Home & Garden

See Inside the Splendid Home Kitchens of Three Southern Food Pros

Each transformed their family kitchens into deeply personal spaces, designed just as much for living as for cooking

Caroline Chambers’s Cozy Cottage Kitchen

Credentials: Author of the Substack newsletter and best-selling cookbook What to Cook When You Don’t Feel like Cooking

Photo: ERIN KUNKEL

A backsplash of Tabarka Studio tile surrounds the Kohler sink; Caroline Chambers stands at her Café Appliances stove, surrounded by cabinets she drenched in Sherwin-Williams’s Green Onyx; Chambers enlisted Raleigh interior designer Kate Hutchison, who designed the cozy dining nook with a banquette upholstered in striped Kravet fabric.

Caroline Chambers’s half million Substack followers know she’ll make the most of what she has on hand. No yogurt? Sour cream is fine! Out of soy sauce? Grab Worcestershire instead. “My mom was the queen of substitutions,” says the Winston-Salem, North Carolina, native. “She would get home to three kids after a long day, and just swap in whatever she had and throw together these pantry meals. I’m very much emulating that in my own kitchen.” When it came to renovating her 1960s cottage in Carmel, California—which she shares with her husband and three (soon to be four) young children—it was all about making the tiny kitchen the hub of the two-thousand-square-foot home. They knocked down walls, added a bar counter, and situated the stove on the island rather than against a wall so Chambers can interact with the family while she cooks. Each night the kids pull up barstools, chatting about their day and “helping” with prep. Then they all pile into the adjacent kitchen nook to eat. “We do everything there because it’s such a small house,” she says. “It’s the dining room table, it’s the breakfast table, it’s the craft table. That kitchen table is very much where we live our lives.” To temper the chaos, Chambers prioritized organization, with meticulously curated spice and utensil drawers flanking the stove and large drawers (rather than cabinets) to store pots and pans. And a nonnegotiable is keeping the space tidy. “It’s my Southernness coming through,” Chambers says. “I always hear my mom in my head saying, ‘You never know who will stop by.’”

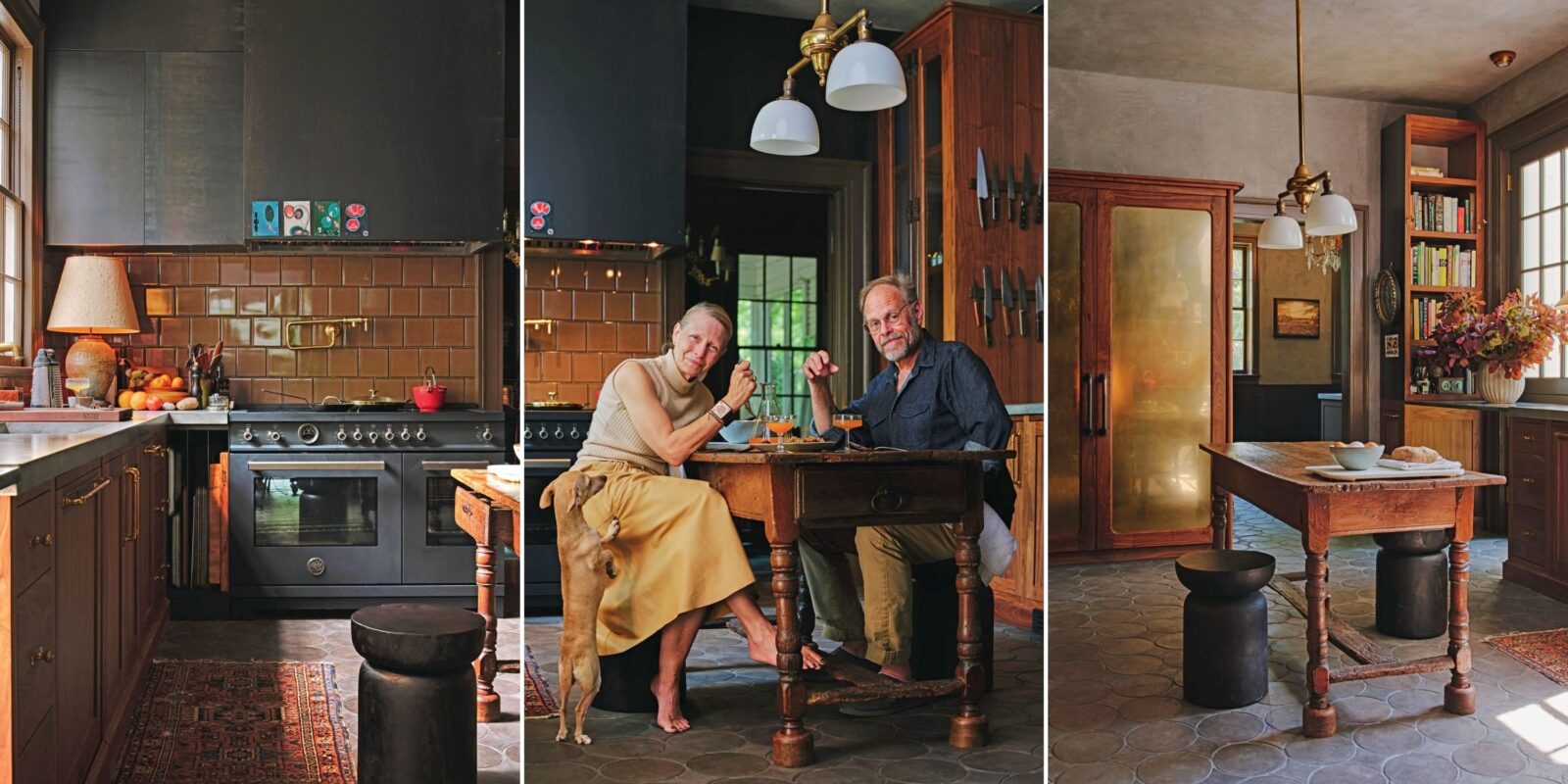

Alton Brown’s Rebel Chef’s Kitchen

Credentials: Former Food Network personality and author of numerous cookbooks and Food for Thought, a new collection of personal essays

Photo: ANDREW THOMAS LEE

Alton Brown in his Atlanta kitchen with his beagle mix, Hamlet.

Photo: ANDREW THOMAS LEE

A Miele ventilation hood, adorned with artwork by Elizabeth Ingram, caps the Bertazzoni induction range; Ingram, Brown, and Guillermo, their Italian greyhound/ Chihuahua mix; an antique French farmhouse table and a panel-ready GE Monogram refrigerator, which Ingram outfitted with walnut-and-brass doors, anchor the room.

Despite his career as a professional chef, Alton Brown despises the ubiquitous dream kitchen with a big island and stainless-steel appliances. “It’s a metal that, to my mind, exists only to be cleaned,” he says. So in 2023 when he and his wife, the restaurant designer Elizabeth Ingram, took over her parents’ 1920s English country–style house in Atlanta, they gutted the 1980s kitchen and reimagined it as a furnished room that they happen to cook and eat in. “We love rich material—walnut, concrete, brass, and terra-cotta tile,” Brown says. “It’s the kind of kitchen Jules Verne might have had, built around a well-worn eighteenth-century French farmhouse table, which is the center of the kitchen and, honestly, the house.” While Ingram, whose portfolio includes Marcel in Atlanta and Chubby Fish in Charleston, South Carolina, led the charge on the design, Brown had some requests: good ventilation, a large sink, attractive but useful lighting, and plenty of power along the counters. “We also needed cookbook storage with a spot by a window to read.” And in another unconventional pro-chef move, he opted for an induction stove. “I thought it would be difficult to give up gas, but it wasn’t at all,” he says. “The kitchen is cooler and cleaner, and all the steel and iron we cook with couldn’t be better suited.” Well-worn skillets hang on the wall like art. “One cast-iron skillet came from my great-grandmother, who was the first cook I watched fry chicken,” he says. “Nothing else gets cooked in that thing. It’s probably seventy-five percent schmaltz at this point.”

Photo: ANDREW THOMAS LEE

Heirloom skillets complement the walnut cabinets.

Annie Colquitt’s Minimalist Mountain Kitchen

Credentials: Co-owner of Cataloochee Ranch in Maggie Valley, North Carolina, and the Swag in Waynesville

Photo: TIM ROBISON

Textured cabinets painted in Farrow & Ball’s Green Smoke and a Visual Comfort pendant light frame the centerpiece window; Annie Colquitt.

Photo: TIM ROBISON

A bird sculpture hangs on the hood above the BlueStar range; viewed through the open window, shelves hold Colquitt’s collection of East Fork pottery.

When Annie Colquitt and her husband, David, purchased a 1986 mountain house between their two popular Western North Carolina resorts, it was loaded with potential—and birdhouses. “The previous owner had a collection of more than thirty of them, so we started calling it the Birdhouse,” she explains. “I think of it as a nest for our family, a refuge and a place where my kids can squawk all they want.” The centerpiece of the 2,500-square-foot second home is a minimalist kitchen, intentionally designed to contrast with their bustling primary residence in Knoxville, Tennessee. “I wasn’t thinking of entertaining people in this kitchen,” Colquitt says. “It’s for us.” To create a bright, peaceful space, she emphasized the stunning mountain views. Behind the sink, a long accordion window opens completely to the landscape beyond, with stools on the opposite side from which the kids can place their orders for pancakes or homemade ice pops. The cabinets have finger pulls instead of knobs, a tranquil green finish, and a rough texture to mesh with the wood walls throughout the house. Colquitt opted for open shelving to display her collections of East Fork pottery and daffodil vases by Knoxville glass artist Tommie Rush. “I could not pull off exposed shelves at home because they would always be a mess,” she says. “I think this is why I feel so at peace here. Less stuff just feels like freedom.” On the stove hood, Colquitt mounted a large bird sculpture she found at a gallery in New Mexico. “It feels like it was meant to be here—at the Birdhouse.”

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book.