Arts & Culture

The Lunch Counter

Fifty years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, a look at the past and promise of the most democratic restaurant space of all

Photo: Rush Jagoe

Lunch counters, with starburst stainless backslashes, vinyl spinner stools, and long tables of elbow-polished linoleum, are architectural and cultural icons. Everyman spaces, where lawyers and laborers sit side by side to savor burgers and fries and sweaty tumblers of tea, they were conceived as sites of workaday communion.

At their best, lunch counters reflect our egalitarian ideals. The problem is, for much of the South’s history, they were not at their best. Until the Civil Rights Act of 1964, many restaurants were reserved for whites, while black citizens ate their burgers and fries standing up, or at a cordoned section of the counter, or after walking around to the back door.

I spent grammar school mornings in the post-segregation 1970s on a Waffle House spinner stool, eating breakfasts of over-easy eggs and butter-troweled toast as blacks and whites alike slurped coffee from stoneware mugs, dropped quarters in the juke, and exchanged the affirming pleasantries that make restaurants incubators of community. Watching the grill cook at our local in Macon, Georgia, as he spatula-flipped patty sausages with his left hand and cracked eggs with his right, my father, who worked on federal civil rights cases in the sixties and seventies, would tell me stories of the struggle to desegregate the region and sketch the promise of gathering all at a common table.

I think of those morning discussions each time I take a seat at a restaurant with a counter. Even as I order a bowl of the cheddar-bound macaroni and cheese that Ashley Christensen serves at Poole’s Downtown Diner—a swish modern restaurant in Raleigh, North Carolina, that attracts an inclusive crowd—I can’t help but fix on that design form and on the role those counters played in our region’s tragic past. When I slide onto one of the stools at Poole’s serpentine counter and order an old-fashioned, I conjure how such places of pleasure were once sites of contention.

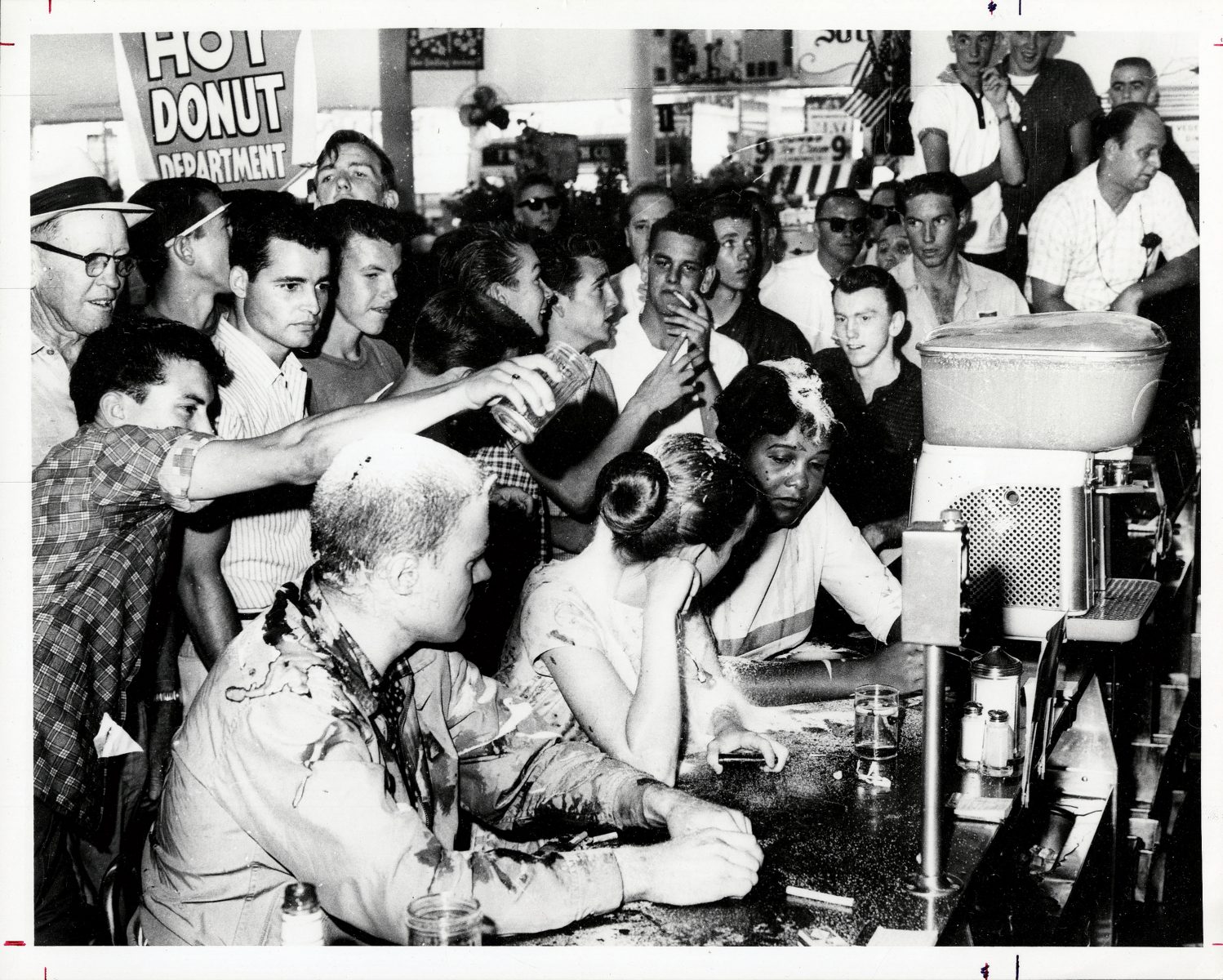

I’m not falling on my sword. I believe that an acknowledgement of our past better prepares me to enjoy the pleasures of this present. In that spirit, I recently took a stool at Brent’s Drugs, in Jackson, Mississippi, a model of the lunch counter form, with a boomerang-imprinted aquamarine counter and Tab placards mounted on the back bar. Two bites into a breakfast of fried eggs and stone-ground grits, I flashed to the ugly moment back in May 1963, when an integrated group, led by college students, attempted to gain service at a Woolworth’s lunch counter in downtown Jackson, while a mob of protesters threw salt in their eyes, dumped mustard on their heads, and stubbed lit cigarettes on their forearms.

Three miles and fifty-one years separate Woolworth’s then and Brent’s today. Neither distance seems great. Two generations after the Civil Rights Act legally desegregated America’s restaurants, hard appraisals are as necessary to our current understanding of good food as facing down the evils of factory-farmed pigs before ordering that next slaw-capped barbecue sandwich.

Photo: Fred Blackwell/McCain Library and Archives, The University of Southern Mississippi

Seed of Change

Angry protesters surround civil rights demonstrators during a sit-in at a Woolworth's lunch counter in Jackson, Mississippi, on May 28, 1963.

The role of lunch counters in the social life of our region began to change in February 1960, when four black freshmen at what is now North Carolina Agricultural and Technical University walked into an F. W. Woolworth Company store in Greensboro, North Carolina, and requested service. Protesters in Southern border cities like Baltimore and Oklahoma City had staged previous sit-ins, demanding equal treatment. But this one struck in the heart of the Deep South, where Jim Crow reigned. The students were quickly refused. A larger group of students returned the next day. All took their place at the counter and ordered food that never came.

Within two weeks, students in eleven cities had staged sit-ins, mostly at lunch counters in downtown department stores. They were organized and insistent. Students in Nashville, wary of violent reprisal, developed protocols: “Do show yourself friendly on the counter at all times. Do sit straight and always face the counter. Don’t strike back, or curse back if attacked. Don’t laugh out. Don’t hold conversations. Don’t block entrances.”

By the end of February, sit-ins spread to thirty cities in eight states. Some white merchants responded with harebrained strategies. Instead of serving an integrated crowd, department store and drugstore managers in Charlotte and Knoxville unscrewed the seats from their lunch counter stools. In the Carolina Israelite, North Carolina journalist Harry Golden unpacked the absurdity of the moment. “It is only when the Negro ‘sets’ that the fur begins to fly,” he wrote, proposing a tongue-in-cheek solution, the Golden Vertical Negro Plan, in which segregated sit-down lunch counters would be refashioned for integrated stand-up meals.

Photo: Bettmann/CORBIS

Moment of Promise

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act at the White House on July 2, 1964.

When President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, on July 2, 1964, he outlawed discrimination and segregation in places of public accommodation. Many restaurants integrated within the first week. On July 3, Cafe du Monde, the coffee and beignet stand in the French Quarter of New Orleans, served its first black customers without incident. On July 5, the Sun and Sand motel in Jackson, Mississippi, served its first black dining room client, but closed the swimming pool.

Others adopted the principles of massive resistance. The most well known included Maurice Bessinger of Maurice’s Piggie Park in Columbia, South Carolina, who integrated his barbecue restaurant after losing a Supreme Court battle but continued to fight through the 1970s, when he served as president of the National Association for the Preservation of White People and ran a losing campaign for governor while wearing a white suit and riding a white horse.

Some responses were more sophisticated.The owners of the Emporia Diner in Virginia developed a two-menu system. Blacks got menus with higher-priced fried chicken. Down in North Carolina, proprietors of Ayers Log Cabin Pit Cooked Bar-B-Que in the city of Washington took a cruder tack when they agreed to serve blacks but posted a sign by the register: ANY MONEY FROM NIGGERS GIVEN TO THE KKK.

When my friend Brownie Futrell was a boy, he asked his father, publisher of the local newspaper, what the sign meant. “It means we can’t eat here anymore,” came the answer. Futrell, a white son of the South, had to wait a long time before pondering a return. The sign remained in place until 1970, when the U.S. Attorney General filed suit to force its removal. True redemption came later, after Ayers closed, when the Solid Rock Holiness Church, a black congregation, began worshipping in that same space.

Old habits die hard. When I moved from Georgia to Mississippi in 1995, the Crystal Grill in Greenwood still displayed one sign that identified it as the Crystal Club, a name adopted in 1964 that defined the restaurant as a so-called key club, off-limits to blacks. As recently as 2001, I was turned away from a New Orleans restaurant when I arrived with a Korean American friend. “We can’t accommodate you,” the owner said as we peered past him into a half-empty dining room, draped in linen and set with gleaming flatware.

Today, the symbolism of the long unbroken table remains important, especially among Southerners schooled from infancy in Last Supper imagery. Sharing a meal signals social equality. Like sex, eating is a deeply intimate act. And no eating space is more intimate than the lunch counter, where diners stoop to sit and eat with people of other sexes and other races.

Many of us now live in gated communities and relax at private clubs. One of the drivers for that privatization was the struggle that began over lunch counters and escalated to include all restaurants. Remnants of the South’s post–Civil Rights Act flirt with key clubs can be glimpsed at schools like the University of Mississippi in Oxford, where I work.

Here, many of the white elite opt out of the university cafeteria system to eat at sorority and fraternity houses. Passage to those dining rooms is no longer determined by skin color, as it was in the 1960s. Today, class is as likely to drive campus segregation as race. And, yes, some black students now eat in fraternity and sorority dining rooms. But each time I watch a lunchtime stream of white students file into the sorority houses that line the street alongside my office, I can’t help but think that a new generation is losing out on the same opportunity I squandered back in the 1980s when I took my lunches of country-fried steak and green beans at the all-white Sigma Nu house at the University of Georgia.

All that said, there are frequent and sustaining flashes of contemporary hope. After a long absence, Southerners are returning to communal dining. Large unbroken tables, considered class equalizers during the French Revolution, copied by American hotels in the nineteenth century, and interpreted as lunch counters in the twentieth century, are regaining popularity. At restaurants like Snackbar here in Oxford, the communal tables are where the real gossiping and elbow rubbing and oyster slurping and community building go on.

On that recent trip to Jackson, I noted the same thing at the Beatty Street Grocery, a backstreet café that abuts a scrap metal yard. All of the action was at the counters, where white construction workers in dusty brogans and black government bureaucrats in gleaming cap-toes gathered at the same high-tops to eat three-buck fried bologna sandwiches on toasted white bread. Fifty years after the South fitfully desegregated its restaurants, the welcome table ideal has yet to be realized here. But that ideal may finally be in reach.

John T. Edge, writer and host of the television show TrueSouth, began contributing to Garden & Gun in its first year of publication. He is the author of The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South and House of Smoke.