Arts & Culture

Step Into Nigel Parry’s Sensory-Rich Southern Landscapes

Mysterious, hazy, awash with color—Parry’s latest show, Portraits of Landscape, captures the momentary magic of South Carolina waterways on film

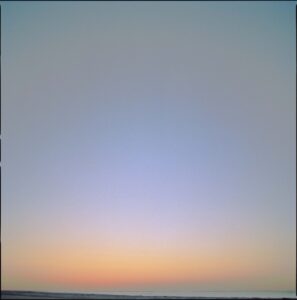

Photo: Nigel Parry

Sunrise over the beach at Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina.

Nigel Parry turned to nature—and his Hasselblad camera, bike, and heavy-duty DEET—when the pandemic struck in 2021. The photographer, whose work focuses on expressive portraits of high-profile actors, politicians, and artists for publications like Garden & Gun, TIME, Vogue, and New York Magazine, had to transform his creative practice. “When COVID-19 hit, my workload went from fifty shoots a year to zero,” says Parry, who splits his time between Charleston, South Carolina, and Upstate New York. “I thought, if I can’t photograph people, then let’s go back to my roots. When I was a kid, I shot landscapes all the time.”

Photo: Nigel Parry

From left: Parry's portrait of poet Allen Ginsberg; Eddie Van Halen and George Clooney.

Originally from London, Parry was instantly charmed by the Lowcountry when he first arrived for a photography project in 1995. “I remember being down there and feeling this incredible sense of peace with those lowlands,” he says. “It’s a whole different pace of life.” From May 5 to June 11, the Corrigan Gallery in Charleston will host his first landscape-centric show, Portraits of Landscape, featuring images from both of his homeplaces shot entirely on film. The exhibition will also include some of Parry’s portraits from the course of his career.

Photo: Nigel Parry

These images both show the same location on Lake Placid but at different times of day.

For Portraits of Landscape, Parry chased the Holy City’s tranquil aura, scouting out waterways in his car before biking out with a thirty-pound backpack laden with old film cameras. He set up his Hasselblad—a heavy, iconic, medium-format Swedish camera—at Harelston Village’s Colonial Lake, the beach at Sullivan’s Island, and north toward the Santee River. The Hasselblad and rolls of grainy Portra 400 couldn’t have been more of a departure from his portrait work, where digital photography produces “tack-sharp” hyperacuity. “Landscapes lended to the organic nature of film,” he says.

The medium’s soft diffusions of color, rich pointillistic texture, and processing irregularities yielded dream-like, abstract photos that resemble meditative Mark Rothko paintings. “The imperfections in film are what make it more ‘real,’” Parry says. “Our eyeballs are not focused all the time. They only focus on one tiny area, and the rest becomes slightly superfluous.”

Photo: Nigel Parry

Morning mist rises over Colonial Lake; the same location at another time of day.

Like a giant Rothko or dotted George Seurat painting, Parry’s work reveals more the longer you linger with it, stepping forward to hone in on a tiny detail or backwards to see the larger picture. His silvery image of Colonial Lake may initially look like a fuzzy gradient, for example, but the midsection of the landscape hides a thin thread of land—a pedestrian walkway that encircles the large pool in downtown Charleston. As if on a piece of paper folded in half, puffs of hazy palm trees mirror each other across the horizon line, and a glint of sunlight catches the pool near the bottom. A beautiful anomaly of cool-toned blue leaks in from the left and right edges. Like French Impressionists, Parry also explores the momentary effects of light, showcasing the same landscapes at different times of day, resulting in dramatically different colors, exemplified by his rosy second shot of Colonial Lake.

Photo: Nigel Parry

Above the Santee River, shot from a fire watch tower; grass around the river.

Or, take Parry’s image above the Santee River, where sunlight glistens like stars over the rippling dark blue surface. Zoom in, and the photo shows the diversity of color in light: bright red, pale green, and aqua blue. Some of the sunlight appears as irregular smatterings of white dots with rings of red and blue—an irregular quality that, if shot digitally, would not likely appear. “I emphasize the imperfections and the strange color aberrations that I see on the initial scan,” Parry says. “There’s an element of surprise with the unexpected nature of film.”

Gabriela Gomez-Misserian, Garden & Gun’s digital producer, joined the magazine in 2021 after studying English and studio art in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. She is an oil painter and gardener, often uniting her interests to write about creatives—whether artists, naturalists, designers, or curators—across the South. Gabriela paints and lives in downtown Charleston with her golden retriever rescue, Clementine.