Sporting

The Ducks of Home

A few classic Southern haunts—and their challenges—call one lifelong waterfowl hunter back season after season

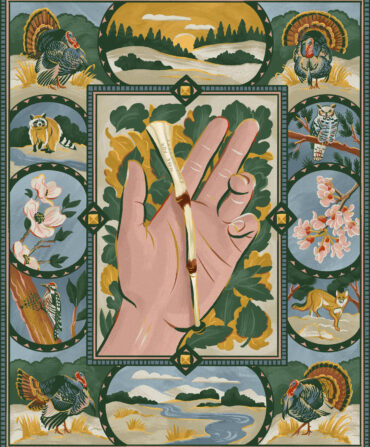

Photo: FREDERICK STIVERS

I. THE HORSE SWAMP

Under the cypress trees, I sit on the remains of an ancient beaver dam, mossy and moldering. My son, Jack, sits on a fallen log. It’s an arrangement we’ve settled into over dozens of duck hunts here. We are far enough apart that we can each safely swing a shotgun, but close enough that I can hand him a venison tenderloin biscuit without making much movement. And we’re close enough to carry on a conversation.

That has turned out to be the most important reason I lease the Horse Swamp. The duck action is irregular here—heck, it can be largely absent—but the gorgeous old beaver pond is just far enough of a drive from the house to make us feel like we’re getting away. We know every stump and creek channel. We have hunkered down under those cypresses and talked our way through Jack’s middle school social angst, high school girlfriends, and college application essays, and most recently, how to navigate his new job and new life in a distant city. We have killed ducks and geese, to be sure. But what we remember most clearly, and why we return so often, is how the Horse Swamp seems to be a place that leads to deep thinking. Our place.

I travel widely to hunt ducks, on treks that can take me to boreal Canada and rocky Maine and the tidal reaches of the Columbia River in Oregon. But most of my hunting occurs in the South, and like most waterfowlers, I suspect, I return to the same places time and again. The Horse Swamp is one of those spots. We named it for the horse pasture we have to cross to get to the water. Even in the dark, those cypress trees form a certain silhouette against the sky that greets us as we push the canoe into the swamp. I see them in my memories, and I see them in my daydreams of Horse Swamp hunts to come.

I’ve long thought that a sense of place is a heart thing, discrete from intellect, but I’ve had to reconsider that position. I recently read about three scientists who shared a 2014 Nobel Prize for their discoveries of specialized brain cells in rats that work together to build mental maps of the spaces they frequent, and store that information for recall whenever they return. In the brain’s hippocampus are so-called “place cells” that support spatial memory. Every time a rat in a maze crossed a familiar spot, these neurons activated. At the same time, in the medial entorhinal cortex adjacent to the hippocampus, what the researchers called “grid cells” activated as well. Information flows between these two brain cell types, and together, the cells form what the Nobel assembly called “an inner GPS in the brain.” Scientists hold that the human brain also most likely contains these cells, and together they allow us to identify places and to sort and organize memories that are tied to specific locations.

The takeaway: When I move into view of those Horse Swamp cypresses, the swelling I feel in my heart has roots deep in my gray, furrowed noggin. Those fuzzy feelings are the by-product of neurons sparking across millions of microscopic synapses in the hippocampus and medial entorhinal cortex. My love for the Horse Swamp is only partly an emotional response. The same goes for my affinities for other Southern duck haunts I frequent. These affections are literally wired into my brain, as much a part of who I am as my struggles with math and my love for collards.

That’s some deep rumination to spring from a morning in a duck swamp. But in a Southern duck blind, there’s often a surplus of time for unencumbered thinking.

Photo: FREDERICK STIVERS

II. NO-NAME CREEK

The ducks know something is not quite right, but they have yet to figure out the game. I angle the paddle so the blade passes under the canoe, pull it past my hip, and then scull it forward silently, never lifting it from the water. The canoe shimmies slightly, and I cringe. The ducks are forty yards away, and that meager movement jostles the bamboo and holly that camouflage the boat, nearly encircling it. Two of the wood ducks raise their heads in an alert pose, feathered crests erect, red eyes searching. I let the canoe drift. Thirty-five yards now, and I hear my heart thumping.

Another few ducks suddenly emerge from behind a fallen tree, swimming quickly. In the bow seat, Jack signals to me with his fingers held behind his back: Three birds, now five. He shifts the shotgun slightly, moving the muzzle toward the birds, and it’s going to happen any split second now, as I turn the bow to give him a clearer shot.

Twenty yards now. Fifteen. Close enough that I can make out the lemon feathers on the drakes’ breasts. They’re almost too close to shoot when the first woodie flushes, and one duck might still have a toe on the water when Jack’s shot sends the birds vaulting for the sky in a detonation of wings and webbed feet and shot raking the surface.

Much as I love to see the sun come up from a duck blind, I may love to paddle a canoe into a flock of ducks a bit more. This particular stream flows through a buddy’s large farm, fed by beaver-dammed tributaries that wind through miles of woods. I like a body of water small enough to shoot all the way across, and kinked up like a scuppernong vine, with each twist and turn revealing new water. It’s like hunting a few dozen places all in one morning.

We wait for a bitter night to freeze swamps and beaver ponds, and push off in the morning in a carefully camouflaged canoe laden with spare clothing, a camp stove, and venison stew. We’ve hunted the creek often enough to know which bends tend to hold the wood ducks and where we might see a goose. We have lunch along the same timbered bluff. It’s a curious blend of the familiar and the unpredictable, for the ducks could be around any bend and tucked into any fallen treetop.

I move the boat as slowly as possible, never faster than the creek’s natural rate of flow, which is far harder and more skillfully demanding than paddling at a normal cadence. To be honest, I’m just as happy in the stern, paddle in hand, while a pal handles the shooting. On these floats, it feels as if I’m moving through two different dimensions: I am flowing through the landscape itself, the timbered bluffs sliding by in slow motion as I move in and out of the shadows of white-barked sycamores, their twisted branches groping over the creek, seeking sunlight. Pileated woodpeckers swoop low in front of the boat. Put a duck in the picture, though, and my focus narrows instantly. I am stalking prey now. Each movement of the paddle is planned and deliberate: Keep the boat pointed straight at the bird, to minimize its profile. Scull the paddle to dampen movement. No matter how many times I’ve paddled this creek, with a duck in view, everything old is new again.

I pull the paddle past my hip, cut the distance to the ducks, and move more deeply into the moment. Deeper, always. And always just a little bit closer.

Photo: FREDERICK STIVERS

III. THE SNAKE ISLAND HUNT

They come from behind us, from the rice field across the levee, a wad of teal that shape-shifts as it moves like an inkblot shot from a cannon.

“Oh, shit! Birds!” Jimmy Robinson hisses. “Don’t move!” he says, and, of course, we all instantly scramble around in the pit blind to cop a look before we freeze into place. The teal boil over the blind so close the rush of wind nearly lifts our hats, and the flock banks hard over the water to skirt the decoys, each bird moving in concert with the others, like a miniature murmuration of starlings. They’re curious but not convinced, so they make another sweep around the flooded field, then turn for the decoys. “This time we take them,” says Jimmy’s father-in-law, Fred Silverstein, the patriarch of the group, with teeth gritted and gray locks peeking out from under his cap like the curled feathers on the back of a mallard.

Then Jimbo Robinson—Jimmy’s son, the one they call “C.E.-Bo” for his take-charge approach—calls the shot, and five of us rise, trying to focus on a single bird in the whirling dervish of ducks that dips, dives, and rockets skyward with the first shotgun report. Four teal fall, and Jimbo sends the dog. “Not a bad showing, fellows,” Silverstein says. “Those ducks weren’t going to land, so it was now or never.”

That kind of calculus is often what it takes to put ducks in the bag down he-ah. We get the smart ducks, Southern hunters like to say. It’s a sheepish defense, a way of compensating for tough days in a blind, but it’s largely true. By the time a tundra-bred canvasback or a pintail from the prairies or a black duck hatched in some dark boreal fen makes it to the South, it has been harried and hammered for hundreds of miles. It has seen every arrangement of decoys and heard every duck call. Southern hunters yearn for a polar vortex or lake-effect snow or a nor’easter to send the ducks down, even as we know that what rides the wind will be the battle-hardened leftovers.

Those are the birds we watch for from the rim of this Arkansas pit blind, a half hour west of Stuttgart, the South’s most acclaimed duck hunting area. It’s a mix of sprawling rice fields and flooded timber, labyrinthed with sloughs and ditches and creeks and rivers, and a duck club seemingly every square mile.

Over the past decade, I’ve fallen in with a memorable crowd in Arkansas. Once a year, for three or four days, I hunt at the Snake Island Duck Club. Housed in an abandoned cinder-block church, off a dirt road flanked by rice fields and timber for miles, it’s a family club, nothing fancy about it, though every square inch of Snake Island has become hallowed ground to me. Jack and I revel in our status as adopted family. A few years ago, we arrived at Snake Island to find that we had our own Christmas stockings hanging from the fireplace mantel with those of the Silverstein and Robinson families. Granted, our stockings were used white athletic socks thumbtacked in place, but that only added to their value.

I love the adventure of hunting new waters, but there is something that feels almost sacred in hunting familiar places time and again. Sacred in the sense that the act of returning requires measures of both hope and faith, and in the sense that there is always an expectation of blessing. And duck blind blessings manifest themselves in many forms. Each sunrise from a blind is like a diamond-tipped stylus traveling the grooves in a vinyl record, translating the twisting flight of a wood duck and the clean smell of mud into music. I’ve seen a lot of Snake Island sunrises, some filled with ducks and some filled with the absence of ducks. But none have been empty.

What is curious, however, is why some flooded fields seem to hold ducks year after year, when an almost exact duplicate just across the ditch or down the road is nearly devoid of birds. I once asked a waterfowl biologist about this. He laughed and said, “You’ll have to ask the ducks.”

But then he offered a thought completely unfounded in science, though one that makes a sort of visceral sense. For centuries, he said, this stretch of Arkansas was a broad mosaic of wet woods and water. Then the land was settled, the forests cut down, and the clearings ditched and leveed. He wondered if the ducks might still be drawn to those places where the long-gone creeks and swamps used to be, gathering in those rice fields that were once flooded timber or a meandering mire.

So, I wonder: If we could look inside their tiny skulls, perhaps we might see place and grid cells firing with the cognitive memories of a thousand generations of ducks as they drift down to some ghost of a wetland past. Their mental impressions might be so deeply rooted that they don’t seem like memories any longer but instead are expressed as a gravitational constant that the ducks can’t ignore: Here. Come here. Home.

If that’s the case, I know the feeling.