Sporting

On Chalk Time

For the fly angler, a trip to the fabled streams of England just may be the pinnacle of the sporting life

Photo: WILLIAM HEREFORD

The author takes a siesta on the banks of the Itchen after landing a memorable catch.

If you are a trout angler or aspire to be one, you owe it to yourself to visit at least once the chalk streams of England. Granted, New Zealand, Argentina, and Kamchatka beckon with marvelous trouting, but my aim here is to tell you why the fishing on the English chalk streams may very well be the most variously satisfying version of that sport to be had anywhere in the world.

There are numerous reasons for this, but let us begin with a bit of hydrology. The chalk streams take their name from a subsoil band of calcium carbonate, or “chalk,” formed of compacted shells a hundred million years ago when the British Isles lay under three hundred feet of ocean. This band runs for some three hundred miles through England, from Yorkshire in the north to Dorset in the south, and chalk streams are born when the plentiful English rain seeps through the chalk into an aquifer and then is forced back to the surface as springs, which join to become streams.

Photo: WILLIAM HEREFORD

A striking brown trout in hand.

Emerging at a constant 50°F, filtered by the chalk into stainless clarity, high in alkalinity, rich in nutrients, and all but impervious to drought and flood, the streams are nothing short of perfect trout habitat. They are also soul-fillingly beautiful, in what the English chalk stream devotee and angling writer Charles Rangeley-Wilson calls their “verdant opulence” and “sedate grandeur.” Ambling elegantly through idyllic green valleys, rich in starwort, water celery, ranunculus, and other trout-food-nurturing weeds, they are, in Rangeley Wilson’s deft description, “constant, equable, cool, fertile.”

Photo: William Hereford

A bird’s-eye view of the Test.

There are over two hundred of these streams in England, ranging in width from ones you might jump across to some that are sixty to eighty feet wide, and in renown from world-famous to ones known only to a handful of locals. Some are intensely managed and manicured; others are left as nature made them. Some contain only wild populations of brown trout and grayling, while others are supplemented with stocked browns and rainbows. On all of them the fishing rights are privately owned and leased out to individuals, syndicates of anglers, fly shops, or water brokers who then sell those rights as “beats,” or sections of the stream, on a daily basis to an allotted number of rods per beat. The price per rod per day can vary from as little as lunch money on the lesser-known chalks to upwards of a thousand dollars on the legendary ones.

With all that bewildering variety to choose from, on my first visit to the chalk streams over a decade ago, my friend Tom Montgomery and I opted to experience as much of it as we could in ten days and fished that many streams from Dorset on the southern coast to the northern shores of Norfolk, in the eastern part of the country. For my second trip—taken this past May with my wife, my daughter, my niece, and a group of hearty, trout-loving friends—I decided we would limit ourselves to my five favorite streams from the previous trip: the Kennet in Berkshire, the upper Avon in Wiltshire, the Bourne in Hampshire, and, also in Hampshire, the respective king and queen of chalk streams, the Test and the Itchen.

Photo: WILLIAM HEREFORD

From left: Enjoying a post-fishing cigar; Sandal, a Labrador retriever owned by William Daniel, surveys the action.

The latter two are arguably the two most famous trout waters on earth, despite there being numerous rivers around the world where more and bigger trout are caught. They are uniquely legendary because men have fished them for at least four centuries, and in the past two centuries many of those men have written voluminously, well, and to a worldwide readership about that angling. One of their most determined chroniclers was an assiduous Victorian gentleman named F. M. Halford, who in the last two decades of the nineteenth century adopted them as a laboratory in which to develop and refine the art and science of dry fly fishing for trout. In two books and many articles for The Field magazine, he made a cult of that method of fishing, with himself as high priest. In addition to dispensing revolutionary specifics on the dressing and use of dry flies, Halford took it upon himself to codify for his readers a proper behavior for that use—a sort of etiquette of on-stream comportment that pays equal respect to both the trout and other anglers. That etiquette has proved to be as durable (it is still practiced today to one degree of strictness or another on the Test, the Itchen, and a few other chalk streams) as it has nontransferable (those streams are the only places on earth where it is practiced).

“So, what do I do and not do here?” I asked my guide on my first visit to the Test.

“You don’t get in the water,” he said. “We fish from a mowed path along the bank. Cast only upstream, of course, and altogether with dry flies. That should do it.”

To be honest, it seemed a bit prissy, and designed to catch as few trout as possible. But by the time that trip was over, I had come to love Halford’s code of manners, and to agree with J. W. Hills, the author of the delightful 1924 book A Summer on the Test, that it had produced “the most finished school of fishing in the world.”

Photo: WILLIAM HEREFORD

From left: A fine hat made better by an ever-growing collection of dry flies; guide and angler pass Heale House on the way to the river.

The Itchen / Day 1

“Gold dust” is the way William Daniel describes the Itchen beat we are on today. “If it ever came up for sale, which it won’t, it would go for more than two million pounds a mile.”

He ought to know. Daniel is one of England’s top water brokers and has provided our group with the beats we are fishing over the next five days. A former London investment banker and graduate of Eton and Cambridge, he started his company, Famous Fishing, twenty-seven years ago to “access the inaccessible” in chalk stream angling and wing shooting. A robust sixty-two, he is a large, chatty, boyishly keen and charming man, a deadly trout fisherman, and as much fun on a stream as anyone I know.

Leaving two of our group with a guide on the beat below us, Daniel, the photographer William Hereford, and I walk slowly upstream along a small path, looking for rises. It is a pluperfect May morning, clear and warm. A swan swims ahead of us trailing four cygnets in her wake. Wood pigeons coo, and reed warblers start from the brush bordering the stream, which here is some three to four feet deep and twenty to thirty feet across, a smooth, clear, even flow over a gravel bottom and ranunculus weed that waves in that flow like a woman’s hair let out in a breeze.

Photo: WILLIAM HEREFORD

From left: A group sets off for a morning of action; dry flies on a river keeper’s vest.

“Study to be quiet” are Izaak Walton’s concluding words in The Compleat Angler, and on no trout water I know of is that injunction better advice today, almost four hundred years after it was written, than on this, Walton’s home stream. Part of the reason the Itchen is so highly valued is that it is not stocked, and the angling for its wild, world-weary brown trout, which have seen it all for centuries, is as challenging as it gets. A good day for a seasoned angler here might give up four trout. Unless, that is, she is here during the mayfly.

I had timed our trip to coincide with the annual mid-May to early-June hatch of a large, juicy insect named Ephemera danica but referred to on the chalks simply as “the mayfly.” The short but profuse airborne life of this bug, occurring over roughly a two-week period that varies a bit from year to year, causes the normally discriminating chalk stream trout to gorge themselves with such recklessness that the period is known as the Duffer’s Fortnight.

Alas, for this duffer on this morning, there are no danica on the water or in the air. In fact, there are few observable insects of any kind. So, this being the Itchen, I do not tie on the nymph I would normally prospect with, but a small Parachute Adams dry fly instead. And after just under a half hour of walking slowly, as far away from the bank as possible, with frequent stops studying to be quiet and scanning the pools ahead for rises, we find a trout to try it on.

Photo: WILLIAM HEREFORD

From left: A reminder that the chalk streams are private; tools of the trade.

But, this being the Itchen, the fish is rising in an all but impossible lie to reach with a fly. For one thing, that lie is directly underneath an overhanging willow branch; for another, even though I get into the stream (allowed on this beat of the Itchen though not on others) and wade up to within casting range, another willow branch behind me makes an aerial cast impossible.

“You’ll have to roll cast to him,” Daniel says with relish from the bank.

“But I can’t see,” I answer pathetically, mouthing the bitter pill of anticipated failure on the first trout of the trip.

“What do you mean you can’t see?” he thunders.

“The sun, William. Everything ahead of me is in glare.”

“Just roll out a cast or two, that’s the boy. I’ll tell you when you’re on him.”

I will spare you, patient reader, the repeated “Two inches to the right” and the “No, no, no! Too far left”; the take that I cannot see and strike too late; then the wait, with slim hope that the trout has not felt the hook; the five changes of flies…I will tell you only that this lovely three-pound Itchen brown comes back finally to a tiny Iron Blue, and that it is one of the most gratifying catches of my life.

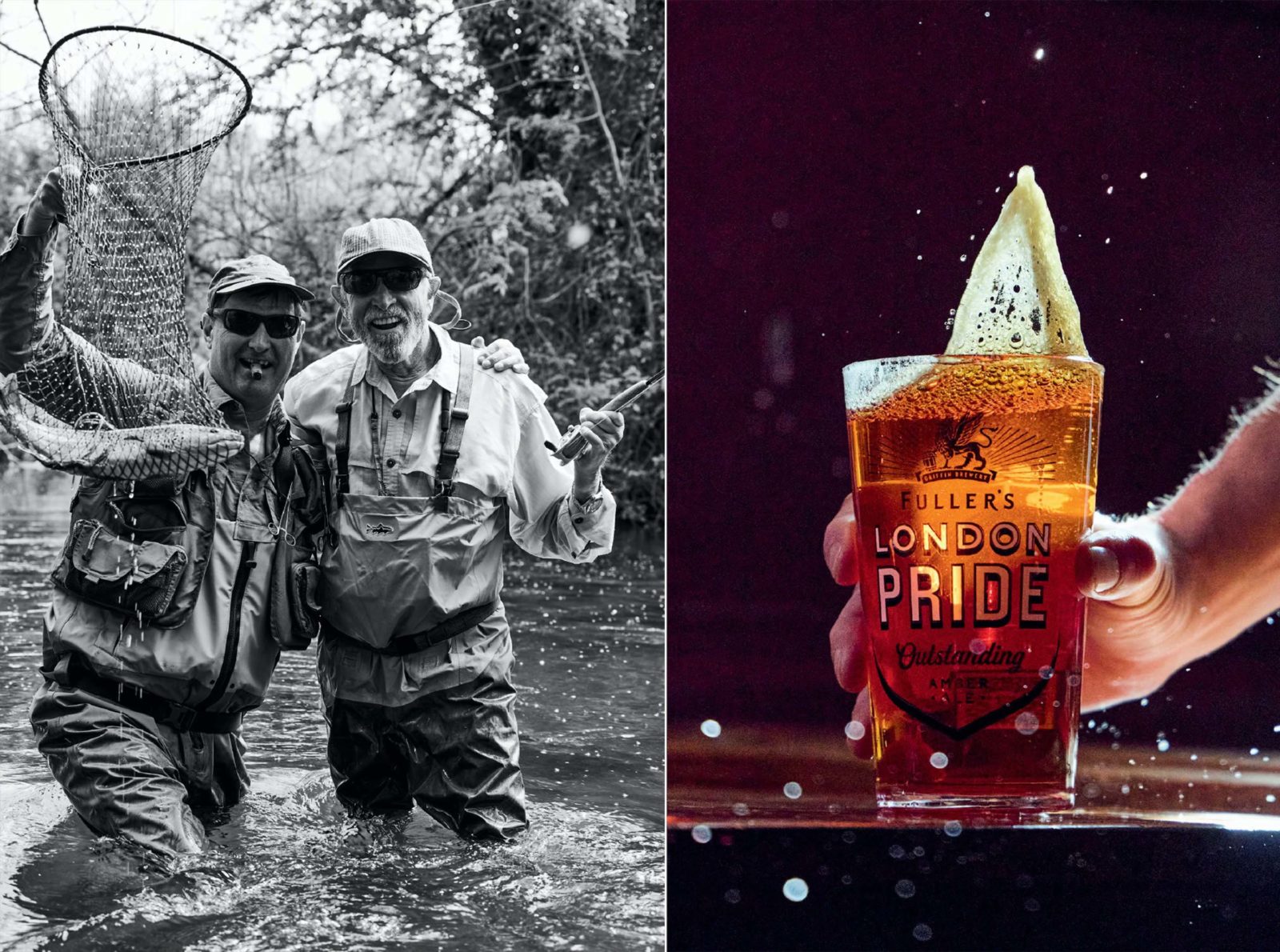

Photo: WILLIAM HEREFORD

From left: Daniel and the author celebrate after landing a beautiful brown on the Itchen; a beer hits the spot in Winchester.

For our entire stay in Hampshire, we enjoy perfect weather and the myriad pleasures of the rose-covered English countryside in May. We split our visit between the instantly lovable towns of Stockbridge on the Test and Winchester on the Itchen and have very good lodging and food in both—at the Grosvenor hotel in Stockbridge, and in Winchester at the Wykeham Arms, which has welcomed hungry and thirsty travelers to its peerless pub since 1755.

Our group includes two women who do not fish and two who will fish for only two days. For them, William Daniel has designed a separate itinerary that includes a guide and van transportation each day to nearby sites of interest. They visit Stonehenge and the famous water gardens at Longstock Park, walk cobbled streets in the World Heritage Site city of Bath, and have a look at the original Magna Carta at Salisbury Cathedral. Much as I enjoy the fishing, I feel a twinge of jealousy each morning when these “non-anglers” venture out for more world-class sightseeing. And so, on the fourth day, I join them for a walking tour of the ancient city of Winchester, the first capital of England.

Photo: WILLIAM HEREFORD

A peacock holds court near premier chalk water.

Our guide is Lady Sally Peel, a tall, graceful woman with one of those fine English faces mixing steely resolution with amiability, whose husband, departed from this life at 101, had been the queen’s obstetrician. Peel is seventy-one, with a quick mind, an endearing smile, and an encyclopedic knowledge of Winchester. With her lecturing learnedly at each stop, we visit the house where Jane Austen lived out her last days and died in 1817; and then Winchester College, a school for, she tells us, “the cleverest boys in England,” founded in 1382. But the crown jewel of the tour is Winchester Cathedral, an enormous amalgam of Gothic, Norman, and Romanesque architecture whose construction, in the shape of a cross, began in 1079, though a church existed at that site four centuries before that.

I could happily have spent two or three days in the cathedral’s great vaulted rooms, paying homage to Jane Austen and Izaak Walton, who are buried there, looking at some of the oldest of the great medieval quires in England; the high altar fronting a lovely fifteenth-century screen; the magnificent twelfth- and thirteenth-century wall paintings of Christ’s passion in the Holy Sepulchre Chapel. And I could have as happily spent another full day wandering around the cathedral’s library of rare books and illuminated manuscripts. But, of course, there is fishing to be done. And despite the absence of danica, that fishing is better than good everywhere we go, and some of it unforgettable.

Photo: WILLIAM HEREFORD

Johnny Johns confers with his guide.

The two and a half miles of the River Avon at Heale Estate is as close to the Paradise of Anglers as I ever expect to get. Running through twelve hundred green acres of sheep-dotted meadows and parkland, and overlooked by the magisterial Heale House, a sixteenth-century manor house where King Charles II hid from parliamentarian troops on his flight to France in 1651, the river has not a hair out of place, and its flow is so entrancingly sedative that one might forget one is there to fish.

That is, if one didn’t have a daughter like mine, who possesses an osprey’s single-mindedness of angling purpose. “Why are you two just standing there?” Greta says to me and my great friend Nana Lampton, who, like me, is thirty years Greta’s senior and who does not have to study to be quiet.

The three of us are sharing two rods for the morning without a guide, which means I am there mostly to tie on flies. As Nana and I follow Greta to the bottom of our beat, peacocks shriek from the grounds of Heale House, a supine pig grunts in its sleep, pheasant fly from the meadows to the hedgerows, and mallards flush from the stream ahead of us.

We spend the entire morning fishing less than a half mile of the Avon, I and these strong, accomplished women whose company I cherish, two of five gracing the Avon this day. Watching Greta and Nana pick off trout after rising trout in this ineffably pleasant place, I am awash in one of the overwhelming surges of gratitude to which, in my dotage, I am given; and moved as well to feel more than a little sorry for Halford and his Victorian buddies who did not countenance women on the streams.

Photo: WILLIAM HEREFORD

A chalk stream meanders through the countryside.

Photo: WILLIAM HEREFORD

A brown trout prior to release.

The Test / Day 5

Every fishing trip has for me a defining occurrence of unmistakable emphasis in which people, place, and action come together, like lightning in a bottle, into a meaning that encapsulates the entire journey.

The most efficient way to harvest trout in a stream is to dynamite it. In Izaak Walton’s day, the preferred method was to spear the chalk stream trout at night by torchlight. Then followed netting; using trotlines and blowlines, the latter a form of dapping with live insects; fishing with minnows and worms. But men, to paraphrase W. B. Yeats, are in love with what is difficult, particularly those who over the centuries have come to fish for sport over sustenance. With Halford and his acolytes, finding elegant solutions to difficult trouting problems overrode necessity as the mother of invention, and they replaced the sunk brace of wet flies fished downstream of the generation preceding them with upstream and dry, along with a formidable knowledge of entomology.

The big trout my friend Johnny Johns and I are looking at is not rising, but it is “on the fin,” meaning suspended in the water column and active. (No gentleman, of course, is discourteous enough to fish for a trout lying doggo on the bottom and clearly in no mood to be fished for!) And by its darts from side to side and glimpses of its white mouth opening, we know that this one is feeding—but on subsurface nymphs.

Johnny and I are on a carrier stream, or side channel, of the hallowed waters of the middle Test, on my favorite of all the chalk stream beats I have fished, a beat that is dead man’s shoes: all but inaccessible, though accessed by William Daniel, and so exclusive it can’t be named. Again, it is a flawless day; again, there are few bugs in the air or on the water, and no sign of danica. (Though it must be mentioned that that very evening, on this very beat, “the mayfly” began. And those in our group who were there for it witnessed what one of them, a widely traveled angler, called the greatest experience of his fishing life: clouds of danica spinners everywhere in the air; the trout-rises for them, as they deposited their eggs and fell dying to the water, like rain pocking the calm flow of the Test; and dry fly fishing that duffers and experts alike dream of.)

Photo: WILLIAM HEREFORD

From left: Nana Lampton and Peter Major of Heale House make their way to the water; one of Daniel’s antique fly reels.

Johnny and I have each caught a rising trout, after numerous fly changes, on a tiny black dry I had in my box that both trout took indifferently and only after three or four drifts over them. Johnny is a Harvard Law whiz of the insurance industry and a black-diamond angler, but, in short, we don’t know what we are doing. We do, however, know how to do it, and at this point in the trip neither of us would dream of doing it otherwise.

Johnny puts the fly perfectly over the fish numerous times to the trout’s utter disdain.

“Too bad. We could catch him on a nymph.”

“But of course we won’t.”

He reels in and we are leaving to find another fish when big, voluble William Daniel walks up behind us with his yellow Lab and an ever-present unlit cigar clenched in his teeth. We tell him about the unobliging trout. He asks to see Johnny’s fly and promptly snips it off. “I’ll tell you what,” he says, pulling a fly box from his vest. “I believe the mayfly may start soon, today or tomorrow. The conditions are just about right, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the fish are onto that and might start looking up for them. Let’s try your chap with one of these.”

Photo: WILLIAM HEREFORD

The group dines at the Greyhound Pub in Stockbridge.

Then, holding out a danica imitation, a Cream Wulff modified to his specifications, he proceeds to give Johnny and me as learned a streamside tutorial on chalk stream expertise as any Halford might have given: on how trout look for certain markers to identify an insect; how the black at the base of the tail of his fly exactly matches that on danica; how the badger hackle is dyed black where it meets the body to match that junction on the bug.

“Those things are markers for the trout, you see. And they key a stronger response than would a fly that might look to you and me more like the real thing.” With that, he ties the well-marked Wulff to Johnny’s tippet and we revisit our chap.

Photo: William Hereford

From left: Ranunculus blooming in a chalk stream; a fly box loaded for trout.

Watching Johnny kneel and strip out line, I seem to see Halford himself, or the legendary angling writer Francis Francis, or the greatest chalk stream angler of them all, George Selwyn Marryat, kneeling there in jacket, tie, and plus fours, having compressed decades of hard-won knowledge—of all the minute and intricate interdependencies of stream, insects, and trout—into the fly at the end of his leader. And there it is—the lightning in the bottle! As Johnny makes one false cast and lays the fly on the water, all the glorious history, culture, science, and art of the chalk streams coalesce for me into as vivid, if untranslatable, a vermiculate scroll as that on a brown trout’s flank.

This one weighs four pounds, and Johnny catches it, upstream and dry, on his very first cast.

If You Go

The two-week period from mid-May to early June known as the Duffer’s Fortnight is by no means the only time when good dry-fly fishing may be had on the English chalk streams. There are prolific hatches of insects throughout the summer, and fishing the dry fly (as well as nymphs wherever they are allowed) can produce excellent results anytime from May to October. famousfishing.co.uk