The baked grits at Birmingham’s Highlands Bar & Grill are so good they make people angry. “One time we briefly took the grits off the menu, and people felt like we had taken their child away from them,” says chef Frank Stitt, who opened Highlands in 1982. “They were irate that we would be so foolhardy.”

Now permanently on the menu as Stone Ground Baked Grits: Benton’s Country Ham, Mushrooms, Thyme, the dish inspires fierce loyalty among regulars, reverence from newbies, and for Stitt, an earnest playfulness. “Highlands might be thought of as this kind of serious restaurant where people get dressed up and have great champagne,” he says. “But then there is this grits soufflé, a way of calming down, using humble ingredients as our stars, and having a little sense of humor.”

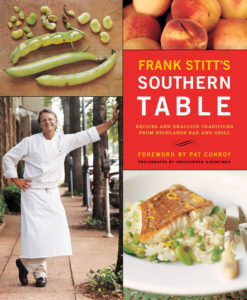

Stitt has received every accolade a chef can hope for, including being named a James Beard Foundation “Who’s Who of Food and Beverage.” But before all the honors, in the early 1980s, he was a young chef hoping to elevate down-to-earth Southern ingredients with the French cooking techniques he had learned from cooking in Europe in the 1970s. Stitt grew up in Cullman, Alabama, and recalls childhood summer lunches of creamed corn, boiled okra, sliced tomatoes, and cornbread from locally milled grain. But by the time he opened Highlands, stale and overly processed corn meal and “instant” grits were the norm. “Ninety-nine percent of commercial grits tasted like bland sawdust,” he says.

This was before “farm-to-table” was a catchphrase, and Stitt was on his own to locate heirloom ingredients. The fledgling chef walked a few blocks from his new restaurant to the Golden Temple health food store, his first source of organic stone-ground grits. (Today, he works with nearby Coosa Valley milling to grind grits to his liking.) Flavorful grits in hand, Stitt tinkered with a French soufflé technique, stirring together cheese, butter, and an egg that helps give the grits literal lift. It’s the same technique he uses today, and it creates a scrumptious fluff. “The grits happen to be a wonderful medium for expressing other Southern ingredients,” he says. “We add a little julienne of country ham, some mushrooms, sherry vinegar, and fresh thyme. It’s a lush combination with the buttery Parmesan.”

From time to time, apprentice chefs have attempted to fuss up the grits with personal flourishes. “We had one young cook who felt they should do their own interpretation, and they started adding garlic. All hell broke loose when I found out,” Stitt says, with a laugh. “That was decades ago, and a few people here still remember and occasionally remind me of how I reacted.”

Some things must never change. Stitt sees it nearly every night at Highlands: As soon as diners sit down to a white tablecloth, someone in the group orders grits for the table. The plate lands, everyone gets a fork, and for a moment, no one is angry about anything.