Sporting

The Amazonian Sporting Trip of a Lifetime

Deep in the jungle of the Amazon Basin lies a surprisingly well-appointed lodge, where the only thing that tops the amenities just might be the fishing

Photo: Eric Kiel

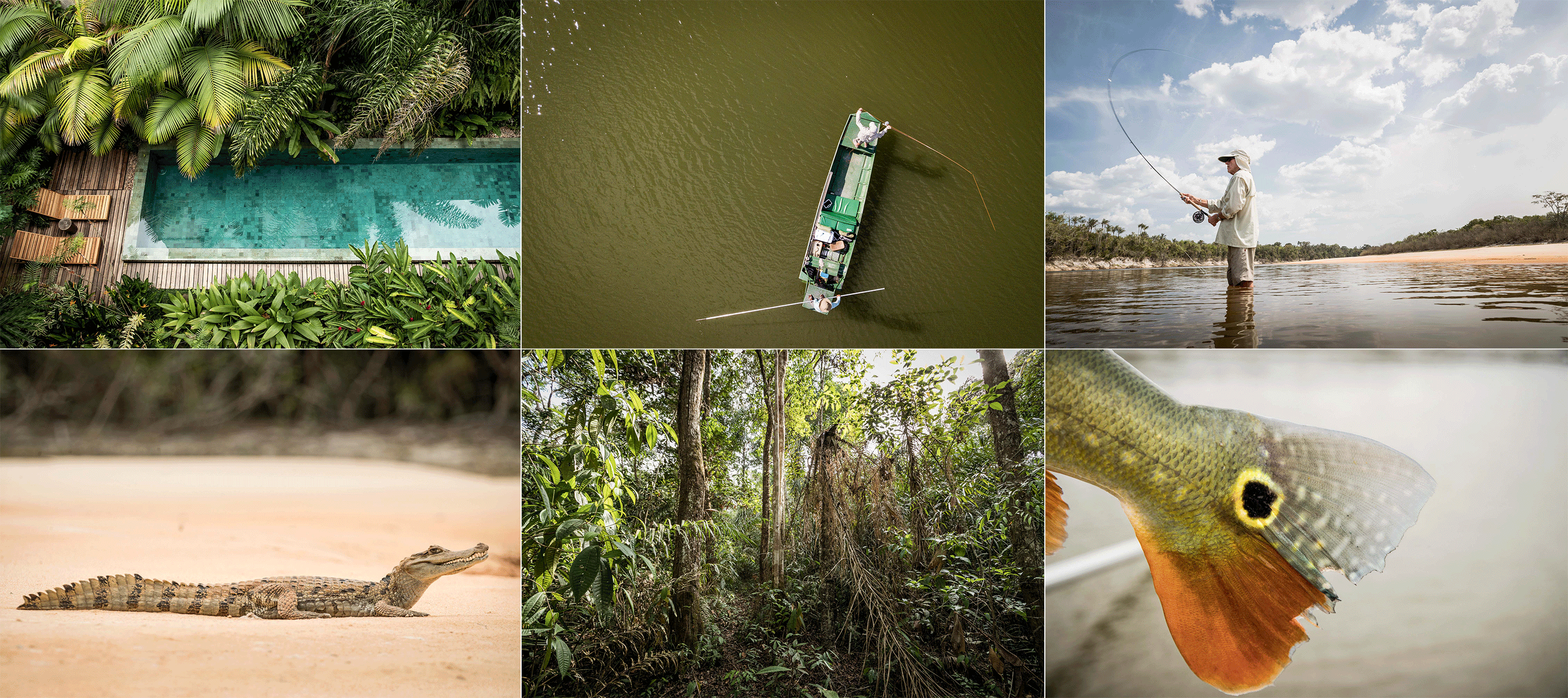

Clockwise from top left: The pool at Hotel Amazonia in Manaus, Brazil, the jumping-off point for Agua Boa Amazon Lodge; angler and guide in one of the lodge’s boats; the author wades into the river for a cast; the tail of a butterfly peacock bass; the dense jungle; a caiman lounges on a sandbar.

You can reach a certain age at which there are only two categories of fishing trips worth carrying you away from your pipe and slippers: those on which the fishing itself is so good that you couldn’t care less about where you are doing it, and those on which the where you are doing it is so stimulating and new that the fishing itself happily takes a backseat to the adventure of being there.

The ideal, of course, as rare as it is unforgettable, is a trip that marries the two categories into one of adventure and discovery on which the fishing happens to be superb—exactly like the jaunt my daughter, Greta; her husband, Michael; a group of our friends; and I were lucky enough to take last spring to the Brazilian Amazon.

Photo: Eric Kiel

A capuchin monkey.

None of us were in any doubt that it would relentlessly be a fishing trip, since the pretrip literature made it clear that our lodge offered scant other options. And after flying in two chartered Caravans 350 miles north of Manaus, Brazil, over an unbroken green sea of jungle canopy, with no more emergency landing possibilities than the mid-Pacific, to forty-eight miles north of the equator, just short of Venezuela to the northwest and Guiana to the northeast, in one of the Amazon basin’s last surviving tracts of uncut and all-but-uninhabited rain forest, none of us could doubt that it would also be an adventure.

Photo: Eric Kiel

A butterfly peacock bass at boat-side; fly rods and reels stand ready for the day’s action.

It is the last week of March. Thirteen of us, eight men and five women, step out of the Caravans into a midmorning’s hammering heat, and there to greet us as if conjured up are a young couple named Suzanne and John who are proffering trays of cold caipirinhas, the refreshing and addictive Brazilian rum drink. I say a pox on anyone who holds that adventure must go without creature comforts, and I am not the only one in our group relieved by this first hint that Agua Boa Amazon Lodge is in agreement.

Photo: Eric Kiel

The pool at Agua Boa.

The lodge appears as conjured as the drink bearers. Carved out of a patch of jungle overlooking the Agua Boa River are six red-roofed stucco guest bungalows, a main lodge building, staff housing, a generator shack…a swimming pool with an open-air bar at one end?! One rubs one’s eyes. And then shakes hands with Carlos Azevedo, fifty-three, the affable and—as we are to learn throughout the week—astonishingly capable lodge manager.

Built by a doctor from Manaus in 2001, and now owned by a Brit with the swashbuckling name of Lance Ranger, the lodge is eighty air miles from the nearest town and fifty from the nearest habitation, a village of Yanomami Indians. It controls over one hundred miles of the Agua Boa River, and that land backs up to an enormous national wildlife reserve. The word remote doesn’t begin to cover it.

Photo: Eric Kiel

The lodge’s general manager, Carlos Azevedo, surveys the river.

After downing our caipirinhas, we follow Carlos into the main lodge building, which houses a large dining room, a living room and bar with satellite TV, and a game room offering Ping-Pong, snooker, and darts. There are good books in the library and wireless Internet. There is daily laundry service. And there is quite good food, we discover over a hearty breakfast served by Suzanne and John. When we repair after breakfast to our bungalows to unpack and rig up for fishing, we find that they too are all one could wish for—each with a large front and back porch, air-conditioning, hot and cold running water, flushing toilets, and plenty of storage.

Impressive, you say, but how could I keep up with my golf game? Well, even there the resourceful Carlos has you covered, with a good collection of irons and a three-hole course in front of the lodge complete with flags and cups. In the bloody jungle! As I have learned over the years, any dolt can run a fishing lodge, but to run one as well as Agua Boa Amazon Lodge is run, particularly given where it is, requires not only tireless work but also an osprey’s eye for detail. While we rig up our fly rods, Carlos wanders from porch to porch, agreeably checking knots and tying on his recommended flies. Looking disapprovingly at the nine-foot, twenty-pound leader I have just looped onto an eight-weight floating line, he says, “Do you mind if I change that leader?” “No. But why?” I ask. “You’ll find out as soon as you hook your first big peacock bass,” he says, replacing the leader with three feet of hawser-like forty-pound mono. It was a detail I came to be grateful for.

Photo: Eric Kiel

A guest bungalow.

Leading us down to the river to meet the lodge’s six guides, whom he trained, Carlos assures himself that each of our twelve anglers, and the photographer Eric Kiel, has with her or him sunblock and sunglasses, and has packed a box lunch from the buffet set up in the dining room after breakfast. He introduces us to our guides. He explains the layout of the six eighteen-foot aluminum skiffs, each fitted out with a poling platform and a forty-horsepower jet outboard. Then he stands with his arms folded on his chest and watches the boats idle away from the dock, three headed upriver and three down, wearing the satisfied grin of a man accustomed to covering all his bases.

There are two types of rivers in the Amazon basin—whitewater ones, which carry pale but nutrient-rich sediments from their origins in the Andes; and blackwater rivers, whose acidic currents flow from tannic lowlands. About 160 miles long from its headwaters in those lowlands to its confluence with the Branco, a major tributary of the Amazon, the blackwater Agua Boa varies in color from that of overbrewed tea in its deeper runs and pools to a clear amber in the shallows, where it flows over sandbars as white as any in Destin, Florida.

The lodge fishes around sixty miles of the Agua Boa, with approximately half that distance upriver from the lodge and half downriver. Carlos has divided each of those thirty-mile stretches into three beats—the closest only a five- to ten-minute run from the lodge, the most distant ones over an hour and a half away—so that in a normal six-fishing-day week, a pair of anglers never fishes the same beat twice, or with the same guide, since each guide is assigned for the week to a particular beat. The system is thoughtfully designed to avoid the ennui of repetition. But because the river is so incredibly complex, endlessly shaping itself into great serpentine coils and oxbows, forming little backwater lagoons and lakes and offering thousands of fishy-looking banks, flats, and pockets, I could have fished the same beat all week, without becoming bored or even knowing I was not someplace else.

Photo: Eric Kiel

A great black hawk.

The fact is, I could have not fished all week without becoming bored, so intent was I in pigging out at the visual groaning board of abundance and variety of biomass that is the Amazon basin seen from a boat. The lodge’s stretch of the Agua Boa runs through savannas and riverine rain forest. That rain forest has never been lumbered or market hunted, and is inhabited only by bands of indigenous natives. It is so utterly, majestically pristine and throbbing with primordial fecundity that simply passing through it on the river tends to produce in an observer the sort of mildly stunned, reverential awe engendered by the interiors of great cathedrals.

Rearing from the understory are thin-trunked bacaba and Tucuma palm trees, rubber trees, and Brazil nut trees; and towering above them are the great-crowned canopy trees, like the epiphyte-laden ceibas, with vertical ridges or buttresses descending from their lower trunks in an earth-gripping spread. And all that verdancy is thronged with life. Over the week our group saw emerging from it howler and capuchin monkeys, marsh deer, collared peccaries, tapirs, and capybaras; a harpy eagle, rufous hawks, parrots, parakeets, and macaws. In and on the water daily we saw otters, pink river dolphins, assassin-eyed caimans (crocodile-like creatures) up to fifteen feet, a prehistoric, foul-smelling mata-mata turtle, as well as an Audubon anthology of birdlife. It was the youngest member of our group, Stew Dansby, who expressed what all of us felt increasingly as the week went on: that each day here was an incomparable river-borne wildlife safari, with fishing thrown in as a bonus. Albeit a munificent bonus.

Photo: Eric Kiel

The flank of a spotted peacock bass.

There are over three thousand species of fish in the Amazon River system, around ten times that in all of Europe, making it the richest ichthyological system on earth. Members of our group caught twelve of those species (plus one small caiman), nine of which I had never before seen or heard about in a long life of hoofing around the globe in piscine pursuit. Among their sonorous names were pacu, jacunda, bicuda, parava, and arowana. We also caught—and ate with relish one night at the lodge—piranha. But mostly what we caught was what we had come all that way to catch: the cage fighter of freshwater fish, the tucunaré, or peacock bass. And I am neither bragging nor exaggerating when I tell you that we caught close to if not over a thousand of them.

Officially not a bass at all but a cichlid (a family of fish known as “mouthbrooders” for the female’s practice of holding her fry in her mouth until they are big enough to fend for themselves), the peacock is a blond, incautious, predatory, and bullying creature that put some of our group in mind of a certain U.S. political figure. It comes in three varieties in the Agua Boa, the butterfly, the spotted, and the temensis. The last of these grows the largest (the world record is twenty-nine pounds) and fights like a cornered wolverine. A seventeen-pounder, our biggest of the week, took a member of our party well accustomed to feisty fish twenty minutes to bring to the boat—on the aforementioned forty-pound-test leader!

All three varieties of peacock bass are as extraordinarily beautiful to study as they are exciting to catch, but the butterfly is truly eye-popping, with its bright red eyes, the highway-cone orange of its pectoral and pelvic fins and a patch beneath its gills, the neon green gold of its flanks shading to olive on the back, and on those flanks and tail ornate black circles like Japanese calligraphy.

The Agua Boa is the sole river in Brazil to allow only fly fishing with single barbless hooks, and fishing from the lodge is exclusively catch and release. Those facts no doubt largely account for why the fishing there has remained so consistently good for seventeen years. So good that many of the lodge’s clients return year after year, including one eighty-nine-year-old hearty who has come for a two-week stay every year for the past fifteen. So good that Stew Dansby, who had never cast a fly rod before our trip, had a fifty-fish day. So good that, if given the ideal water levels we had, two competent and energetic anglers fishing the lodge’s entire long day from 7:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. could reasonably expect to release two hundred to three hundred peacocks a week (as well as a dizzying variety of other fish), most of them between two and five pounds, with perhaps fifty or sixty between six and ten pounds, and a dozen or so over ten and up to twenty pounds.

Photo: Eric Kiel

Poppers and streamers.

Most of the fishing is done by casting big streamers or poppers from the boat (or, for the nonskittish, by wading the sandbars) to holding pockets along the banks, and, with sinking lines, into deep pools and channels. But if you visit the lodge when the water is low and clear and the peacocks are on their beds, you can sight fish for them—a rare opportunity anywhere in the Amazon and one of the most thrilling in all of angling.

It is the last day of our trip and the last day of the lodge’s season. My great Argentine pals Buby Calvo and Maita Barrenechea have invited me to fish with them, making for a crowded but congenial boat. Carlos sees us off at the dock a little after 7:00 a.m., and we run for half an hour, scattering herons and egrets, to a flat that our guide, Caboclo, has been saving, knowing that sight fishing is our entire agenda for today.

The flat is in a grassy, pond-like lagoon, perhaps half a mile across and entered via a narrow opening off the river. It is a magical place with giant water lilies skirting its banks and red-collared jabiru storks and roseate spoonbills wading its shallows, its water clear and three to four feet deep.

Photo: Eric Kiel

A pair of roseate spoonbills feed in the shallows of the Agua Boa.

With Buby in the bow, Caboclo poles us in silent zigzags across the lagoon’s still surface, and as the sun climbs higher, we begin to see beds—two- to three-foot-wide white patches showing clearly against the tan bottom—and on each one, one and sometimes two peacock bass between six and fifteen pounds. Sometimes they take on the first cast over the bed, sometimes on the twentieth, and sometimes not at all; sometimes on a fast strip, sometimes on a slow one, and sometimes on stopping the fly in the middle of the bed. It is fishing by feel, by finding the right intuitive entry, as narrow as that into the lagoon, into the responsiveness of the fish. And it is riveting: fishing impossible not to holler over. While Maita imperturbably reads an Argentine potboiler, Buby and I holler and hook fifteen to twenty peacocks in the lagoon, each absolutely murdering the fly on the take and fighting far above its weight.

One of those peacocks is hooked in the gills and bleeding, and the lodge allows you to kill such fish. We do, and Caboclo cooks it for our lunch on a grill of green branches that he fabricates in less than five minutes with his machete while Maita, Buby, and I lounge in the boat in the shade of the bank, drinking tart Brazilian beers.

Photo: Eric Kiel

A peacock bass hooked in the gills becomes lunch on a bed of green sticks and fire.

Every great trip for me has a defining experience residing in it, and in my memory of it, like a pearl in an oyster. There were many memorable experiences on this trip: the hour-long nature hike through the jungle behind the lodge; draining off the stored heat of the day, caipirinha in hand, in the chest-deep pool after nine hours of fishing; the cool gray early mornings and evenings with pacu rising on the river and the air full of swifts; the fine boisterous dinners each night with good food, good friends, and Suzanne and John keeping the wineglasses full.

But the pearl for me was this:

After we finish picking all the sweet white meat off the peacock’s bones with our fingers, I throw part of the skeleton into the river, and a medium-size caiman swims up to within ten feet of the boat and loudly eats it. Then it lies there in the water with just its knobby head showing and its black vertical pupils fixed, it seems, on me—as if I have personally invited him to join our food chain.

Some rain-forest scientists have been known to take a dump in the jungle just to sit and observe with aesthetic pleasure the astonishingly short length of time it takes for over fifty species of dung beetles to converge on the scat and devour it. “Dung gazing,” they call it. Yes, well, as Isaiah noted, all flesh is grass; and nowhere is that truth more vividly demonstrated than in the Amazon, where every organism is caught up in a raucous 24/7 orgy of snatching life from death: At certain times you can almost hear the steady clicking hum of millions of beings feasting on millions of others. Over the week, I have come to realize that what is so moving to me about the place is stately beauty barely concealing mayhem in all that raw, immeasurable fertility—a palimpsest of infinitely intricate pattern and design laid over utter mercilessness, perhaps like that of the cosmos itself, in fifty shades of green.

Photo: Eric Kiel

Working the river for a strike.

But I came to that realization as an observer in a boat with fly rod or beer can (sometimes both) in hand: a mere dung gazer. Now, staring at my reptilian friend, I have a sudden, overwhelming urge to paint myself into the picture; to be, if only for a moment, on the inside of the Amazon looking out. So I slide into the Agua Boa River, among its piranhas; its freshwater stingrays; its myriad minnows that nibble on your skin, feeling like little jolts of electricity; its tiny fish called candiru, which are said to swim up your urine stream and lodge horribly in your urethra. I slip into the inscrutable pattern and design of that black water and toss the last of the peacock bass bones to my brother caiman. Then we swim around together for a while, contentedly digesting.

“I am a meat-hungry buzzard!” was the cry of the Yanomami Indians when they went on raids into foreign territory. I feel like shouting it out.