Food & Drink

Julian P. Van Winkle III: The Arbiter of Taste

Go into the tasting room with a third-generation whiskey man

Photo: Joe Pugliese

Lots of people are mad at Julian P. Van Winkle III. Van Winkle is the president of the Old Rip Van Winkle Distillery, whose aged bourbons a growing body of aficionados believe to be the finest whiskeys on Earth. The trouble is that demand for his Pappy Van Winkle’s Family Reserve bourbons has lately swollen in exasperating proportion to supply. He releases between 6,000 and 7,000 cases per year, “about what Jim Beam puts out in ten minutes,” Van Winkle says. “We’re the opposite of the Walmart business model: high profit and almost no volume at all.”

The scarcity is making bourbon lovers desperate, cranky, and poor. On eBay, Van Winkle bourbons routinely command upwards of $500 a bottle. Pappy turns up on bar menus in Van Winkle’s hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, for as much as $60, usually alongside the caveat “WHEN AVAILABLE.” The bourbons are distributed to liquor stores only twice a year—in spring and fall—and a half dozen, give or take (bottles, not cases), is the average allocation. The bottles rarely touch the shelves, instead going straight to customers whose names have been on waiting lists for months or years.

Photo: Joe Pugliese

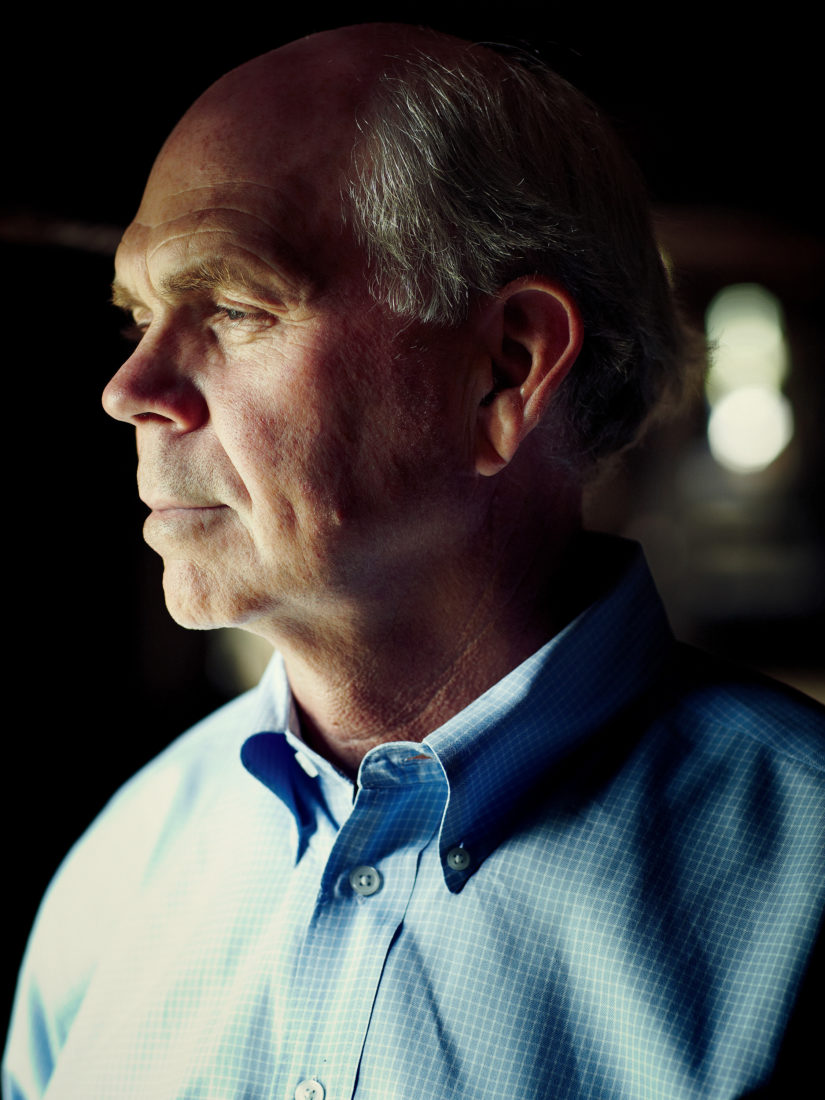

Tastemaker

Julian Van Winkle prepares to sample some of the latest Pappy to emerge from the barrels.

So much bother for a sip of whiskey does not endear Van Winkle to the drinking public, or to shopkeepers, one of whom not long ago bodily attacked Van Winkle’s sales agent for showing up with too meager a delivery. “It can get dangerous,” says Van Winkle. “In Michigan, a guy physically ran our sales rep out of a store because he didn’t get but two or three bottles. He was so damn angry about it. Threatened him with a shoe or a gun or something. I’ve never had to deal with that kind of thing face to face, but I’m sure it’s coming someday.”

One does not want to imagine what rashnesses Pappy fans might be moved to if they could see what Julian Van Winkle is doing with his bourbon this morning: He is spitting it out. Pints upon pints, pinging into the spittoon in a practiced, laminar stream.

A visiting journalist is frankly appalled to see greatness treated so brusquely. It’s like watching someone ride a moped through the Louvre. “Hard work, but someone’s gotta do it,” says Van Winkle, sixty-three, whose clear blue eyes and relatively uncreased complexion do not betray a lifelong career of concerted bourbon use.

The desecration is taking place in the tasting room at the Buffalo Trace Distillery in Frankfort, Kentucky. A decade ago, Buffalo Trace (which also makes such venerable labels as Blanton’s and W. L. Weller) began distilling the Pappy Van Winkle recipe, in partnership with Van Winkle. Today, the first batches of Buffalo Trace Pappy are reaching bottling maturity, and Van Winkle has made the forty-five-minute drive from Louisville to undertake what is in fact momentous spittoon duty: to assay whether Buffalo Trace’s handiwork deserves the family name.

Photo: Joe Pugliese

Aging Gracefully

Barrels at Buffalo Trace.

A flotilla of forty-seven partially filled graduated goblets and half-pint bottles—each drawn from a separate barrel—are arrayed before Van Winkle on a lazy Susan. Each barrel requires individual sampling because barrel aging is not an exact science, but an ineluctable, chaotic passage through which the whiskey grows a soul. Seasoned in a charred oak barrel, bourbon acquires its dark complexion and, as it picks up oak sugars in the caramelized wood, much of its sweetness, too. The ratio of barrel staves made from sapwood to those made from heartwood affects the bourbon’s flavor, as do seemingly trifling considerations such as proximity to a window and altitude. “Whiskey on the top floors ages faster,” Van Winkle explains. “We don’t keep our barrels any higher than the middle floors because it’s going to be there so long. It would pick up too much oak.”

As the whiskey ages, it evaporates volume through the wood—10 percent the first year and 4 to 5 percent each subsequent year, an attrition known as the angels’ share. On a twenty-three-year-old barrel, the angels’ share is about fifty gallons out of the original fifty-three, which partly explains Van Winkle 23’s heart-stopping expense. “When it comes to our bourbon, the angels are very greedy,” Van Winkle observes.

Julian Van Winkle’s palate is the ultimate arbiter as to whether a barrel ends up in a Van Winkle bottle. But he is decidedly not a notes-of-pencil-shavings-and-asphalt sort of taster. “Mm, nice and mild,” “Man, that’s so sweet,” “A little bite to this one, a little rough,” are the comments he makes as the table revolves. “I don’t have a schooled palate,” he says. “For me, it’s: ‘This is what I like, and if it tastes like this, it’s all right with me.’”

Van Winkle’s humble manner with a whiskey that critics herniate themselves describing is rooted in an abiding family aversion to high science and cold connoisseurship. His grandfather Julian P. “Pappy” Van Winkle (he appears lipping a stogie on the labels that bear his name) “had a sign at the old distillery that said, ‘No Chemists Allowed,’” Julian says. “He didn’t have a lab, just some litmus paper and a hydrometer to get the proof right. He believed all you need to make fine bourbon are Mother Nature and Father Time.”

In 1893, at the age of eighteen, Pappy Van Winkle entered the whiskey business as a traveling salesman for W. L. Weller. The product he sold in those days was not, strictly speaking, bourbon. According to federal law, straight bourbon whiskey must be distilled in the United States (but not necessarily Kentucky) from a mash of at least 51 percent corn. It must be aged in new charred oak barrels, and it may not be adulterated with any additives other than water. The early Weller whiskeys were “rectified” with flavoring and coloring agents, and proof was often corrected with grain alcohol. Years later, as president of the Stitzel-Weller Distillery, after Pappy had become a vehement, exacting crusader for traditionally manufactured bourbon, he was asked about his early perfidies in the rectifying trade. “There’s no one purer than a reformed prostitute” was his reply.

Photo: Joe Pugliese

The tasting lab.

Through the sixties, Stitzel-Weller bottled respected bourbons under such labels as Old Fitzgerald, W. L. Weller, and Rebel Yell (a different product from the down-market, frat house libation it is today). Van Winkle’s bourbons owed their excellence, in part, to the vast substrate of limestone that filters the local groundwater to uncommon purity, and to Pappy’s recipe. In addition to corn, bourbon generally uses rye as a secondary grain. Pappy’s mash bill called for wheat, a milder, sweeter grain that picks up less barrel char and is gentler to the tongue.

In 1972, seven years after Pappy’s death, stockholders forced the distillery’s sale. Julian had recently returned to Louisville after attending Virginia’s Randolph-Macon College, where he studied economics and psychology. After a stint as a clothing salesman, he joined his father, Julian, Jr., salvaging what could be salvaged of the family whiskey business. Barrels of Pappy’s recipe were quiescently marking time in Stitzel-Weller’s warehouses. Father and son kept the company alive, buying back their own bourbon and bottling it independently under the Old Rip Van Winkle label.

When cancer took Julian’s father in 1981, Julian, at the age of thirty-two with four children to support, made the not-ostensibly-wise decision to continue in the whiskey business, bottling Van Winkle bourbons with his own hands in a flood-prone ruin of a facility he purchased south of Louisville. The 1980s were dark years for bourbon and largely profitless years for Julian. The spirits market had so bafflingly and resolutely forsaken bourbon for scotch, vodka, and gin that the drinking public could be induced to pay good money for bourbon only if it was bottled in a novelty crock resembling a coal miner or a football or a dog. Julian was reduced to trafficking in these gimcracks for about a decade and a half. Then, in 1996, a Van Winkle sales rep submitted bottles of Van Winkle 20-year to the Beverage Testing Institute, a prestigious Chicago-based wine authority. The Pappy Van Winkle 20-year-old got a rating of 99, an unprecedented number for any whiskey, scotch, or bourbon. An avalanche of demand and acclaim followed, concluding most recently with a James Beard Foundation award in 2011.

Photo: Joe Pugliese

Good Grain

A handful of the ground corn that’s used to make Pappy.

Do the Pappy whiskeys deserve the fervent hype and covetousness? I put the question to bourbon enthusiast and fellow James Beard winner Sean Brock, chef at the celebrated Charleston, South Carolina, restaurants McCrady’s and Husk. “What I should say is, it’s the worst bourbon in the entire world. It’s a rip-off; don’t buy it. But, no, for me, it’s an obsession. You can taste the patience, the care, the craft. You know you’re tasting something that’s been aged properly without cutting corners. Their [motto] says it all,” adds Brock, citing a creed stamped on a plaque that Pappy hung at the entrance of the Stitzel-Weller distillery: “‘At a profit if we can, at a loss if we must, but always fine bourbon.’ If more people looked at their business models that way, America would be a much cooler place to hang out.”

When Julian Van Winkle has sipped his way through the morning’s forty-seven barrels, I prevail on him to share a splash or two from some bottled vintages, a tempting selection of which—a 15-year, a 20-, and a 23-—stand on a nearby shelf in the tasting room. He passes me a glass with a modest amber dose of the 23. “It’s too oaky for some, but I like it,” he says. I put my snoot into the glass. It is not too oaky. It is supple, warm, and suffused with an intelligent sweetness. It tastes like the realization of an ideal all other bourbons I’ve had aspire to with incomplete success. I can say that I pick up notes of vanilla, butterscotch, and assorted citrus fruit, but I don’t write about citrus notes in my little notebook. What I jot are some raptures too fatuously sentimental and foolish to reprint and which are anyway irrelevant to the matter at hand. I mention the goofy mawkishness good bourbon inspires only to note that good bourbon is a weird thing—a fluid that thrills us and rouses the soul by means defiant of connoisseurship and not wholly related to alcoholic intoxication. The late Louisiana novelist Walker Percy made a brilliant study of this phenomenon in a short essay, a copy of which I’ve brought along in my pocket. There in the tasting room, I read a few lines aloud to Mr. Van Winkle.

“The joy of bourbon drinking is not the pharmacological effect of the C2H5OH on the cortex but rather the instant of the whiskey being knocked back and the little explosion of Kentucky U.S.A. sunshine in the cavity of the nasopharynx and the hot bosky bite of Tennessee summertime—aesthetic considerations to which the effect of the alcohol is, if not dispensable, at least secondary.… Bourbon does for me what the piece of cake did for Proust.”

“A bourbon and what?”

The passage carries Van Winkle into memories of his childhood sickbed when his parents plied him with honeyed bourbon (“good frickin’ bourbon, old Stitzel-Weller, probably made in the forties”), and of young parenthood, when he would serve straight 107 proof to his sick children—a son and a triplet litter of daughters. “We had to knock those kids out, or nobody got any sleep.” We drink the 20-year, the 15-, leaving the spittoon be. A long unremembered moment returns to me: my first drink with my late grandfather. I ordered a bourbon and Coke. He made a face like I’d called him a name. “A bourbon and what?” he said. I have not revisited the barbarism since.

By the end of the day, Van Winkle has made his way through another full program of samples, with better results than he’d expected. Pappy’s future looks sound: out of ninety-four barrels, “only one dog in the bunch.”

On the road back to Louisville, I ask Van Winkle why, with a high-volume distillery in his corner and the public in full ferment for his product, doesn’t he seize this moment to crank the stills to capacity and cash in? “Well, the quality would go down,” he says, as though this is explanation enough. “I don’t need a ton of money. I’m comfortable. Why get bigger? I mean, yeah, I guess I’d like to have a jet to fly around in, but things like that just complicate your life.” He does, however, have some happy news for anyone who has yet to lay hands on a bottle of Pappy: Production is expanding. Not by much, just 2 to 3 percent a year. Not to try to make a killing, Van Winkle says, “just to try not to have quite so many people mad at me.”