Sporting Life

The Wild Zen of Flip Pallot

The world-famous angler, archer, TV personality, woodsman, and sage has always lived life by one rule—follow your heart

Photo: William Hereford

There is a certain manner of listening to a wild turkey at dawn, a conscious and intentional listening that involves not just the ears but the body, soul, and mind. You sit quietly in the early light, leaning into the woods, head cocked, perfectly still. You monitor each breath and heartbeat, aware that the rustle of your shirt as your chest rises and falls, or the rush of blood in your ears, might muffle the faintest gobble. At times you very nearly believe you can prompt a tom to gobble through the sheer force of your will—that if you listen so fixedly and wish it so deeply, your desire might work through the woods like a faint breeze, just enough to provoke a bird to sound off.

Which is how we are trying to listen, but it’s not working this morning.

“Too many crows,” Flip Pallot mutters. He sits beside me, our backs to a live oak, a Central Florida pasture strung with dewy spiderwebs unfurled at our feet. We’d walked into the woods in the light of a half moon, with fireflies in the wet grass and barred owls countercalling from cabbage palms silhouetted against the dark sky. Now a half dozen crows caw back and forth, raucous and unending. On still, quiet spring mornings, a tom will typically answer a crow’s caw with a resounding gobble, giving up its position to those who lean into the woods. Now Pallot shifts a tall leather snake boot and shrugs. He pulls a plastic bag of leftovers from last night’s dinner from a small pack. “So many crows,” says one of the world’s most famous saltwater anglers, voice muffled with flank steak, “that the turkeys are ignoring them.”

Pallot shrugs. Too many crows. Not much to do about that. You want a carrot?

What is striking about this moment is that the man sprawled beside me, in blue jeans and a straw hat spray-painted green (he does not believe in traditional camouflage), could be anywhere else in the world. In the Bahamas chasing bonefish, in New Zealand chasing trout, in Costa Rica sticking sailfish with flies the size of cigars. Pallot is arguably the most famous angler in the history of saltwater fly fishing. His ESPN television show, The Walker’s Cay Chronicles, debuted in 1992 and was at times during its fifteen-year run the highest-rated outdoor show on television. Pallot helped design the world’s best-known flats skiff and cofounded the company that makes them: Hell’s Bay Boatworks. He’s been a technical consultant for many of the leading brands in the industry. Along the way, Pallot gained a reputation as a sage and a sort of grizzly-bearded wisdom keeper for the increasingly technological pursuit of fly fishing, creating an ethic and an aesthetic of the saltwater lifestyle that inform the sport deeply even today. And he still fishes and leads trips around the world, to places he has fished many times.

Photo: William Hereford

Pallot, who prefers hunting with a longbow, takes at least one practice shot every morning.

Places he could be today, except for this: Flip Pallot loves to hunt turkeys even more than he loves to fish. In fact, one of the world’s most recognizable anglers is, at heart, a hunter. He hunts deer, hogs, and turkeys nearly year-round, and rarely buys meat from the grocer. He grew up hunting, and for years before his television career, he guided hunters for game as varied as hogs and gators. A passionate traditional archer, he got his first longbow when he was a junior in high school. He still sends out turkey feathers from his kills to arrowsmiths who fletch his custom arrows with

the vanes.

We stick it out for another few hours, but we have three more days to chase birds through the Florida flatwoods, so there’s no reason to wear out our spines quite yet. Pallot unfolds his six-foot-one-inch frame and steps out to pull the turkey decoy as I gather our packs and water bottles for the hike out. When I look up, I see something not many of Pallot’s fans have seen: the man walking on dry ground. They’ve seen him countless times standing on the deck of a boat fighting a tarpon or a permit, or on the poling platform of a skiff, or prowling flats for bonefish. But they’ve not seen this loose-limbed, unencumbered gait. He strides through the dappled sunlight with each hand slightly cupped, his torso bent slightly forward, unrushed but purposeful. At the age of seventy-five, he walks like a man who still has places to go.

My-am-ah. Pallot pronounces the word as he heard it as a child. It’s a place, frankly, that no longer exists. That’s where he grew up, not in the modern Miami, the megalopolis of six million souls, but in a relatively small town where a quarter of the residents spoke Spanish, many of them from the Cuban diaspora, the “Golden Exiles,” who fled the island after Castro’s rise to power. Pallot’s My-am-ah was this kind of place: As a kid, he had a buddy with a turkey-loving, short-legged beagle named Bullet, and the boys would let Bullet loose in Big Cypress Swamp west of Homestead. The dog would chase a turkey, and the boys would chase the dog until the turkey flew into a tree. They’d shoot the bird with a .22 rifle, cut the spurs off, and sell them to Miami Cubans who would glue the spurs to the legs of their fighting chickens.

“We could get thirty bucks for a pair of good spurs,” Pallot says. “That was my My-am-ah. I don’t know what that place is now.”

Dade County back then was a place small enough for incredible happenstance, and for united fates that would ultimately shape the burgeoning sport of saltwater fly fishing. In 1959, while hanging out at a local tackle shop’s shrimp tank, Pallot met a young Cuban who had just arrived stateside that day: Chico Fernandez, an angler destined for a limelight similar to Pallot’s. Norman Duncan was another boyhood pal. He would devise the Duncan Loop, more commonly known as the Uni Knot, one of saltwater fly fishing’s foundational knots. In the first grade, Pallot became friends with John Emery, who would become one of the Florida Keys’ most famous guides and highly sought custom reel makers. As kids, this foursome coursed along the Everglades and the Keys. They cruised the Tamiami Trail, a.k.a. U.S. 41, which cleaves the Everglades, watching for tailing snook in the roadside canals. They paddled air mattresses into Biscayne Bay to cast for tarpon and pompano. The childhood friends wound up at the University of Miami together, taking night classes after which they practiced casting in the college’s well-lit parking lot.

After graduating, the foursome split. Chico Fernandez went to work in accounting for an infant hamburger chain: Burger King. Pallot joined the U.S. Army, and spent the years from 1963 to 1967 as a linguist in the jungles of Panama. When he returned to civilian life, he landed a job as a banker, a stint he morosely describes as “spending my days helping other people achieve their dreams, while watching mine wither.” In the early 1980s he walked away from the nine-to-five for good. For a dozen years he guided hunters and anglers full-time, from Florida to Montana. As his guiding reputation grew, Pallot hosted his own local television show and made guest appearances on well-known series such as ABC’s American Sportsman. But celebrity-driven story lines were their standard fare, and Pallot wanted to plow fresh ground. “I’d been nursing an idea for a different kind of television show,” he recalls, “one with high production values but no movie actors and no opera singers. My thinking was, everybody has a fishing buddy, someone they love to spend time with and share adventures with. I wanted to highlight those relationships and feature real-deal people. That was very important to me.”

Photo: William Hereford

A rabbit strip streamer.

Pallot’s television aspirations took off thanks to a life-changing twist of fate. His wife, Diane, was an airline attendant and serious fly angler herself, and on one of her flights she met a wealthy businessman whose family owned a tiny cay in the northern Bahamas. It was a mecca for offshore fishermen, but the owner hoped to develop a world-class

fly-fishing lodge there. He hired Pallot to jump-start the flats fishing business, and Pallot soon realized he’d found the center of gravity for his new enterprise. Basing the show loosely at Walker’s Cay rooted each episode in a pleasing narrative arc: The fishing action might take place in Florida, Costa Rica, or China, but Pallot’s home base at the tiny, idyllic cay gave it a comforting homegrown appeal.

In 1992, the first episode of The Walker’s Cay Chronicles aired on ESPN, and Pallot’s avuncular approach—not to mention his rum-smooth voice-overs—struck a chord with the public. Pallot put the best fishermen in the world on his show, and was happy to be upstaged. Viewers actually learned how to fish by watching the show, but there was no infomercial content. “If you wanted to know what kind of reel was being used,” Pallot says proudly, “you had to stop the VCR and rewind the show. The whole thing was about telling a story, and people were hungry for that.” It was quickly the highest-rated series in outdoor television. “The show just blasted onto the scene,” he says. “New Guinea, Australia, Midway Atoll in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. This was early in the exotic fly-fishing era, so everything we did seemed very new and different.”

His growing fame was unfamiliar water, too. The rising tide of saltwater fly fishing was carrying a number of high-profile anglers to levels of stardom unknown in the business, among them Pallot’s longtime buddy Chico Fernandez—the two stay in close contact even today— the pioneering tarpon guide Stu Apte, and Jose Wejebe of the wildly popular show Spanish Fly. One of the most famous of them all, Lefty Kreh, had moved to Florida in the early 1960s, and he and Pallot became lifelong friends.

“Flip’s show was different because he was different,” Kreh says. “Here’s this big, bearded, soft-spoken thoughtful guy whose mission was more about storytelling than it was about fish catching. He used fishing to tell about the people who lived in these amazing places, and what the local culture was like, and how communities interacted with the environment. He didn’t sell tackle. He sold story, and there was nothing like it on television.”

Photo: William Hereford

A rod at the ready.

Pallot kept it in perspective. “I’m a fisherman, not a rock star,” he says, “but recognition can be intoxicating.” He remembers the first time he was faced with the reality that life had changed forever. Early on, he and Diane were in Wintergreen, Virginia, presenting a seminar, and he’d driven straight from Florida into a snowstorm with no socks. They dashed into a tiny country store and Pallot was working his way down an aisle when he noticed a young lady staring at him.

“She goes, ‘Holy shit, you’re Flip Pallot! My husband is going to shit over this!’ So I just replied, ‘Well, I hope everything turns out okay for him after that.’” And then she asked Pallot for his autograph, the first time anyone had ever done that. Pallot and the young fan frantically searched for a scrap of paper but couldn’t come up with anything. Desperate, the woman grabbed a box of Cocoa Puffs off the shelf and stuck a Sharpie in Pallot’s hand. “I didn’t know what to say,” he says, laughing. “I wrote something like, Dear Fred, have a nice life, and she was thrilled to death.”

The Walker’s Cay Chronicles had a larger cultural impact than Pallot’s being recognized in the cereal aisle. In many ways, he was on the leading edge—arguably he was the leading edge—of a new way of approaching and appreciating the outdoors.

“We’d watch the show in college, and then we couldn’t wait for spring break so we could go do this stuff we saw on television,” Ryan Seiders recalls. After college Seiders built fly rods full-time and met Pallot at trade shows across the South. When he and his brother, Roy, started Yeti coolers in 2006, Pallot was the brand’s first ambassador. “He had such a huge influence on introducing people to his style of fishing, poling boats in shallow water, but it went way beyond that. He helped bring about a new kind of lifestyle, an approach to fishing and travel and adventure that no one had seen before.”

Photo: William Hereford

Casting on Mosquito Lagoon.

Pallot laughs at the notion of his being a lifestyle pioneer. “We didn’t know what that word lifestyle even meant,” he says. “We were just doing our thing.” But as more fishing shows cropped up in the wake of The Walker’s Cay Chronicles’ success, he says, “the footprint became broad enough that it took on a momentum that we as a single show couldn’t fulfill. And it was amazing to watch this idea of fly fishing as a lifestyle, not just a passionate hobby, take root.” Pallot remembers when the brand Tarponwear burst onto the scene with eighty-five-dollar fishing shirts. Soon there were saltwater-lifestyle shoes, glasses, watches, belts. “All of a sudden there were bonefish lagers and dry-fly ales,” he says. “It just went nuts. People had never had the appetite before, then suddenly they had the steak and everybody stuck a fork in it.”

Fame, even the level afforded someone in such a relatively small niche, is an exhilarating ride when you’re in the curl. But every wave breaks, sooner or later.

“Lefty would tell me, ‘Flip, do everything you can to capitalize on this, because it’s not going to last more than a year or two,’” Pallot says. “Then a year or two would go by and he’d say, ‘Think about what’s next, because you can’t have more than a year left.’ So we lived in fear that it was going to go away. And then, as everything does, it did go away.”

Pallot is sanguine about the show’s end. The Walker’s Cay Chronicles aired from 1992 to 2006. “Longer than Seinfeld,” he says, grinning. He cites a number of contributing factors to the cancellation. Television programming became increasingly corporate. Heirs to the Walker’s Cay resort weren’t as committed to the show as the original owner. But basically, Pallot says, philosophically, “things run their course, and the show ran its course. But my God, we went places and did things.”

Photo: William Hereford

Pallot on the bow of his Hell’s Bay skiff.

The show may no longer run, but there’s still a recognizable rhythm to Pallot’s life, an ebb and flow of going places and doing things that suggest little moss has gathered under his feet. He remains a design consultant to Hell’s Bay Boatworks, which has changed ownership. He is still a widely sought speaker and teacher. His ambassador relationships with brands such as Yeti and Costa del Mar keep him in the public eye. And several times a year, Pallot hosts fishing groups in the Bahamas and beyond. Nearly a dozen years after he made his last cast on The Walker’s Cay Chronicles, he seems to have lost little of his relevance to the sport he helped spawn.

“I’m a fifth-generation Floridian,” explains Gray Drummond, who runs a six-thousand-acre hunting and fishing property, Florida Outdoor Experience, where Pallot spends a month each turkey season. “And I’ve always considered Flip Pallot a hero because he was a born-and-raised Florida guy, a modern-day Jeremiah Johnson of Florida, even while he was out there living through his fame.”

Late one afternoon we head from the turkey woods back to Pallot’s campsite. He wants to show me his “mobile man cave,” a seventeen-foot cargo trailer he customized with paneled walls, air-conditioning, and a bed fitted with Spiderman sheets. While on the road, he boasts, “I basically live in a lawn-equipment trailer.” It’s a very Flip Pallot version of a tiny house. We sit in plastic chairs around a folding table, anchored with a bottle of Evan Williams whiskey and a can of bug dope. Dog-day cicadas trill from the live oaks. Pallot swaps knee boots for worn cowboy boots—“ah, like slippers,” he murmurs—and watches a young deer feed nearby.

Photo: William Hereford

Arrows for the hunt.

The cargo trailer affords Pallot something that is as critical to his soul and psyche as a working outboard and room to cast: freedom. Pallot hauls this trailer everywhere. He takes it to the Rocky Mountains each summer for a couple of months. “It’s small and nimble enough to pull into nooks and crannies where there still is incredible fishing.” He pulls it to Texas for deer hunting, to Georgia for deer and hogs and turkeys, and he parks it here in Florida for a chunk of turkey season. You can book a guided trip with Florida Outdoor Experience and never have any idea that Flip Pallot could be your guide.

It’s hardly a reclusive life. One of the challenges of bearing the “living legend” moniker is that you are considered a part of the community commons. There is no shortage of people with their box of Cocoa Puffs in hand, seeking input, advice, counsel. In large measure, Pallot eats it up.

“The sharing part of being known—I can’t call it fame—has been wonderful,” he says. Pallot has mentored dozens of fly-fishing luminaries, among them Rob Fordyce, one of the sport’s best-known guides, and Oliver White, an entrepreneur and owner of bonefish lodges. “It’s been very rewarding,” he says, “to be able to do for others, and to see them take off and live their dreams and live successfully. And by that I don’t necessarily mean financially.”

Photo: William Hereford

Pallot prepares a venison dinner.

Pallot admits that he can feel the pages of the calendar gently falling away, but he’s as adamant now about using modern communication modes as he was when filming The Walker’s Cay Chronicles. One of the more intriguing aspects of his outreach is Pallot’s embrace of social media. Like many of his pursuits, it has the sense of old school and new school coming to easy terms with each other. Prompted by his daughter, Brooke, Pallot signed on to Facebook and Instagram. “And here’s something you might find hard to believe,” he adds. “I get a lot of questions, as you might imagine, and I answer every single one. The natural world is degrading all around us, and it’s not enough to reach people who already know that. Shortly we’re going to turn all this over to a group of people with few touchstones to the natural world, and who don’t understand what it is that we’ve done such a poor job of protecting. I still value the traditional, old-school ways. But I have to cross the bridge. I can’t sit back and simply refuse to embrace a method of reaching the last bastion of hope for saving this stuff.”

The notion of story has been the defining theme of Pallot’s life and career—telling stories, creating stories, nurturing stories while guiding clients. But near the end of our time together, it occurs to me that Pallot has told me very few fishing stories, and only one in any detail. It was about the time he met his wife, Diane.

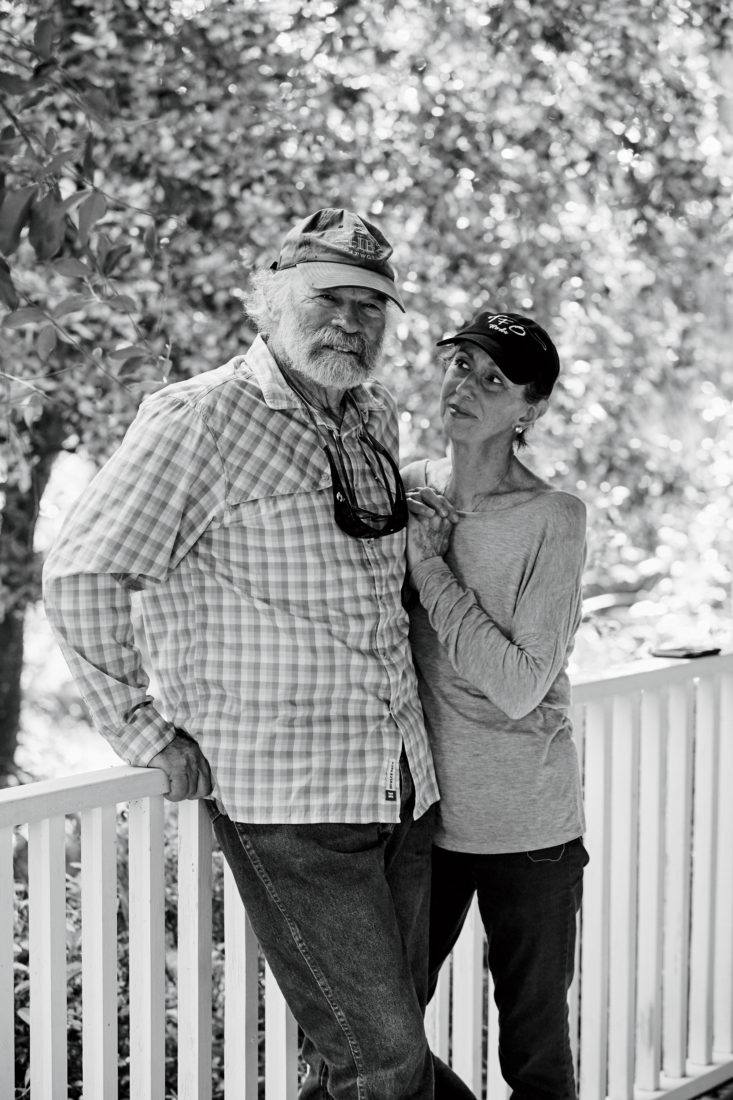

Photo: William Hereford

Flip and Diane at their Florida home.

“We met thirty years ago in Coral Gables, when she hired me as a tarpon guide. She had called another guide, but he never got back with her, so I guess I was her second choice. And right after I guided her, Lefty called me and told me he needed to photograph a pretty girl fishing out of a canoe, and did I know of one? And of course, now I did. And the clearest memory is of a moment when we were on a flat, and I was poling her in a twenty-foot freighter canoe, and Lefty was in another canoe taking pictures, and I remember that I put the bow of the canoe into the breeze, and when the boat turned, I smelled her. And oh, God, it was overwhelming. I was completely in love.”

He is quiet for a moment, and I watch him, in the muted light of a lamp outside his trailer, lips taut, facing the dark, feeling for that wind. He has described Diane as “a magnificent fly fisher” and his near-constant companion on the water, and I ask him if he does that still, turns the boat with Diane in the bow, hoping to catch her scent. He drops his chin to his chest, and gives a little nod as if he is lost forever.

“Of course,” he says. “Of course. Oh, shit, man. I’ve never been the same since.”

On our last morning’s hunt, Pallot and I set up in an island of small trees adrift in a stunning Florida meadow. Palms and live oaks ring the field, and a ground fog swaddles the scene until the sun melts the mist. Pallot is to my right, so I watch the far left end of the field. After a half hour, I slowly swivel my head to the right to find a young tom turkey—a jake—eyeballing us from five feet away.

And he’s not alone. While I was looking the other way, five jakes sauntered up to Pallot, from a slight swale in the field. Pallot never made a sound, never made a move. The turkeys nearly circle the tree where we sit, feeding, scratching, watching, staring. We have no desire to shoot these young birds, so we let them get closer and closer. They are so close, backlit by the sun, that I can see the veins in their blood-red wattles, see their eyeballs rotate in the sockets. The turkeys are in our faces for nearly fifteen minutes, close enough to swat. They are satisfied that there’s nothing out of place here, nothing that doesn’t belong in this fragment of wild, untrammeled Florida.