understand, of course, that it was harder than that. There was a financial scrape when he bought the MGM film libraries in the late 1980s. But these days, that’s all behind him. There were the 6:00 a.m. calisthenics that he drove his America’s Cup team to do every day in the front yard—with him participating, too. There were tensions with cable-TV distributors. The worries. The decision to plant more than one million longleaf pine trees on his properties in the Deep South, “because, well, historically we cut them all down, and they are a critical part of the environment in this part of the world.”

The guy, while clearly having an enormously good time in his day-to-day existence, still has a lot on his mind.

Lunch is over. But Turner still wants to talk. “We’re just trying to return the land to what it was,” he says. “Make it as natural as possible.”

Mostly these days, along with getting rid of the planet’s nukes, he worries about the rise in population and the volume of resources the world is using less judiciously than it might. He worries about whether renewable power is going to work, whether solar and wind energy will make enough of a difference.

Photo: Brent Humphreys

The horse barn.

Why the fixation on environmental problems?

“When I was a boy, back when we lived in Cincinnati before we moved to Georgia, I used to be fascinated by bison,” he says. “There were still two hundred thousand of them—down from millions of them—and by the time I was an adult, they were almost extinct. And as a boy I would read about them. At the house, growing up, we had a pretty extensive collection of books. And I read everything. I liked reading books on biology. About the environment. About birds and plants.”

The afternoon is beginning in earnest now. After a quick post-lunch rest and a checking of messages and the like, as Turner drives us out to an area of the plantation for a few hours of quail hunting before he heads back north to Atlanta and work, there are a few loose ends to tie up. A few last questions.

Does owning all this land sometimes wear him out?

Turner, who is driving a plantation-owned dark green and unobtrusive Chevy Suburban toward a hunting wagon with mules pulling it (the pointers for this afternoon’s hunt are in metal cages beneath the wagon’s seats), pauses and thinks a moment. Then he nods a quiet affirmative.

He smiles. “Yeah,” he says. He smiles again. “Yes…it does.”

“Okay, then,” I say. “I guess there’s just one last question….Do you feel lucky?”

In his hunting gear, ready to go for a walk across a Georgia-quail grain field beneath a blue late-winter sky on land that he owns and maintains to prime conservation standards,

Turner cracks the smallest version of his trademark grin.

Photo: Brent Humphreys

A mule-drawn cart is readied for quail hunting.

He doesn’t have to think about it much. He knows the answer. But he wants to have a little fun with the idea.

He nods. “Yeah, yeah,…yes,” he says. “Yes, I do feel lucky….Ya know, I mean, I’m lucky I wasn’t born a mosquito….Lucky I didn’t get cancer. I’ve lost a lot of friends to cancer.

And I have been lucky. But you have to work at it. You have to work at your life, you know?”

He brakes the Suburban in the golden field to park it in the tall grass behind the mule wagon. There are saddled horses, too. Mike Finley and Ray Pearce, managers of the plantation, are there, waiting. One horse has a long brown-leather sheath on its flank that holds Turner’s shotgun. He walks toward the horse. Everyone is ready to get busy in the fields. The dogs are excited. Everyone feels something is set to go. Gold fields and blue sky and dogs and horses and an afternoon devoted to this place.

And you can tell, as Ted Turner gets out of the vehicle and takes the whole scene in, that he is also privately pleased by what he sees. You can tell even he is a little amazed by it all.