Sporting

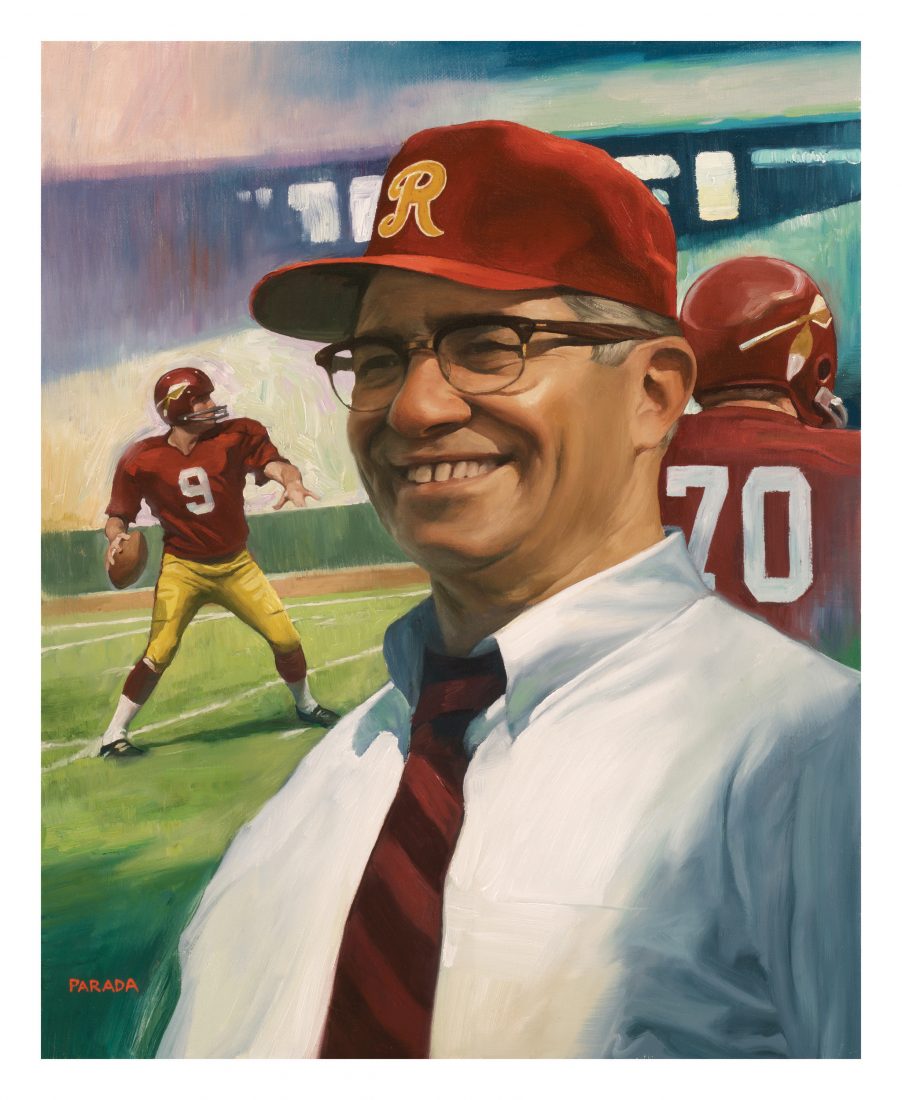

Vince Lombardi’s Southern Season

The Super Bowl trophy’s namesake spent his largely forgotten last season trying to turn a scruffy team of Southerners into NFL champions

Illustration: Illustration by Roberto Parada

He looked tragic, just tragic. It’s an image that’s never been associated with Vince Lombardi in the public imagination. But that’s how Green Bay Packers fullback Chuck Mercein remembers Lombardi when he retired as Packers head coach in 1968.

After almost a decade as the greatest head coach in the National Football League—five national championships and the first two Super Bowl victories—Lombardi decided he wanted to go out on top. He remained the team’s general manager, but when he wasn’t on the sidelines, it was as if the fifty-five-year-old was fumbling in the dark. The man animated by what he called “contest living” spent his days answering mail, attending meetings on Packer tax problems, and puttering around the stadium. “I miss the fire on Sundays,” he told the sportswriter W. C. Heinz that fall in Life.

Before the next season, though, Lombardi would find his way back to the light. He would leave Wisconsin for good to take a job as head coach of a ragtag club in Washington, D.C. There he would bring his fabled skills to a town, as President John F. Kennedy once unflatteringly described it, of “Southern efficiency and Northern charm” and be tested in unprecedented ways. “I’m going to lead this team to a Super Bowl,” Lombardi would declare to his men there.

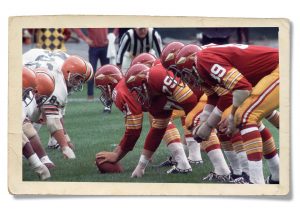

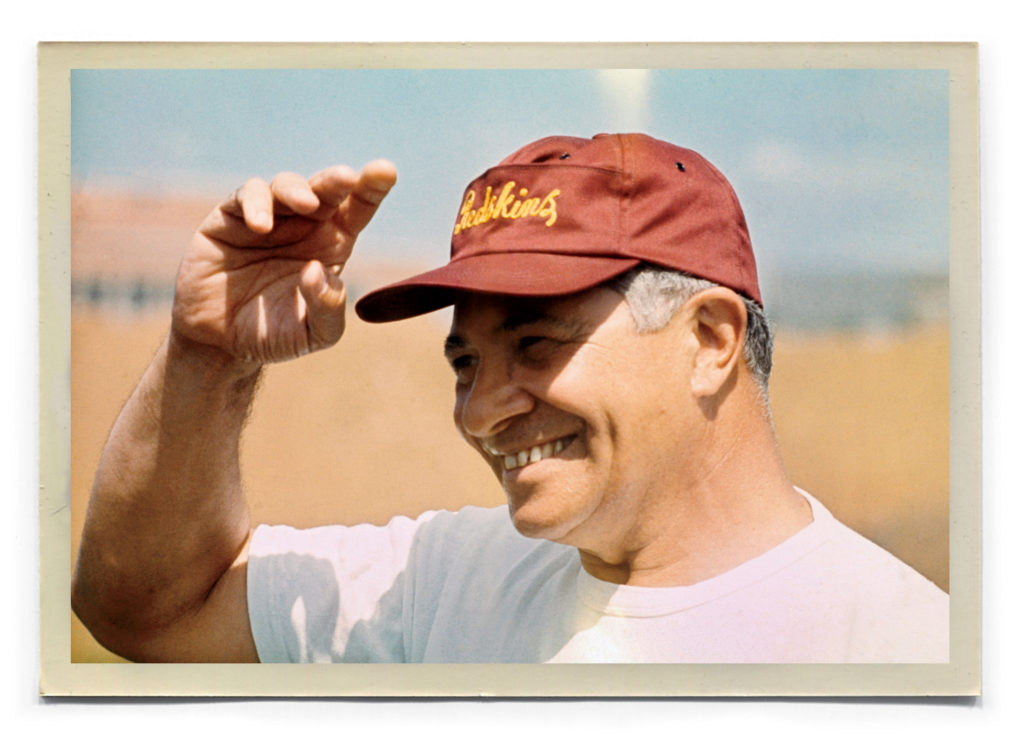

Photo: AP Photo/NFL Photos/Vernon Biever

The Redskins line up against the Browns.

When the country turns its attention to Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California, for the fiftieth Super Bowl this February, viewers will watch as the winning team is presented with an award that stands almost two feet tall, made of sterling silver by Tiffany & Co.—the Vince Lombardi Trophy. It evokes his epic time coaching the Packers, but for a select group of men who knew and played for Lombardi in 1969, the award also captures what they experienced in a tumultuous, all-but-forgotten run with the Redskins, when the man who famously declared “winning isn’t everything; it’s the only thing” traveled south to coach a team that hadn’t had a winning season in thirteen years.

Decades before the founding of the Atlanta Falcons, New Orleans Saints, Carolina Panthers, and Jacksonville Jaguars, the Redskins were the pro football team of the South.

George Preston Marshall of Grafton, West Virginia, founded the Boston Braves in 1932. Seeking more publicity, he renamed his team the Redskins in 1933 and moved it to Washington in 1937, where it became the first team south of the Mason-Dixon Line. A showman who wore a raccoon coat on the sidelines, Marshall made deals with radio stations throughout the South to carry Redskins games, and in the fifties did the same with television. An avowed segregationist who had long refused to sign black players, Marshall, in reaction to the burgeoning civil rights movement, in 1959 changed the lyrics in his team’s fight song from “Fight for old D.C.” to “Fight for old Dixie.”

Southern they were, but victors they weren’t. And that was the state of the team in the fall of 1968, while Lombardi languished in the second deck of the press box at Green Bay’s Lambeau Field. Desperate to spend Sundays back on the sidelines, he entertained generous offers for head coaching positions from the Philadelphia Eagles and a couple of budding Southern teams, the Atlanta Falcons and the New Orleans Saints.

It so happened that his deliberations coincided with those of a man in Washington—one of the greatest trial lawyers in U.S. history, Edward Bennett Williams. A minority shareholder of the Redskins, he had become the team’s president in 1965. A swashbuckler who could bring a jury to tears, Williams defended clients such as Jimmy Hoffa and Frank Sinatra. He ran with fellow big shots columnist Art Buchwald and Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee, and at games they would sit in the owner’s box at Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium in Southeast D.C.

But the Redskins were still a losing team and Williams wasn’t accustomed to losing. He wanted winners, and in 1968 there was no better symbol of victory than Vince Lombardi. That November, when the Packers traveled to Washington to play the Redskins, Williams visited with the coach. Even though the Packers stomped the Redskins, 27–7, the two men hit it off. “Washington is really a great place, isn’t it?” Lombardi said to Williams, in an exchange reported in Williams’s biography. “This is where it all happens.”

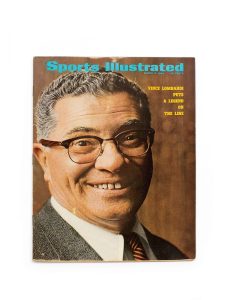

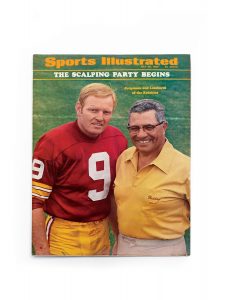

Photo: Margaret Houston

Sports Illustrated‘s March 3, 1969, cover.

In Williams’s mind, a vision started to come into focus: The town hadn’t had a winning football season since 1955. Lombardi was no longer coaching the Packers. He recognized that Lombardi’s great skill was his ability to take a team and make it national, and he went after him hard.

You can live in the White House, Williams offered. Appealing to Lombardi’s faith, Williams promised, You won’t even have to go to church. I’ll get Billy Graham to come to your house. Even if apocryphal, the lines pretty much capture Ed Williams’s real message: I’ll do whatever it takes to get you here. He even offered something Lombardi could never get in Green Bay: a financial stake in the team. “Lombardi was not well, and he wanted to provide for his family,” recalls John Kent Cooke, whose father then owned the largest percentage of the Redskins. It was enough to convince the coach to cut ties with the Packers, buy a house amid the rolling green lawns of Potomac, Maryland, and, as the cover of Sports Illustrated phrased it in March 1969, put “a legend on the line.”

It is not true that I can walk across the Potomac, even when it is frozen.” That’s what Lombardi said at a press conference when Williams introduced him as the new head coach of the Redskins on February 6, 1969. Washington “is the capital of the world,” Lombardi announced. “And I have some plans to make it the football capital.”

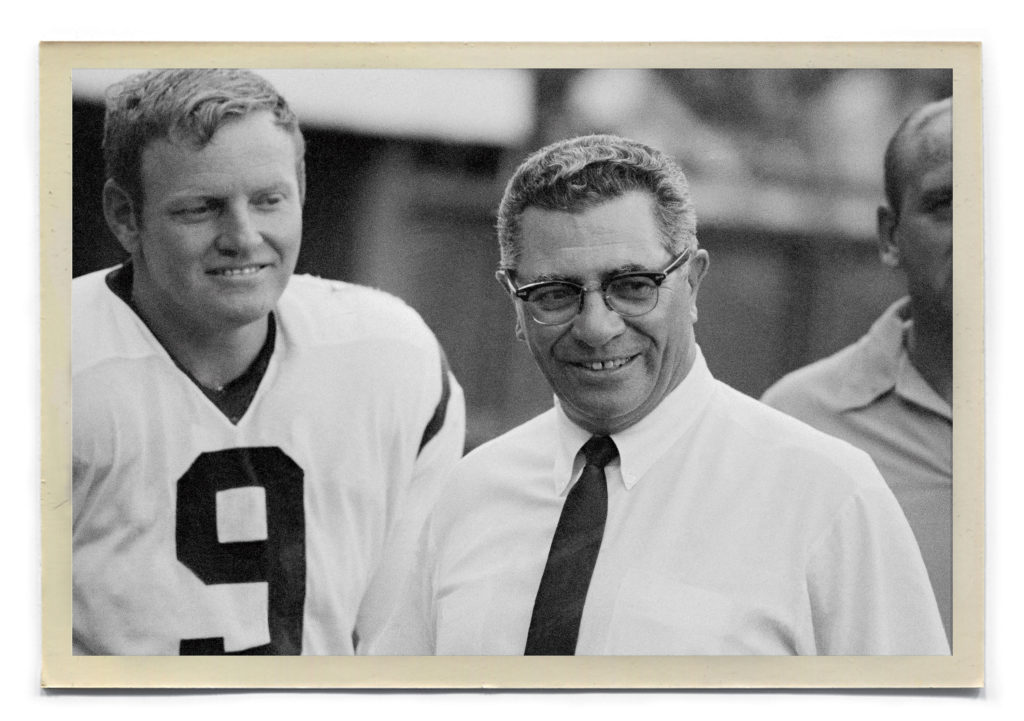

Photo: Bettmann/CORBIS

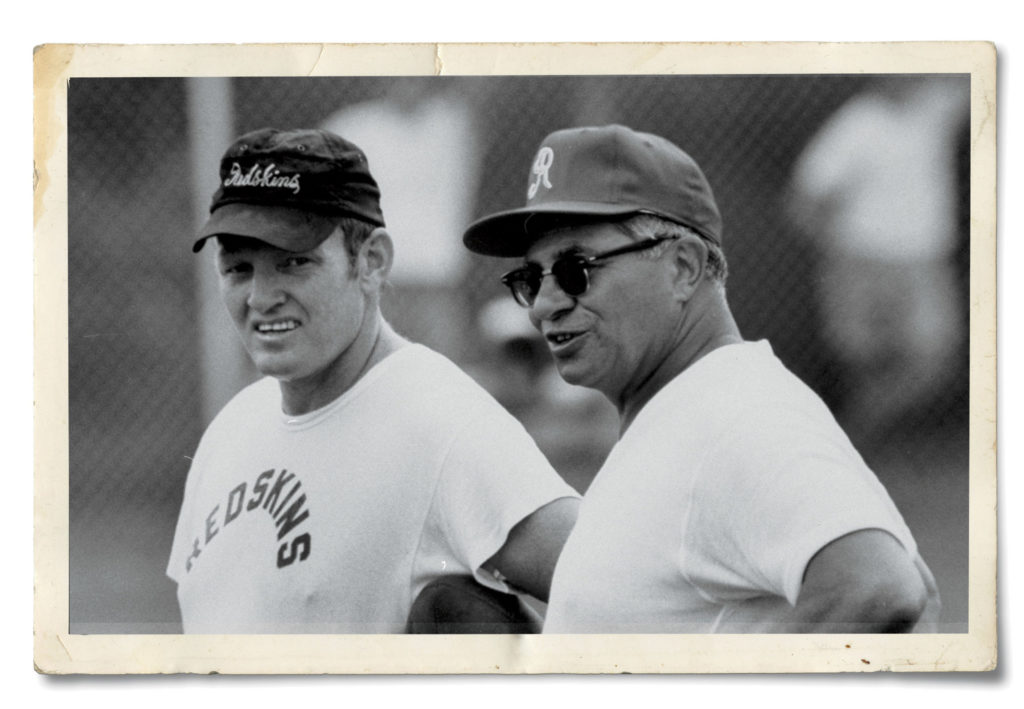

Field Generals

Quarterback Sonny Jurgensen with Lombardi on the sidelines in 1969.

The news even seemed to eclipse the buzz surrounding the just-inaugurated president, Richard M. Nixon. The city was trying to heal from the riots sparked by the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.—violence so intense that President Lyndon B. Johnson had dispatched thousands of federal troops to restore order. Now Vietnam seemed just as divisive. Suddenly, Lombardi was the hero the capital needed.

He might have wanted to find one himself once he met the Redskins—low draft choices, free agents, aging players. Even Williams admitted that his guys were “total rinkydinks,” according to his biographer, Evan Thomas. Still, the city remained loyal.

“I came to the Redskins in 1966 when Washington was going through its integration phase,” recalls the safety Brig Owens, who is black. “If people knew you were a Redskin, that was it—you were one of the guys. It changed things in terms of places you could go and where you lived. We moved into a predominantly white area and were welcomed with open arms.”

Those benefits also inured in the opposite direction. “My wife picked me up at the airport, and to get to our place where we lived in Maryland, it was a lot quicker to go through town,” recalls the white linebacker Chris Hanburger. “All of a sudden we’re in the middle of the riots. There were people all over the streets and everything. I was seeing them rock cars, and I’ve got my wife and kids in the car. It just so happened that some of these people recognized me [as a Redskin] and they escorted me. They got me up on some sidewalks to get around stuff and got us through.”

Despite the riots and political turmoil, D.C. “was a little more charming than what Kennedy said,” recalls the longtime Washington journalist Cokie Roberts, a native Louisianan. “It was a much smaller city, much less sophisticated, and much friendlier than it is now.”

For many Southerners in D.C., those were halcyon days. Sam Ervin of North Carolina, John Stennis and James Eastland of Mississippi, George Smathers of Florida, Richard Russell of Georgia, and Strom Thurmond of South Carolina were the titans of the Senate. “When I went up there with Ervin in 1964, fresh out of Carolina, you’d walk around Washington and everywhere you looked were people from the South,” recalls Rufus Edmisten, who worked as a Senate counsel. “The difference between now and then was that everybody didn’t rush home on Thursday to do fund-raising. We had massive parties back then.” And Sundays meant Redskins games.

“Back then you didn’t have all these so-called ethics rules,” says Edmisten, who later became deputy chief counsel of the Senate Committee on Watergate. “Somebody would drop off a batch of Washington Redskins tickets and we’d divvy ’em up. Nobody was being bribed, and nobody came in and tried to make you vote for something—you just went to the games.”

Lombardi’s team also included a core group of Southerners. Sam Huff, the pride of Edna Gas, West Virginia, had been a star linebacker for the New York Giants, for whom he started in the Greatest Game Ever Played—the 1958 championship against the Baltimore Colts. “I was good at kicking ass,” Huff tells me over lunch at the Red Fox Inn and Tavern in Middleburg, Virginia, where he now lives. Huff joined the Redskins in 1964 and retired in 1968, but when Lombardi arrived he brought Huff back as a player and assistant coach. Chris Hanburger was from the University of North Carolina. Offensive lineman Len Hauss had played at Georgia. Linebacker Tom Roussel was from the University of Southern Mississippi. And then there was number 9, quarterback Christian Adolph Jurgensen III, a.k.a. “Sonny,” a thirty-five-year-old redhead from Wilmington, North Carolina, who had played Duke football. He was known for a potbelly that people said jiggled like Jell-O when he threw. “You pass with your arm, not your stomach,” he’d tell critics.

Photo: Wally McNamee/CORBIS

The coach and his quarterback talk during practice.

Jurgensen had muttonchops and hosted The Sonny Jurgensen Show, on channel 9. He drove around town in a Mercedes with the license plate SJ-9, a flashy statement in the late sixties. The year before Lombardi arrived, the NFL fined him five hundred dollars for saying, “The only difference between [coach Otto Graham] and me is he likes candy bars and milk shakes and I like women and Scotch.”

Jurgensen says his reputation was exaggerated. “Media hype,” he recalls, remembering in particular a 1968 Saturday Evening Post feature that showcased his taste for the hard stuff. At the time, though, he embraced the persona. One story reported in the magazine: Following an away game, a friend asked Jurgensen about his passing arm.

“How’s the arm feel?” he asked.

“Terrible,” Jurgensen replied. “Hurts so much I’m even drinking left-handed.”

Still, he’d won the NFL passing title in 1967, thrown for 32 touchdowns in one season, and completed 508 passes in another. The Eagles had drafted him in 1957 and traded him to the Redskins in 1964. He was happy about the trade, he says, because playing in Washington enabled his family in Wilmington to watch him on television.

Lombardi recognized Jurgensen’s talent, telling him at the beginning of the 1969 season, the quarterback recalls, “We wouldn’t have lost a game if you’d been at Green Bay.” But despite Jurgensen’s exceptional passing skills, the Redskins still hadn’t been able to eke out victories, finishing the previous year with a 5-9 record.

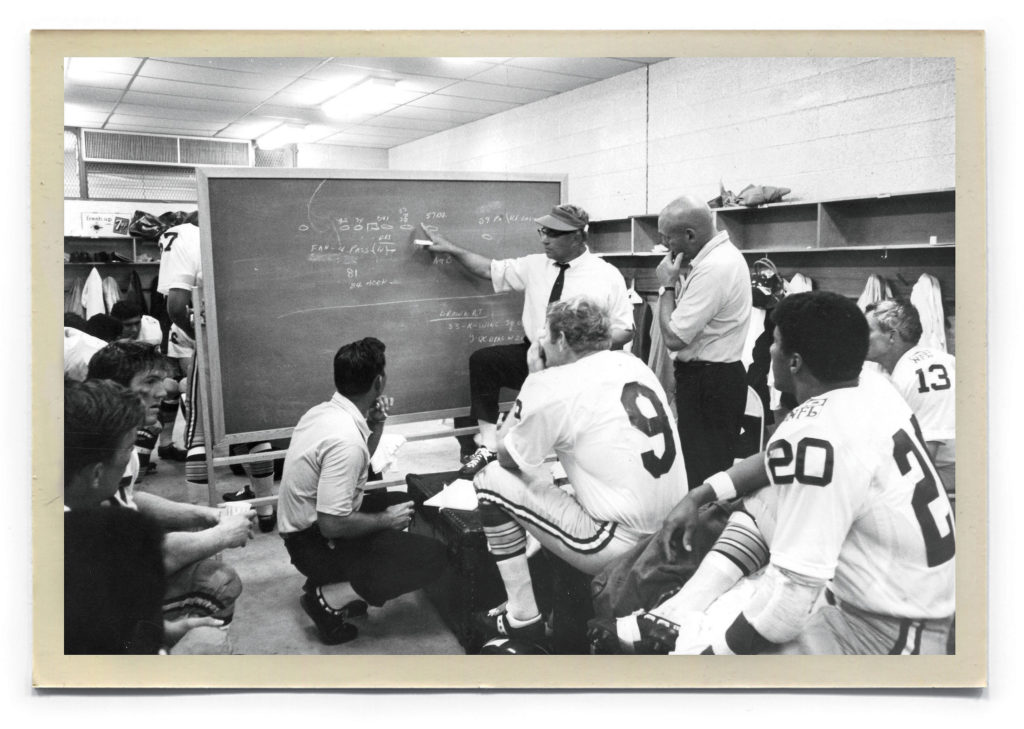

Photo: AP Photo/NFL Photos/Vernon Biever

Players listen to Lombardi at halftime during the first game of the season, in New Orleans.

Recognizing that with Lombardi now running the team, the Redskins would mean more to the city than ever, a writer at Washingtonian magazine, Tom Dowling, traveled to Green Bay to report on the history of Washington’s new coach. Having liked Dowling’s cover story, Lombardi invited him to shadow the team for the entire season, giving him one-of-a-kind access. Dowling watched training camp, observed practices, listened to Lombardi’s locker-room speeches, and tape-recorded interviews with the coach and players that became the basis for a 1970 book on Lombardi, Coach.

As we sit in Nanny O’Briens pub in Washington’s Cleveland Park, Dowling says he was struck whenever he saw Lombardi. “I’ve met a fair number of so-called great men in my days as a journalist, and I can say that he was the only one who radiated an instantaneous sense of command. You were stirred. Lombardi just had it.”

Once in Washington, Lombardi, who had never had a losing season as a head coach in the NFL, wasted no time making known his intentions. “I’ve never been with a loser, gentlemen, and I don’t intend to start at this late date,” he announced to the team on July 10, 1969, in a speech at training camp. “Winning is a habit, gentlemen. Winning isn’t everything; it’s the only thing. If you can shrug off a loss, you can’t be a winner.…Gentlemen, let’s be winners! There’s nothing like it.” Perhaps his confidence was bolstered by the fact that when he started at Green Bay in 1959, the Packers hadn’t had a winning season in twelve years. But Lombardi knew he had to prove himself in this new environment, where some people like the Birmingham News columnist Benny Marshall regarded him as “a poor man’s Bear Bryant.”

That day, though, the Redskins knew they were listening to a champion, and at the end of his talk, Lombardi raised his hands to show the men his sparkling championship rings.

While most of Washington regarded landing Lombardi as a miraculous turn of events, fear was coursing through the Redskins. Players had heard the tales from Green Bay and agonized over whether they’d be up to Lombardi’s standards. “I had played seven or eight years and not for any coaches who punished me for the guard making a mistake, or the end forgetting the count, or for the back fumbling,” Len Hauss says. “And knowing that was his method shook some of us and made us concerned about how we were gonna do this.”

The fear of getting traded or cut by Lombardi permeated the season. Players took measures to get in top physical shape. “Sonny came into training camp at about a hundred and ninety pounds—he didn’t have a gut on him,” Brig Owens says.

“Weights and running?” someone asked him.

“Naw, Cutty and water,” he joked, in an exchange printed in Life.

The coach operated on what the guys called Lombardi Time. During training camp, evening meetings began at eight o’clock. If Lombardi arrived at ten minutes to eight, and a player came in after that, he was considered late and fined. “So you showed up twenty, even thirty minutes early,” Hanburger says.

Lombardi believed in “red meat” football—blocking and tackling. But he dissected everything to a fare-thee-well. How you determined whether you went right or left. How you learned where the other guy was going. “It was a huge endeavor to learn Vince Lombardi football,” says Dowling, who sat in on these detailed sessions.

On the practice field near the Anacostia River (players dressed in RFK Stadium, and then walked through a tunnel and a parking lot to get to it), Lombardi drills felt like getting hit in the head with a two-by-four, f-bombs dropping on all sides. “What the hell kind of play was that?” he roared. “What the hell is going on here, anyway? You’re trying to catch the ball with your wrists. In case you haven’t heard, the idea is to keep your eye on the ball. You could not hit a bull in the ass with a handful of peas.” And his all-time favorite, reserved for the most egregious errors: “You are really something, you are, Mister.” Hanburger recalls that Lombardi always had a priest on-site. “After being with him for a couple of weeks, I said to myself, ‘With his language, it’s no wonder he’s got a priest here.’”

Hauss remembers a line by Packers defensive tackle Henry Jordan: “He treats us all the same—like dogs!” “That’s kind of the way it was at the Redskins, too,” Hauss says. “But it wasn’t funny when you were one of the dogs.”

As Lombardi and the team readied for their debut against the Saints, other coaches in the league had grown weary of the legend. “I’m tired of all this Lombardi business,” Miami Dolphins coach George Wilson told the Associated Press. “Everyone makes him out to be such a great coach. Given the same material, I’ll beat him every time….I don’t holler at a fellow in front of his teammates.…That’s just a big show and I’m not going to do it.” It was as if they couldn’t wait to see him fail. Tom Landry had served as a fellow assistant coach with Lombardi for the Giants in the fifties, and as head coach of the Dallas Cowboys, he had coached twelve games against Lombardi’s Packers, losing ten of them. Now Landry would have to face Lombardi yet again. “I always look forward to competing against him,” he told the AP. But players had heard that he’d said he was “tired of sucking hind teat to Vince Lombardi.”

Even before the Redskins boarded the plane to New Orleans, Lombardi was rattled. He would sit in his office facing the White House and worry. He had to win. Saints head coach Tom Fears had been a Lombardi protégé in Green Bay, and losing to him would be humiliating.

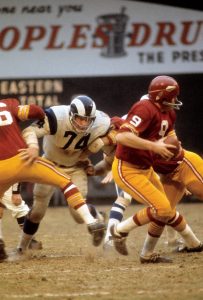

Photo: Art Shay/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

Jurgensen in action.

“That New Orleans, they’re something else,” Lombardi confided to Dowling. “Al Hirt blowing that damn trumpet on the sidelines, and they put up two big speakers on either end of the visiting bench, blaring right into your ears. Eighty thousand people screaming every time you’ve got the ball so you can’t even hear your own signals, and when they’ve got the ball you can hear a pin drop. You know what I’m going to do? I’m going to take a pair of wire-clippers down on the sidelines, and the first time I hear Al Hirt blowing that damn trumpet in my ear, I’m going to cut the speaker cords. No, on second thought, maybe I’ll have someone from the cab squad cut them.”

Lombardi opted not to resort to those measures and instead tried to focus on the game itself. But after the intensity of a week’s practice, by kickoff he arrived almost useless. He’d been like that at Green Bay, so emotional during games that he would explode in anger or elation, incapable of calling plays. TV producers loved it. Lombardi electrified their broadcasts. While he stalked up and down, yelling, his assistants and players had to rely on what they’d learned from him during the week.

“This was no Dick Vermeil, combing his hair on the sidelines in case the TV cameras came up for a close shot,” recalls Dowling.

In New Orleans, as more than seventy thousand spectators looked on, Jurgensen threw for three touchdowns, and when the game ended, the Redskins had defeated the Saints, 26–20. They came back to Washington heroes (Lombardi even allowed the players to have beer on the return flight). But their first home game was still three weeks away. In the meantime, the Redskins lost to the Cleveland Browns, 27–23, and tied the San Francisco 49ers, 17–17. After that, Lombardi told reporters in California, “I’m happy to come away with my life.”

Photo: AP Photo/NFL Photos/Vernon Biever

A sign at RFK Stadium during a game against the Packers in 1968.

On October 12, the Redskins played the St. Louis Cardinals before a roaring crowd of fifty thousand in RFK. In the first quarter, Redskins running back Larry Brown ran twelve yards for a touchdown. Jurgensen passed to Jerry Smith for another. And on they marched. The Redskins won, 33–17. Headlines in the Washington Evening Star told the tale: VINCE ALTERS EVERYTHING and REDSKINS’ SHARP SHOWING STIRS UP TALK OF MIRACLE.

The team was the talk of Washington. If you weren’t in the stands at RFK, you watched on channel 9 or listened on WMAL 630 AM. During games, it was said, D.C.’s crime rate dropped. Dowling remembers attending a cocktail party held at the poet Carolyn Kizer’s house that included Jurgensen and some fellow Southerners: the journalist and author Barbara Howar, Arkansas senator J. William Fulbright, and the author James Dickey. “The only person anybody was interested in was Sonny,” he says.

The Redskins next defeated the New York Giants and the Pittsburgh Steelers, but Lombardi thought the victories were wobbly. In a press conference, a reporter asked whether the team could keep bumbling and winning. “They’re playing with everything they’ve got and once in a while they put it all together for a long drive,” he answered. “You can’t give more than the best you got. But obviously we can be outclassed. We can be overpowered.”

Back in Washington, Lombardi readied the team for the Baltimore Colts. He went through his usual training exercises and made players study film of the opponents with religious zeal. Then he brought everyone together and said he wanted to lead the Redskins to a Super Bowl. “Maybe not this year, maybe not next year,” he said. “It might have to be the year after. Some of you won’t be on the team then.”

He picked the wrong time to talk about Super Bowls. The Redskins were just trying to get through the week and last until Sunday, coping with injuries and the realization that they weren’t the Packers superstars Paul Hornung and Bart Starr. It was still October, and to visualize a future that far ahead threw the team off balance. The Colts devastated them, 41–17.

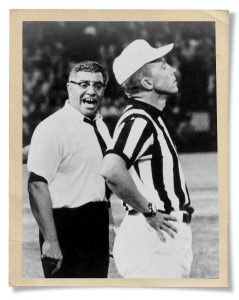

Photo: AP Photo/NFL Photos/Vernon Biever

A Legend on the Line

Lombardi gives an official an earful.

The next Sunday, in a game against Philadelphia at RFK, the wheels came off the bus. A controversial pass interference call led to an Eagles touchdown in the fourth quarter and a tie game, 28–28. Lombardi went ballistic, hurling one profanity after another at the officials. The players couldn’t believe what they were seeing. The coach’s veins popped and he was angrier than he’d ever been on the sidelines. Then he turned his fury on the guys. He said that it was the worst-played football game he’d ever seen. “Some of you,” he said, “won’t be here on Tuesday.”

“He’s just a poor loser,” one player told Dowling. “I hate to say that about him, but…it’s as simple as that.”

The team was in turmoil. Between Lombardi’s meltdown and his continued tinkering with the roster—making cuts and even signing some former Packers who were free agents (Mercein, guard Dan Grimm, receiver Bob Long)—things were looking bleak. Going into the game with the Cowboys, Dowling recalls, running back Charley Harraway told him he believed an “alien force” had seized hold of Lombardi and the team. The man who had coached with such a clear vision at Green Bay—“He told us his goal, we all knew it, that’s where we were headed, and you didn’t want to get in the way,” as Mercein recalls—seemed lost. On November 16 at RFK, with President Nixon in attendance, the Cowboys brutalized the Redskins, 41–28.

Maybe the prospect of facing the great Vince Lombardi threw the Atlanta Falcons off their game. Maybe it was an injury to their linebacker Tommy Nobis. Or just maybe that alien force had set its sights on Richard Nixon and decided to release its grip on the Redskins. Whatever the reason, the sun came out again the next week at RFK. In one play, after a lob from Jurgensen, Harraway ran sixty-eight yards for a touchdown. The Redskins drove and drove, and won, 27–20.

Toward the end of most seasons, when players are exhausted, it’s almost impossible to get a fresh perspective. But somehow late that fall, a winning season was within reach. Despite a loss to the Los Angeles Rams on November 30, Lombardi seemed renewed. Something mystical was breaking the Redskins’ way. Even the referee who’d made the disputed call in the Eagles game admitted he might have erred.

On December 7 in Philadelphia, the Redskins avenged themselves against the Eagles, defeating them 34–29. A week later, back at RFK for their final home game, they beat the Saints, 17–14. With one game left, it put their record at 7-4-2, ensuring a winning season. Afterward, Lombardi proudly told the press that Jurgensen was the greatest quarterback he’d ever coached, perhaps the best the game had seen.

Just before Christmas, the team flew to Dallas for their final game. They lost, 20–10. Tom Landry could afford to gloat a little, but it didn’t seem to matter. The Redskins had a future. Maybe a Super Bowl was possible. On the flight back to Washington, Lombardi said, “The Packers were young and they were deep in talent. It was all there. You could see it, you could feel it. The Redskins? They’re not that young, not that talented. But we’ll be there, we’ll be giving it what we’ve got. Hell, there’s no other way.”

Photo: Bettmann/CORBIS

Lombardi cracks a smile on the first day of Redskins training camp.

I’m telling you, every time I sit down I get pains.” Lombardi was talking with Dowling, just before the Dallas game. “Football kills you emotionally,” he confided. “The tension’ll tire you out more than the physical exhaustion will.…The game wasn’t as complex ten years ago as it is today.…You were able to innovate more than you can now.…In the old days, it was a part-time job for people who wanted to work outside.”

By June 1970, the pain had become so unbearable that Lombardi checked into Georgetown University Hospital. The diagnosis came back as colon cancer. During his treatments, the players who lived in Washington year-round used the campus athletic field to run their own practices. One day, Lombardi had Ed Williams’s chauffeur bring him by.

“We were doing his notorious up-and-downs that he had us do all the time,” Hanburger recalls. “He got out of the car and talked to us for a few minutes. But he didn’t say much, and turned and got back in and left.”

It’s a temporary setback; he has every chance of recovering—that’s what Williams and the Redskins were saying. But they must have known. Lombardi tried to coach a scrimmage and address the team in the locker room. Frail and exhausted, he couldn’t make it through.

Photo: Margaret Houston

Season of Promise

SEASON OF PROMISE

Sports Illustrated‘s cover from July 28, 1969.

In late July, Lombardi was readmitted to Georgetown. The men who had played for him in Green Bay and Washington poured in to pay their respects. Lombardi explained to them that a team is like the spokes of a wheel—they come into one place and then go out, but together form a core that makes the wheel steady. “He told us that we had to stick together like those spokes,” Owens recalls. Jurgensen remembers that when he went to see Lombardi, the coach reviewed the upcoming teams and their defenses—Now you know the system, Sonny, he said. “He was thinking of that stuff up until he died,” Jurgensen says.

Time runs out for Vince Lombardi. The headline appeared on the morning of September 4, 1970. Lombardi was dead at the age of fifty-seven. A few days later, NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle announced that the league would rename the Super Bowl trophy in the coach’s honor.

That final season of 1969, Lombardi had transformed the Redskins into a national team, and they would go on to become a powerhouse in the eighties and early nineties. But for the men who played for Lombardi that year, the memories remain bittersweet. “I often go to bed at night thinking what would have happened if,” Mercein says. “If he had lived. He had this great quarterback in Sonny, and to see Coach take the Washington Redskins right where he took the Green Bay Packers…” Mercein trails off, imagining what might have been.

In January 1973, some of the Redskins from that season flew to Los Angeles to play the Miami Dolphins. They’d made the cover of Sports Illustrated with the headline WASHINGTON IS A NO. 1 POWER. They lost to the Dolphins that day, 14–7. But the game was the Super Bowl.