Travel

The Birdman of Honduras

Lloyd Davidson has always been prone to wanderlust and wild ideas, but even those who know the Tennessee native could never have predicted he’d be the best hope to save the scarlet macaw

Kyle Johnson

By the time he was in the ninth grade, Lloyd Davidson knew he wanted no ordinary life. For starters, he asked his parents if he could attend McCallie School, a private boarding academy in Chattanooga—a military school at the time—pretty much for the fun of it. The travel bug bit hard in the summer of 1959, when he signed on for a free-diving camp in Tobago, which back then might as well have been Mars. “That summer screwed me for life,” Davidson says, in a low, gravelly Knoxville drawl. Davidson is a Steve McQueen look-alike, lanky and fit for a fifty-year-old, all the more impressive since he just turned seventy. “I can trace every abnormal thing I’ve ever done to that experience.”

So it wasn’t much of a surprise when Davidson took a year off from prestigious Davidson College to sail around the world after answering an advertisement in the back of National Geographic. And no one was shocked, either, when he joined the Coast Guard and spent half of his four-year stint as a diving officer on a polar icebreaker. That was just Lloyd being Lloyd. Same for a second round-the-world sailing venture, after which he wound up in Beaufort, North Carolina, working at the University of North Carolina Marine Laboratory and boning up for graduate-school exams. That didn’t last. He spent the next twelve years as a commercial fisherman off North Carolina’s Cape Lookout and Cape Hatteras. In 1984 Davidson caught a 2,080-pound great white shark, hauled it to the North Carolina State Fair, and charged admission until it started stinking so badly he decided it was time to leave. Even when Davidson moved to Roatán in 1986, a small island off the coast of Honduras, to start a fish export business from scratch, supplying snapper and grouper to East Coast restaurants—a company he ran until drug lords shouldered him aside—his closest friends were hardly surprised.

But in his many wild dreams, Davidson could not have imagined this.

“It’s been so surreal,” he says, standing under ancient Mayan temple ruins, holding a plastic tray of leftover tortillas, papaya, dog food, and toucan chow. “Saving the national bird of Honduras. Really?”

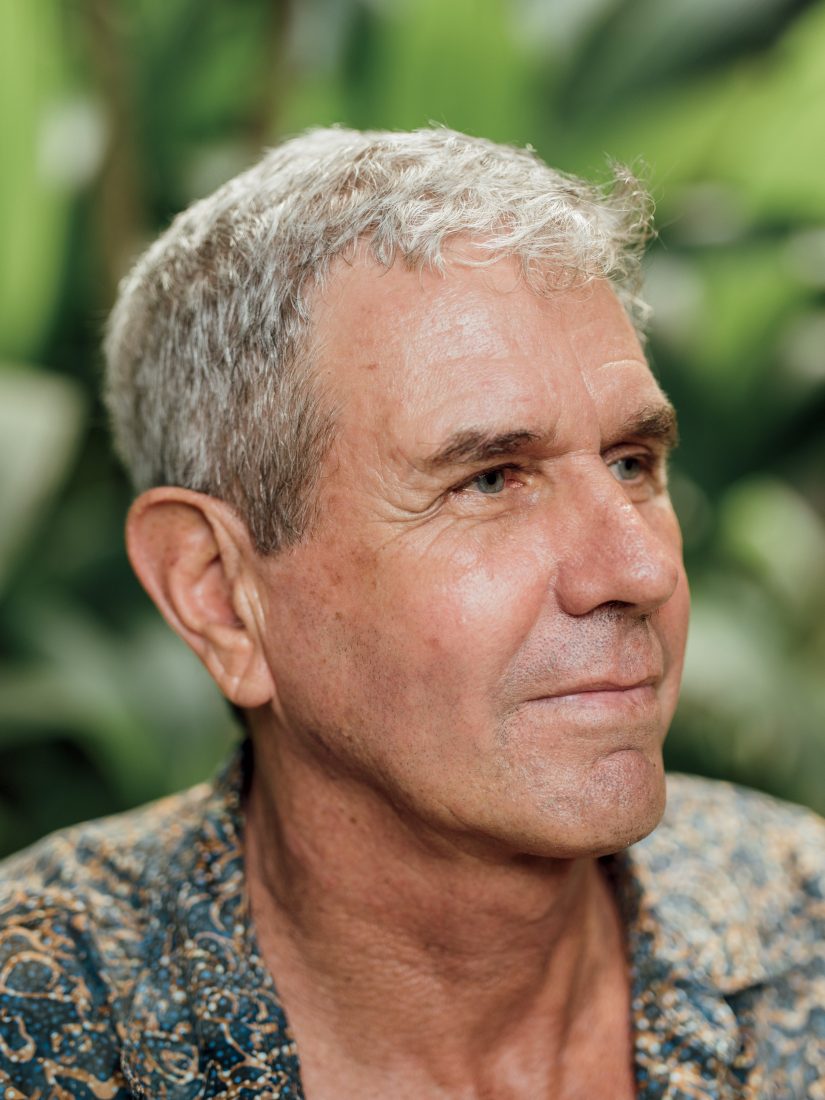

Kyle Johnson

Davidson at Macaw Mountain.

The scarlet macaw is one of the world’s largest parrots, a nearly three-foot-long, overly exuberant, wildly colored embodiment of pirate ships, Jimmy Buffett, and tropical paradise. The birds were once found from Mexico to Peru, but populations have been exterminated across vast swaths of their range. They’re gone from most of Mexico and nearly extinct in El Salvador, and they exist in only isolated pockets throughout much of Central America. Guatemala and Belize share a few hundred. Costa Rica has about a thousand.

In Honduras, which designated the scarlet macaw its national bird nearly twenty-five years ago, the parrots are found in the wild only on the far eastern border with Nicaragua, where the tangled million-acre-plus La Mosquitia wilderness shelters a few indigenous villages and perhaps the most active drug-smuggling routes in all of Central America. Poaching for wild scarlet macaw chicks there—the adults can bring two thousand dollars in the illegal pet trade in the United States—is rampant.

Whatever hope there is for restoring the birds to the rest of Honduras is found in a lush, manicured nine-acre compound of mature forest just outside of Copán Ruinas, a cobblestoned village high in the mountains on the border of Guatemala. His Macaw Mountain Bird Park & Nature Reserve, which Davidson founded fifteen years ago, is a sanctuary for abandoned pet macaws and other native parrots and parakeets. Most have been so long in captivity or so long abused, or both, that they could never make it in the wild. Others were injured and then tossed aside by poachers. But in addition to running the park as a rescue, public education, and tourism enterprise, Davidson and his staff are breeding scarlet macaws and releasing the young into a valley marked by some of the finest Mayan ruins in all of Central America. When he arrived in Copán, about fifteen sick and flightless half-feral macaws rambled around the entrance to the Copán ruins, living off of chips and leftover tortillas tossed by visitors. But in the last four years, those birds have been nursed back to health. More than fifteen other scarlet macaws have been captive-bred. Today, nearly three dozen scarlet macaws fly wild in the Copán valley, and Davidson is now working to develop other release sites in Honduras, including the Lodge at Pico Bonito on the border of the second-largest national park in the country, and a secure island off the coast where twenty-two scarlet macaws were released and have begun to raise young.

“Five years ago, had you asked me if this kind of project would work, I would have told you that you’d lost your mind,” says Dr. James Gilardi, executive director of the World Parrot Trust, which partnered with Macaw Mountain to bring scientific process to what Davidson admits can be his penchant for wild schemes. “But the fact is, while we pointy-headed scientists turn circles trying to figure out what to do, this commercial fisherman, this Southern good ol’ boy, comes down here and gets the work done.”

It’s difficult to pin down when it all really started. Davidson first visited Roatán when his old diving buddies were trying to build a small resort business there and asked for help. “I got my Coast Guard discharge papers,” he says, “dumped my uniforms in a Goodwill box, and forty-eight hours later I was in Roatán.” Not long after moving down permanently to start his Flying Fish export operation, he adopted a pair of scarlet macaws left in the lurch when a Roatán resort went belly up. With an expat friend, Davidson began taking in macaws from neighbors and locals disenchanted with a spaniel-size bird that can cop a surly attitude and live for more than seventy-five years in a living-room cage. “People get to paradise,” he quips, “and the first thing they think they have to have is a parrot. But within a couple of years they’ve had it with the bird or with paradise itself. Either way, we’d end up with the birds.”

This accidental aviary grew to nearly forty birds when his friend moved off the island in 1994, and Davidson inherited the whole shebang. Still the birds kept coming—a Noah’s ark of scarlet and great green macaws, mostly, but also red-throated parrots, various and sundry parakeets, the odd tropical owl. He became known as the Birdman of Roatán. He built a small bird park that catered to island divers and the occasional tourist. His bird numbers more than doubled.

Birdman of Roatán. He built a small bird park that catered to island divers and the occasional tourist. His bird numbers more than doubled.

Roatán was changing, too. Once a funky backwater, the island had become a posh diving destination and a favorite of cruise ships. Davidson’s day job was no walk in the park, either. Through the mid-1990s the fishing industry was being squeezed by drug traffickers who wanted a piece of the action. Davidson wasn’t stupid; it was time to go. In 2000 he bought Finca Miramundo, a coffee plantation in the stunning mountains above Copán, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that contains some of the finest Mayan ruins in all of Central America. He locked down land for his menagerie. In the summer of 2002, he left Roatán for good. He chartered a twin-engine airplane, removed the seats, and filled the passenger bay with birdcages. When the plane settled down on a dirt strip in Guatemala, close to the Honduran border, two things weighed heavily on his mind: This coffee business had better take off pronto. And he sure hoped he’d made the right decision for his birds. After all, there were ninety of them looking out the plane’s passenger windows.

Honduras has its baggage, there’s no denying that. Its reputation for crime is well documented. Per capita income is $2,280; in Central America, only its neighbor Nicaragua is poorer. The 2009 coup that ousted President Manuel Zelaya sent the national economy—and tourism especially—into a tailspin. It has never fully recovered, despite improving crime statistics, despite a growing reputation for ecotourism that is drawing larger and larger numbers of Europeans, despite the safety of vacation destinations such as Roatán and Copán.

For Davidson, it’s as much like the South as anyplace he’s been. “Squint your eyes and don’t look at the palm trees,” he says, “and it’s pretty much the same setup as East Tennessee.” Creeks tumble through heavily forested valleys, the skyline crenellated with green mountains. “I was here maybe two years when I looked up one day and said, wait a minute. This is like home. I even dammed a swimming hole in the creek, because that’s what we rednecks do.”

RELATED: A VISITOR’S GUIDE TO COPÁN

But it’s as much about attitude as geography. The horses tied to the rough railings on the outskirts of town—Davidson remembers that from rural East Tennessee. Kids still swim in the rivers here, too. Generations mix, and family gatherings matter. Davidson even bought the land for the bird park on a handshake deal. The landowner was a tall man in a cowboy hat, “the kind who looked you straight in the eye,” he recalls. When Davidson asked for a contract, the Copáneco stuck out his hand. “At the time I thought I was the craziest gringo in Honduras,” Davidson says, “but I told him: ‘Where I’m from, we still do things like this.’”

Honduras is also a place “where you can get shit done,” Davidson says, his language salted with a waterman’s patois, “as long as you don’t piss too many people off or do anything that really freaks out the authorities.” Within a month of kicking off construction of the macaw restoration effort, he had two government agencies, a nonprofit NGO, and a private enterprise signed on to support the bird park.

Now the bird park has evolved into a can’t-miss Copán attraction. When I visit with my daughter, a school group had toured the park earlier in the day, but we share the compound with just a few local families and a handful of tourists. Our guided walking tour takes about an hour and a half, and wanders along carefully built boardwalks that tunnel under natural forest—cedars and mahoganies and red-barked jobo trees whose branches sag under orchids and bromeliads. Around each walkway bend lies a soaring aviary, constructed of black netting, mostly, and housing an astonishing array of tropical birds. There are scarlet macaws, of course, but also orange-fronted and red-throated parakeets, red-lored Amazon parrots, keel-billed toucans, and mottled owls. Wild motmots call along the creek that flows through the property. Staff occasionally hear ferruginous owls calling overhead—four tiny young were recently released from a captive pair. Cinnamon hummingbirds flit through dense gardens of hyacinth and wild ginger.

Kyle Johnson

Hand feeding a rescued three-month old macaw.

All told, Macaw Mountain is home to about 225 rescued birds—it just received 31 birds confiscated by the Honduran government in a wildlife sting—and the operation is almost entirely supported by ticket sales and cups of coffee and souvenirs. The bill for seeds, fruits, toucan chow, and live chickens for the hawks and owls runs nearly two grand a month. Davidson employs thirteen people full-time and figures it costs $8,000 to $9,000 a month to run the bird park. While the macaw release project is in part supported by the World Parrot Trust, Hugo Boss, the Honduran Institute of Anthropology and History, and the Copán Association, Davidson needs the bird park to subsidize the scientific endeavors, and often, it’s his coffee farm that fills the gap.

At the end of our tour we find Davidson at a picnic table at the bird park’s outdoor restaurant, where he holds a tiny scarlet macaw chick, rubbery and quivering. Three days earlier, the bird had been abandoned by its parents at the Copán ruins. It was the third egg to hatch, and parrots will often kick baby number three out of a nest to shunt more resources to the first two young. Typically, a third chick has about a 5 percent chance of survival, Davidson says, “but this bird will have a different future.” If it survives, it could be released into the wild. He places the chick back into a plastic kitchen tub, swaddled in a snack-bar hand towel.

As word leaked out about Davidson’s plan for the bird park, not everyone was in support. Some scientists worried that locals had no clue how to care for tropical birds. “People were literally yelling at me that this was the worst idea ever,” Davidson admits. Even today, some visitors “expect a roadside attraction, like the old bears in Gatlinburg,” he says. “A bird park in Honduras? Well, that’s got to be a horror show. But they come anyway, and they leave just blown away. Really, there’s just a startling amount of cooperation, from every strata of society.”

Now people are calling the park to report seeing macaws. The day we arrived, Davidson picked up a toucan from San Pedro Sula—a taxi driver saw the bird and arranged to meet Davidson in front of a local barber shop. Not long ago, neighbors ratted out a man keeping a macaw in his yard high in the mountains five miles outside of town.

“A lot of purists would screw around and pick this thing apart until the last macaw was gone out of Honduras,” Davidson says. “This is not a peer-reviewed project run by a bunch of PhDs, but if we can pull this off with a minimum of BS and cost, it will work in a lot of places. These may not be totally wild birds here, but in two or three generations, the great-grandchildren of these birds will be nesting in the wild in places we don’t even know about. We’re always moving toward that. To be honest, though, I never intended for it to be this big or complicated. I’m just sort of slow to give up on stuff. So for whatever reason I just said: Okay. This is my problem.”

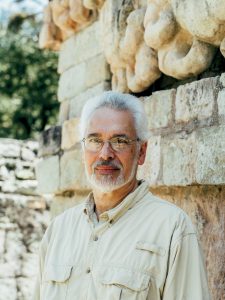

Kyle Johnson

Archaeologist Ricardo Agurcia at the ruins.

“Do you see them? Here are the claws. The eyes.” Professor Ricardo Agurcia uses a small flashlight as a pointer, moving the shaft of light across a relief of carved stone. “And there: the wings with their overarching feathers.” We are deep inside the soaring Temple 16, a 100-foot-tall pyramid on the Copán Acropolis, beyond a locked metal door and down a dark corridor of excavated tunnel. Like other Mayan temples, Temple 16 was constructed atop earlier buildings. Dozens of holy structures lie within the exterior walls, including a nearly intact temple named Rosalila, which Agurcia discovered in 1989.

Agurcia is one of Honduras’s most renowned archaeologists, a scholar whose investigative work on Mayan ruins is paired with a heart for educational outreach. With the flashlight he points out the face of the sun-king K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’; the first king of Copán slowly emerges under the feathers of a quetzal and a macaw—a large aquiline nose, massive jade earrings—as Agurcia paints the entombed temple facade with the flashlight.

Few in Copán have as cultivated a sense of chronology as Agurcia, and the grasp of how entwined macaws are with the region’s cultural geography. At Copán, he says, the Maya revered macaws. There are perhaps more bird sculptures at Copán than at any known Mayan site, and there are more macaws displayed at Copán than any other bird. Seven macaws adorn the facade of the Rosalila temple. I count seven carved macaw sculptures guarding the ancient ball court outside. The towering stelae around the ancient plaza carry more carvings of macaws.

But those are all ancient renderings, stylized and oversize, lifeless but for the ancient meanings they bring to stone. Outside Temple 16, Agurcia sits on a bench to consider the contemporary story of the bird.

“I can tell you this,” he says. “I never would have thought I would see macaws flying here. Not in my lifetime. It is astonishing what Lloyd has done—all the more so for how quickly he has brought all this together. The bird park is a world-class destination, and it is really jaw-dropping how successful the release project has been, and how completely it’s been accepted by the local Copánecos.”

Indeed, Davidson’s own integration into the cultural and civic life of Copán seems to be nearly complete. His bird park is touted as a scientific and tourism success. You can buy Café Miramundo at hotels and gift shops throughout the city. He lives in a restored adobe home halfway up a hillside two blocks from the Copán central plaza. Even the town strays find Davidson just this side of irresistible. He feeds untold numbers of street dogs, many of which know him by sight and recognize his battered Toyota Land Cruiser by sound. After a lifetime of roaming, he has found the one thing he was never looking for: home.

Kyle Johnson

Wild scarlet macaws soar toward the tree line in Copán.

It’s all too easy to romanticize his Mesoamerican refuge. Life for Davidson has its moments of disquietude, its aggravations, and its piles of bird poop. But it does appear that he’s found a piece of the South that makes sense to him, even if it’s fifteen hundred miles from Knoxville. He’s fashioned a genuine and meaningful career out of the sorts of umbrella-drink dreams we all have when we just want to screw it all and start over in some tropical paradise. Adopt a bunch of skinny dogs. Maybe even open up a bird park.

Once, I asked Davidson if he wants to return to the United States, and he shook his head. When he travels now, after just a couple of days away, he feels boxed in and ready to return. The bird park needs constant attention. The coffee finca is still rebounding after a coffee rust outbreak in 2013. The macaw release program could triple in size and scope in less than a year. His roots are deep, sunk into soil that finally tamed a wandering spirit.

On my last morning with Davidson, we meet back at the ruins. On most mornings, he’s there by 7:00 a.m. to fill the bird feeders that now line La Gran Plaza, a wide boulevard that gives way to the temple grounds, one of the largest ball courts in the Mayan world, the hieroglyphic stairway with 1,250 carved stone steps. Wearing river sandals and cargo shorts, he shovels bird grub into feeding troughs made from PVC pipe. A single scarlet macaw soars overhead, impossibly colored, screeching and squawking. It’s joined by a pair, then five more, then another eight. Davidson looks up as they fly over in a squadron that circles the Mayan temples, the carved monolithic stelae, the round sacrificial stone carved with grooves to channel blood to the ground. The birds circle and then vanish through the trees, headed to the far side of the park and out of sight and then to who knows where. The next valley over? Guatemala?

Davidson empties the food tray, cranes his neck, and watches the pageant. To no one in particular, and most likely to himself, he looks up at the birds and mutters: “That’s pretty wild, huh?”